United States Assay Commission

The United States Assay Commission was an agency of the United States government from 1792 to 1980. Its function was to supervise the annual testing of the gold, silver, and (in its final years) base metal coins produced by the United States Mint to ensure that they met specifications. Although some members were designated by statute, for the most part the commission, which was freshly appointed each year, consisted of prominent Americans, including numismatists. Appointment to the Assay Commission was eagerly sought after, in part because commissioners received a commemorative medal. These medals, different each year, are extremely rare, with the exception of the 1977 issue, which was sold to the general public.

Formerly part of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | April 2, 1792 (authorization) |

| Dissolved | March 14, 1980 |

| Jurisdiction | Testing of gold and silver coin struck by the United States Mint. |

| Annual budget | $2,500 (ended 1980) |

| Parent agency | Department of the Treasury |

The Mint Act of 1792 authorized the Assay Commission. Beginning in 1797, it met in most years at the Philadelphia Mint. Each year, the President of the United States appointed unpaid members, who would gather in Philadelphia to ensure the weight and fineness of silver and gold coins issued the previous year were to specifications. In 1971, the commission met, but for the first time had no gold or silver to test, with the end of silver coinage. Beginning in 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed no members of the public to the commission, and in 1980, he signed legislation abolishing it.

History

Founding and early days (1792–1873)

In January 1791, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton submitted a report to Congress proposing the establishment of a mint. Hamilton concluded his report:

The remedy for errors in the weight and alloy of the coins, must necessarily form a part, in the system of a mint; and the manner of applying it will require to be regulated. The following account is given of the practice in England, in this particular: A certain number of pieces are taken promiscuously out of every fifteen pounds of gold, coined at the Mint, which are deposited, for safe keeping, in a strong box, called the pix [sic, more commonly "pyx"]. This box, from time to time, is opened in the presence of the Lord Chancellor, the officers of the Treasury, and others, and portions are selected from the pieces of each coinage, which are melted together, and the mass assayed by a jury of the Company of Goldsmiths ... The expediency of some similar regulation seems to be manifest.[1]

In response to Hamilton's report, Congress passed the Mint Act of 1792. In addition to setting the standards for the new nation's coinage, Congress provided for an American version of the British Trial of the Pyx:

That from every separate mass of standard gold or silver, which shall be made into coins at the said Mint, there shall be taken, set apart by the Treasurer and reserved in his custody a certain number of pieces, not less than three, and that once in every year the pieces so set apart and reserved, shall be assayed under the inspection of the Chief Justice of the United States, the Secretary and Comptroller of the Treasury, the Secretary for the Department of State, and the Attorney General of the United States, (who are hereby required to attend for that purpose at the said Mint, on the last Monday in July in each year) ... and if it shall be found that the gold and silver so assayed, shall not be inferior to their respective standards herein before declared more than one part in one hundred and forty-four parts, the officer or officers of the said Mint whom it may concern shall be held excusable; but if any greater inferiority shall appear, it shall be certified to the President of the United States, and the said officer or officers shall be deemed disqualified to hold their respective offices.[2]

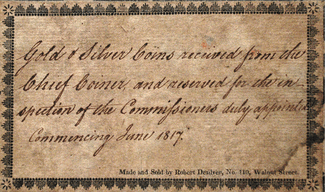

The following January, Congress passed legislation changing the date on which the designated officials met to the second Monday in February. Meetings did not take place immediately; the Mint was not yet striking gold or silver.[3] Minting of silver began in 1794 and gold in 1795, and some coins were saved for assay: the first Mint document mentioning assay pieces is from January 1796 and indicates that exactly $80 in silver had been put aside. The first assay commissioners did not meet until Monday, March 20, 1797, a month later than the prescribed date.[4] Once they did, annual meetings took place each year until 1980, except in 1817 as there had been no gold or silver struck since the last meeting (until 1837, the commission examined the coins since the last testing, rather than for a particular calendar year).[3]

In 1801, the usual meeting was delayed, causing Mint Director Elias Boudinot to complain to President John Adams that depositors were anxious for an audit so the Mint could release coins struck from their bullion. Numismatist Fred Reed suggested that the delay was probably due to poor weather, making it difficult for officials to travel from the new capital of Washington, D.C., to Philadelphia for the assay.[4][5] In response, on March 3, 1801, Congress changed the designation of officials required to attend to "the district judge of Pennsylvania, the attorney for the United States in the district of Pennsylvania, and the commissioner of loans for the State of Pennsylvania".[6] The meeting finally took place on April 27, 1801. The 1806 and 1815 sessions were delayed because of outbreaks of disease in Philadelphia; the one in 1812 was held a month late because of a heavy snowstorm which prevented the commissioners from reaching the Mint.[7] No meeting took place in 1817; a fire had damaged the Philadelphia Mint in January 1816, and no gold or silver awaited the commission.[8] In 1818, Congress substituted the Collector of the Port of Philadelphia for the Pennsylvania loans commissioner as a member of the Assay Commission.[9] With the Coinage Act of 1834, Congress removed the automatic disqualification of Mint officers in the event of an unfavorable assay, leaving the decision to the president.[10]

The Mint Act of 1837 established the Assay Commission in the form it would have for most of the remainder of its existence. It provided that "an annual trial shall be made of the pieces reserved for this purpose [i.e., set aside for the assay] at the Mint and its branches, before the judge of the district court of the United States, for the eastern district of Pennsylvania, the attorney of the United States, for the eastern district of Pennsylvania, and the collector of the port of Philadelphia, and such other persons as the President shall, from time to time, designate for that purpose, who shall meet as commissioners, for the performance of this duty, on the second Monday in February, annually".[11] The usual procedure for members of the public to be named to the commission after public appointments began was for the Mint Director to send the president a list of candidates for his approval.[3] According to Jesse P. Watson in his monograph on the Bureau of the Mint, the admission of members of the public to the Assay Commission meant "that permanency and high official dignity were no longer characteristic of the commission".[12]

In 1861, as the American Civil War broke out, North Carolina joined the Confederate States. The Charlotte Mint, taken over by the Confederacy, eventually closed as the dies that had been shipped from the Philadelphia Mint wore out, and it could obtain no more. Nevertheless, 12 half eagles ($5 gold coins) were sent from Charlotte to Philadelphia, through enemy lines, in October 1861. They were duly tested by the 1862 Assay Commission, and were found to be correct.[13]

In 1864, with the metal nickel, used in the cent in short supply, Mint Director James Pollock asked that year's commission to opine on a substitute for the copper-nickel used in the cent. The members endorsed French bronze (95% copper and 5% tin or zinc) as a metal to be used in the cent and a proposed two-cent piece.[14] Pollock sent the conclusions to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, who forwarded them (and draft legislation) to Maine Senator William P. Fessenden, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.[15] The Coinage Act of 1864 was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on April 22, 1864.[16]

Later years (1873–1949)

The Coinage Act of 1873 revised the laws relating to coinage and the Mint and retired several denominations including the two-cent piece.[17] The act also changed the officers required to serve on the Assay Commission:

That to secure a due conformity in the gold and silver coins to their respective standards of fineness and weight, the judge of the district court of the United States for the eastern district of Pennsylvania, the Comptroller of the Currency, the assayer of the assay-office at New York, and such other persons as the President shall, from time to time, designate, shall meet as assay-commissioners, at the mint in Philadelphia, to examine and test, in the presence of the Director of the Mint, the fineness and weight of the coins reserved by the several mints for this purpose, on the second Wednesday in February, annually.[18]

The act also required the Mint to put aside one of every thousand gold coins struck, and one of every two thousand silver coins for the assay. It provided the procedure for putting the coins aside, sealing them in envelopes, and placing them in a pyx to be opened by the assay commissioners.[19]

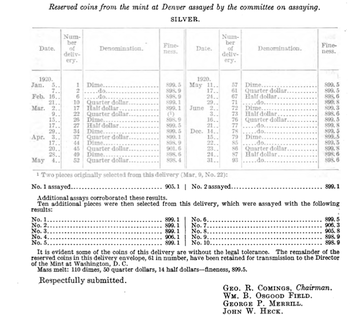

The 1881 Assay Commission found that approximately 3,000 silver dollars struck at the Carson City Mint (1881-CC) had been struck in .892 silver rather than the legally mandated .900. It is unclear if the Treasury took any steps to attempt to recover the issued pieces. The 1885 commission detected a single silver dollar which was 1.51 grains (0.098 g) below specifications, the permitted tolerance being 1.50 grains (0.097 g).[20] In 1921, the Assay Commission found that some coins struck at the Denver Mint were struck in .905 or .906 silver, above the legal .900 by more than the permitted tolerance. Investigation found that ingots which had been rejected and were intended for melting had instead been used for coin.[21] In the early 20th century, the San Francisco Mint struck silver coins for the Philippines, then a US possession; those pieces were included in the assay.[22] Proof coins struck by the Mint for collectors were included in the assay; pieces struck under contract with foreign governments were not.[23]

The pyx was a rosewood box, 3 feet (0.91 m) square, of European work, and sealed by heavy padlocks. It was not filled by the coins put aside for the 1934 Assay Commission, of which there were 759 with a total face value of $12,050.[24][25] This had increased by 1940 to 79,847 coins, all silver as gold coins were no longer being struck,[26] and by 1941, many reserved coins could not be kept in the pyx, instead being placed in packing boxes, overflowing with sealed envelopes.[23] By the late 1940s, more than ten million coins were being struck each day at Philadelphia alone;[27] in 1947, Congress reduced the number of silver coins required to be put aside for assay from one in 2,000 to one in 10,000.[28] This was done at the urging of the Department of the Treasury, as having to store so many assay coins was a burden to the Mint, and it felt that the number of coins available to the commission would still be sufficient.[29]

Final years and abolition (1950–1980)

By the 1950s, there was considerable competition among numismatists to be appointed an assay commissioner. Appointees received no compensation, but the appointment was prestigious and carried with it a prized assay medal. The procedure was changed so that the Mint Director submitted the names of more individuals than would actually be appointed to the White House, where the final choices were made. It remained possible for the director to ask for special consideration for certain individuals.[3] Later nominations were also screened by the Federal Bureau of Investigation[30] and by the IRS. The Mint Director received nominations for assay commissioner from legislators, political organizations, government officials, and from members of the public.[31]

In 1971, for the first time, the Assay Commission had no silver coins to test; none were struck by the Mint for circulation in 1970.[20] Although part-silver Kennedy half dollars were struck in 1970, they were only for collectors and were not put aside for assay. Commissioners could instead test 21,975 dimes and 11,098 quarters, all made from copper-nickel clad,[24] though as the Associated Press, reporting on the 1973 Assay Commission, put it, "a discovery of a bum coin hasn't occurred in years."[32] Only one in every 100,000 clad or silver-clad pieces was put aside for the Assay Commission, and only one in every 200,000 dimes.[33] At the 1974 meeting, one copper-nickel Eisenhower dollar was discovered which weighed 15 grains (0.97 g) below specification; after reference to the rules, the coin was deemed barely within guidelines. Numismatist Charles Logan, in his 1979 article about the impending end of the Assay Commission, stated that this incident pointed out "the basic problem with the annual trial. First, the members were not exactly sure how their job was done, or what the requirements were. Second, they really did not want to report a fault in the coinage. Finally, even if the one dollar coin had been found faulty, [it would have had] little consequence, except to prompt greater vigilance at the Mint."[34]

In early 1977, outgoing Mint Director Mary Brooks sent a list of 117 nominees to the new president, Jimmy Carter, from which it was expected that about two or three dozen names would be selected. Carter refused to make any public appointments, feeling the Assay Commission was unneeded given that the Mint performed the same work through routine internal checks and that the $2,500 appropriated each year was a poor use of taxpayer money. Only government members served on the Assay Commission in 1977–1980.[34][35] Even so, hundreds of numismatists applied to be on the 1978 commission. Carter made no appointments that year; the only members were those designated by statute.[36]

The 1979 meeting, attended by the government-employed commission members and Mint Director Stella Hackel Sims, was held eight days late on February 22 due to schedule conflicts.[34] In June 1979, Carter's Presidential Reorganization Project recommended the abolition of the Assay Commission and two other small agencies. The report estimated that having an Assay Commission cost the federal government about $20,000 and that the work was done better by vending machine manufacturers to avoid having their machines jam.[37] In August, columnist Jack Anderson deemed the commission an example of wasteful spending in Washington, characterizing its activities, "more than a decade ago, the government stopped putting either gold or silver in its coins—but the commission continues to hold its annual luncheon meeting. Solemnly, the commissioners measure the amounts of nonprecious metals in U.S. coins, and strike a medal to commemorate their activities. This useless exercise costs the taxpayers about $20,000 a year."[38] As coin collector and columnist Gary Palmer put it in 1979, "who really cares if the weight of a cupro-nickel quarter is off by a grain or two?"[39]

On March 14, 1980, Carter approved legislation abolishing the Assay Commission, as well as the other two agencies, as recommended by his Reorganization Project. The President wrote in a signing statement that with the end of gold and silver coinage, the need for the commission had diminished.[40] Numismatic leaders objected to the ending of the commission, considering the expense small and the tradition worth keeping, although they concurred the commission "had become an anachronism".[41] At the time of its abolition, the Assay Commission was the oldest existing government commission. In 2000 and 2001, New Jersey Congressman Steven Rothman introduced legislation to revive the Assay Commission, stating that re-establishing the commission would assure public confidence in the gold, silver, and platinum bullion coins struck by the Mint. The bills died in committee.[35][42]

Functions and activities

The general function of the Assay Commission was to examine the gold and silver coins of the Mint and ensure they met the proper specifications.[43] Assay commissioners were placed on one of three committees in most years: the Counting, Weighing, and Assaying Committees. The Counting Committee verified that the number of each type of coin in packets selected from the pyx matched what Mint records said should be there. The Weighing Committee measured the weight of coins from the pyx, checking them against the weight required by law. The Assaying Committee worked with the Philadelphia Mint's assayer as he measured the precious metal content of some of the coins.[44] In some years there was a Committee on Resolutions—in 1912, it urged that a leaflet be published for visitors to the Mint's coin collection, and that a medal be struck to commemorate the collection. The full Assay Commission adopted that committee's report.[45]

Congress in 1828 had required that the weights kept by the Mint Director be tested for accuracy in the presence of the assay commissioners each year.[46] By statute passed in 1911, the commission was required to inspect the weights and balances used in assaying at the Philadelphia Mint, and to report on their accuracy.[47] This included the government's official standard pound weight that had been brought from the United Kingdom.[20][48]

According to a description of the 1948 meeting, silver coins selected for assay were first placed between steel rollers until the thickness was reduced to .0001 inches (0.0025 mm), and then were chopped into fine pieces and dissolved in nitric acid. The fineness of the silver in the coin could be determined by the amount of salt solution needed to precipitate all the silver in the liquid.[27] Numismatist Francis Pessolano-Filos described the work of the Assay Commission:

Using balances and weights, the commission weighed several examples of each type of coin, then used calipers to examine them for proper thickness, and finally, using various acids and solvents, determined the amount of alloy used in manufacture of the planchets. Ledgers and journal books on the mint were also examined. If there were any imperfections or deviations from the legal standards in the coins examined, the information was immediately sent to the president of the United States.[49]

The commission operated under rules first adopted by the 1856 commission, and then passed down, year to year, and amendable by any Assay Commission, although in practice little change was made.[48] Under the rules, the Director of the Mint called the assay commissioners to order, then introduced the federal judge who was an ex officio member, who presided over the meetings; if the judge was absent, the members elected a chairman. The chairman divided the members into the committees. If there had been a change of officers at a mint, commissioners examined coins from before and after. After the committees completed their work, the members re-assembled to report their findings and to vote on their report.[50]

Every Assay Commission passed the coinage that it was called upon to examine.[4] If pieces varying from the standard were found, that was also noted; the 1885 Assay Commission reported the one substandard silver coin, which came from the Carson City Mint, but urged the president to take no action, noting that the coin was underweight by an amount too small to be measured by the scales at Carson City.[20]

Remains of coins used in the assay were melted by the Mint; those put aside for the Assay Commission that were not used were placed in circulation from Philadelphia, and were not marked or distinguished in any way.[35] There were thousands of coins for the commission, of which only a few were assayed. Commissioners often purchased some of the remaining pieces as souvenirs, although commemorative coins could not be purchased if Congress had given the exclusive right to sell them to a sponsoring organization—they were instead destroyed.[44]

Commissioners

Appointments of members of the public to the Assay Commission by the president are known to have been made as early as 1841;[51] the final ones were made in 1976.[35] Many early commissioners were chosen for their scientific or intellectual attainments. Such qualifications were not required of later public appointees, who included such prominent figures as Ellin Berlin, wife of songwriter Irving Berlin.[30] The first women to be appointed to the Assay Commission were Mrs. Kellogg Fairbanks of Chicago and Mrs. B.B. Munford of Richmond, Virginia, both in 1920.[52]

The recordholder for service as a commissioner is Herbert Gray Torrey, 36 times an assay commissioner between 1874 and 1910 (missing only 1879) by virtue of his office as assayer of the New York Assay Office. The recordholder as a presidential appointee is Dr. James Lewis Howe, head of the Department of Chemistry at Washington and Lee University, 18 times an assay commissioner, serving in 1907 and then each year from 1910 to 1926.[53] An employee of the National Bureau of Standards was included in the presidential appointments each year;[3] he brought with him the weights used in the assay, which were checked by the agency in advance.[43] Although no future president served as an assay commissioner,[lower-alpha 1] Comptroller of the Currency Charles G. Dawes was a commissioner in 1899 and 1900; he was Vice President of the United States from 1925 to 1929.[53][54]

Among those appointed was coin collector and Congressman William A. Ashbrook, 14 times an assay commissioner between 1908 and 1934.[53] Ashbrook's presence on the 1934 Assay Commission has led to speculation that he might have used his position as an assay commissioner (he left Congress in 1921) to secure one or more 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagles, almost all of which were melted due to the end of gold coinage for circulation. Assay commissioners were traditionally allowed to purchase coins from the pyx that were not assayed, and numismatic historian Roger Burdette speculates that Ashbrook, generally well-treated by the Treasury Department due to his onetime congressional position, might have exchanged other gold pieces for the 1933 coins.[55]

The three known specimens of the 1873-CC quarter, without arrows by the date, and the only known dime of that description, may have been salvaged from assay pieces, as the remainder of those coins had been ordered melted as underweight.[13] A similar mystery attends the 1894 Barber dime struck at San Francisco (1894-S) of which the published mintage is 24, although it is not certain whether this total includes the one sent to Philadelphia to await the 1895 Assay Commission. The fact that one of the 1895 assay commissioners was Robert Barnett, chief clerk of the San Francisco Mint, has led numismatic writers Nancy Oliver and Richard Kelly to speculate that he may have been made an assay commissioner in order to retrieve the dime. The 1895 Assay Commission report confirms that the dime was there, as it was counted by the Counting Committee. The dime is not mentioned as having been either weighed or assayed; Oliver and Kelly, in a May 2011 article in The Numismatist, suggest that Barnett used that privilege of assay commissioners to obtain the rarity. He is not known, however, to have written or spoken of the matter before his murder in 1904.[56]

In 1964, former assay commissioners formed the Old Time Assay Commissioners Society (OTACS). When President Carter stopped appointing public members to the commission in 1977, the OTACS fundraised in an unsuccessful attempt to induce the government to continue that tradition. The society met annually through 2012, usually at the site of the yearly convention of the American Numismatic Association (ANA).[31][57] With the number of surviving OTACS members at less than three dozen, the society plans no further meetings; its 2012 session in conjunction with the ANA convention in Philadelphia included an event at the mint.[58]

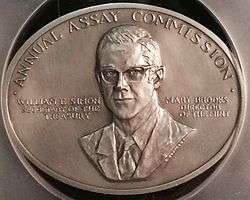

Medals

Assay Commission medals were struck from a variety of metals, including copper, silver, bronze, and pewter. The first Assay Commission medals were struck in 1860 at the direction of Mint Director James Ross Snowden. The initial purpose in having medals struck was not principally to provide keepsakes to the assay commissioners, but to advertise the Mint's medal-striking capabilities. The nascent custom lapsed when Snowden left office in 1861.[59]

Numismatists R.W. Julian and Ernest E. Keusch, in their work on Assay Commission medals, theorize that the resumption of Assay Commission medal striking in 1867 was at the request of Mint Engraver James B. Longacre to new Mint Director William Millward.[60] Medals to be given to assay commissioners were struck each year after that until public members ceased to be appointed to the Assay Commission in 1977.[61]

Early assay medals featured on the obverse a bust of Liberty or figure of Columbia, and on the reverse a wreath surrounding the words "annual assay" and the year.[62] The 1870 obverse, by Longacre's successor William Barber, features Moneta surrounded by implements of the assay, such as scales and the pyx.[63] The distinctive designs for each year would sometimes be topical—the 1876 medal bears a design for the centennial of American Independence, and 1879's depicted the recently deceased Mint Director Henry Linderman. Beginning in 1880, they most often featured the president or Treasury Secretary. The medals in 1901 and from 1903 to 1909 were rectangular, a style popular at the time.[64] The 1920 reverse, by Engraver George T. Morgan, had a design which symbolized the ending of World War I; in 1921, an extra medal was struck in gold, given by the assay commissioners to outgoing President Woodrow Wilson as a mark of respect.[65]

The 1936 issuance was a mule of the Mint's medals for the president at the time, Franklin Roosevelt, and the first president, George Washington. Bearing the words, "annual assay 1936" on the edge, the medal was prepared in this manner by order of Mint Director Nellie Tayloe Ross[66] after Mint officials realized that they had forgotten to prepare a special design for an assay medal.[67] The 1950 medal illustrates a meeting of three 1792 officeholders (Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Jay). Although they were officeholders designated by the Mint Act of 1792, no assay took place until 1797, by which time all three had left those offices.[68] There was no specially designed medal in 1954; instead, the assay commissioners, who met in Philadelphia on Lincoln's Birthday, February 12, 1954, chose to receive the Mint's standard presidential medal depicting Abraham Lincoln, with the commissioner's name on the edge.[69] The final medals, 1976 and 1977, were oval and of pewter. The 1977 medal, depicting Martha Washington, was not needed for presentation, as no public assay commissioners were appointed.[70] They were presented to various Mint and other Treasury officials, and when there was public objection, more were struck and were placed on sale for $20 at the mints and other Treasury outlets in 1978. Material was available for about 1,500 medals, and they were initially not available by mail.[71] They were still available in person, and by mail order, in 1980.[41]

All Assay Commission medals are extremely rare. Except for the 1977 medal, none is believed to have been issued in a quantity of greater than 200, and in most years fewer than 50 were struck.[61] Additional copies of several 19th-century issues are known to have been illicitly struck; the Mint ended such practices in the early 20th century. The obverse of the 1909 issue, depicting Treasury Secretary George Cortelyou, was reused as Cortelyou's entry in the Mint's series of medals honoring Secretaries of the Treasury. The later pieces were struck with a blank reverse, but in the early 1960s, the reverse design from the Assay Commission issue was used with the Cortelyou obverse, and an unknown number sold to the public. The restrikes are said to be less distinctly struck than the originals.[72]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Assay Commission. |

Explanatory notes

- Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, later president, was one of the officials designated as assay commissioners by the 1792 act, but left office in 1793, before the first meeting took place.

Citations

- Preston & Eckels, p. 67.

- Bureau of the Mint, pp. 9–10.

- Julian & Keusch, p. 3.

- R. W. Julian, "The United States Annual Assay Commission: 1797 to 1817". Article included in this DVD set of Assay Commission records: Burdette, Roger. Annual Assay Commission – United States Mint 1800–1943. Great Falls, Va.: Seneca Mill Press. ISBN 978-0-9768986-3-4.

- Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 268.

- Bureau of the Mint, p. 16.

- Pessolano-Filos, p. 273.

- Coin World Almanac 1977, pp. 268–269.

- Bureau of the Mint, p. 20.

- Bureau of the Mint, p. 26.

- Bureau of the Mint, p. 35.

- Watson, p. 5.

- DeLorey, Thomas (August 1996). "The Trial of the Pyx". CoinAge. 1 (17): 64–65, 68, 70. Bibcode:1870Natur...1R.429.. doi:10.1038/001429b0.

- Carothers, pp. 196–197.

- Taxay, p. 240.

- Taxay, p. 242.

- Taxay, pp. 249, 258.

- Bureau of the Mint, p. 61.

- Bureau of the Mint, p. 59.

- Herbert, Alan (September 13, 2011). "Defunct Assay Commission used to check US coins". numismaster.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- Mellon, Andrew W. (1922). Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury, 1922. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. p. 631.

- Roberts, p. 59.

- "The Assay Commission for 1941". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, Co.: American Numismatic Association: 256–257. April 1941.

- "Assay meet". Coins. Iola, Wis.: Krause Publications: 20–21. May 1971.

- "Assay Commission meets in Philadelphia". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, Co.: American Numismatic Association: 183. March 1934.

- "Annual Assay Commission meets". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, Co.: American Numismatic Association: 87–88. February 1941.

- Abbott, H.M. (April 1948). "Notes on the Assay Commission". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, Co.: American Numismatic Association: 268–269.

- United States Statutes at Large. 61. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1948. p. 129.

- Senate Committee on Banking and Currency (February 28, 1947). Trial Pieces of Coins, Senate report No. 39, 80th Congress, 1st session. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 1–2.

- Pessolano-Filos, p. xiv.

- Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 247.

- "Coins checked, no clunkers". AP via Reading Eagle. February 15, 1973. p. 18.

- United States Mint, p. 15.

- Logan, Charles (May 1979). "The last 'Trial of the Pyx'". CoinAge. Encino, Calif.: Behn-Miller Publishers, Inc.: 58–59.

- Coin World Almanac 2011, p. 164.

- "Assay Commission: Last gasp?". Coins: 22. May 1978.

- "Administration finally comes up with victims". AP via The Argus-Press. June 4, 1979. p. 2.

- Anderson, Jack (August 20, 1979). "Defense Secretary Brown may have to defend self". The Robesonian. p. 6.

- Palmer, Gary L. (January 14, 1979). "Assay Commission meeting abolished". Copley News Service via The Evening News. p. 5B.

- Public Papers of the Presidents. 1980 Volume 1. United States Government Printing Office. 1981. p. 483.

- Reiter, Ed (November 16, 1980). "A Mint tradition is continued" (PDF). The New York Times. pp. 32, 38. (subscription required)

- Gilkes, Paul (June 7, 2010). "1976 last year for Assay Commission public participation". Coin World. pp. 94–95.

- Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 246.

- Roger W. Burdette, "Introduction and purpose" article included in this DVD set of Assay Commission records: Burdette, Roger. Annual Assay Commission – United States Mint 1800–1943. Great Falls, Va.: Seneca Mill Press. ISBN 978-0-9768986-3-4.

- Roberts, pp. 60–61.

- Bureau of the Mint, p. 24.

- Watson, p. 31.

- United States Mint, pp. 18–19.

- Pessolano-Filos, p. xiii.

- United States Mint, pp. 9–12.

- Pessolano-Filos, p. 131.

- "Women member of Assay Commission". The Evening Independent. March 26, 1920. p. 2.

- Coin World Almanac 1977, pp. 248–268.

- "Charles Dawes". United States Senate. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- Burdette, Roger (August 3, 2009). "Lifting the veils from the 1933 double eagle". Coin World. pp. 1, 104.

- Oliver, Nancy; Kelly, Richard (May 2011). "The 1894-S dime". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, Co.: American Numismatic Association: 99–100.

- "ANA convention update". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, Co.: American Numismatic Association: 81. June 2012.

- Ganz, David (July 23, 2012). "Final OTACS meeting set for Philly". numismaster.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Julian & Keusch, pp. 3, 9.

- Julian & Keusch, p. 10.

- Julian & Keusch, pp. 6–7.

- Julian & Keusch, pp. 10–11.

- Julian & Keusch, p. 12.

- Julian & Keusch, pp. 3–4.

- Julian & Keusch, pp. 4, 42–43.

- Pessolano-Filos, p. 81.

- Julian & Keusch, p. 4.

- Julian & Keusch, p. 66.

- Pessolano-Filos, p. 100.

- Julian & Keusch, pp. 86–87.

- "Assay medals: Own your own". Coins: 22. May 1978.

- Julian & Keusch, pp. 3–4, 53.

Bibliography

- Bureau of the Mint (1904). Laws of the United States Relating to the Coinage. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- Carothers, Neil (1930). Fractional Money: A History of Small Coins and Fractional Paper Currency of the United States. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (reprinted 1988 by Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc., Wolfeboro, NH). ISBN 0-943161-12-6.

- Coin World Almanac (3rd ed.). Sidney, Ohio: Amos Press. 1977. ASIN B004AB7C9M.

- Coin World Almanac (8th ed.). Sidney, Ohio: Amos Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-944945-60-5.

- Julian, R. W.; Keusch, Ernest E. (October 1989). "Medals of the United States Assay Commission 1860–1977". Token and Medal Society Journal. 29 (5(2)).

- Pessolano-Filos, Francis (1983). Margaret M. Walsh (ed.). The Assay Medals and the Assay Commissions, 1841–1977. New York: Eros Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-911571-01-1.

- Preston, Robert E.; Eckels, James Herron (1896). History of the Monetary Legislation and of the Currency System of the United States. Philadelphia: John J. McVey.

- Roberts, George E. (1913). Report of the Director of the Mint, 1912. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- Taxay, Don (1983). The U.S. Mint and Coinage (reprint of 1966 ed.). New York: Sanford J. Durst Numismatic Publications. ISBN 978-0-915262-68-7.

- United States Mint (1976). The Bicentennial Assay Commission. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- Watson, Jesse P. (1926). The Bureau of the Mint: Its History, Activities and Organization. Service Monographs of the United States Government, No. 37. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.