Disjoint-set data structure

In computer science, a disjoint-set data structure (also called a union–find data structure or merge–find set) is a data structure that tracks a set of elements partitioned into a number of disjoint (non-overlapping) subsets. It provides near-constant-time operations (bounded by the inverse Ackermann function) to add new sets, to merge existing sets, and to determine whether elements are in the same set. In addition to many other uses (see § Applications), disjoint-sets play a key role in Kruskal's algorithm for finding the minimum spanning tree of a graph.

| Disjoint-set/Union-find Forest | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | multiway tree | ||||||||||||||||

| Invented | 1964 | ||||||||||||||||

| Invented by | Bernard A. Galler and Michael J. Fischer | ||||||||||||||||

| Time complexity in big O notation | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

History

Disjoint-set forests were first described by Bernard A. Galler and Michael J. Fischer in 1964.[2] In 1973, their time complexity was bounded to , the iterated logarithm of , by Hopcroft and Ullman.[3] (A proof is available here.) In 1975, Robert Tarjan was the first to prove the (inverse Ackermann function) upper bound on the algorithm's time complexity,[4] and, in 1979, showed that this was the lower bound for a restricted case.[5] In 1989, Fredman and Saks showed that (amortized) words must be accessed by any disjoint-set data structure per operation,[6] thereby proving the optimality of the data structure.

In 1991, Galil and Italiano published a survey of data structures for disjoint-sets.[7]

In 1994, Richard J. Anderson and Heather Woll described a parallelized version of Union–Find that never needs to block.[8]

In 2007, Sylvain Conchon and Jean-Christophe Filliâtre developed a persistent version of the disjoint-set forest data structure, allowing previous versions of the structure to be efficiently retained, and formalized its correctness using the proof assistant Coq.[9] However, the implementation is only asymptotic if used ephemerally or if the same version of the structure is repeatedly used with limited backtracking.

Representation

A disjoint-set forest consists of a number of elements each of which stores an id, a parent pointer, and, in efficient algorithms, either a size or a "rank" value.

The parent pointers of elements are arranged to form one or more trees, each representing a set. If an element's parent pointer points to no other element, then the element is the root of a tree and is the representative member of its set. A set may consist of only a single element. However, if the element has a parent, the element is part of whatever set is identified by following the chain of parents upwards until a representative element (one without a parent) is reached at the root of the tree.

Forests can be represented compactly in memory as arrays in which parents are indicated by their array index.

Operations

MakeSet

The MakeSet operation makes a new set by creating a new element with a unique id, a rank of 0, and a parent pointer to itself. The parent pointer to itself indicates that the element is the representative member of its own set.

The MakeSet operation has time complexity, so initializing n sets has time complexity.

Pseudocode:

function MakeSet(x) is

if x is not already present then

add x to the disjoint-set tree

x.parent := x

x.rank := 0

x.size := 1

Find

Find(x) follows the chain of parent pointers from x up the tree until it reaches a root element, whose parent is itself. This root element is the representative member of the set to which x belongs, and may be x itself.

Path compression

Path compression flattens the structure of the tree by making every node point to the root whenever Find is used on it. This is valid, since each element visited on the way to a root is part of the same set. The resulting flatter tree speeds up future operations not only on these elements, but also on those referencing them.

Tarjan and Van Leeuwen also developed one-pass Find algorithms that are more efficient in practice while retaining the same worst-case complexity: path splitting and path halving.[4]

Path halving

Path halving makes every other node on the path point to its grandparent.

Path splitting

Path splitting makes every node on the path point to its grandparent.

Pseudocode

| Path compression | Path halving | Path splitting |

|---|---|---|

function Find(x)

if x.parent ≠ x

x.parent := Find(x.parent)

return x.parent |

function Find(x)

while x.parent ≠ x

x.parent := x.parent.parent

x := x.parent

return x |

function Find(x)

while x.parent ≠ x

x, x.parent := x.parent, x.parent.parent

return x |

Path compression can be implemented using iteration by first finding the root then updating the parents:

function Find(x) is

root := x

while root.parent ≠ root

root := root.parent

while x.parent ≠ root

parent := x.parent

x.parent := root

x := parent

return root

Path splitting can be represented without multiple assignment (where the right hand side is evaluated first):

function Find(x)

while x.parent ≠ x

next := x.parent

x.parent := next.parent

x := next

return x

or

function Find(x)

while x.parent ≠ x

prev := x

x := x.parent

prev.parent := x.parent

return x

Union

Union(x,y) uses Find to determine the roots of the trees x and y belong to. If the roots are distinct, the trees are combined by attaching the root of one to the root of the other. If this is done naively, such as by always making x a child of y, the height of the trees can grow as . To prevent this union by rank or union by size is used.

by rank

Union by rank always attaches the shorter tree to the root of the taller tree. Thus, the resulting tree is no taller than the originals unless they were of equal height, in which case the resulting tree is taller by one node.

To implement union by rank, each element is associated with a rank. Initially a set has one element and a rank of zero. If two sets are unioned and have the same rank, the resulting set's rank is one larger; otherwise, if two sets are unioned and have different ranks, the resulting set's rank is the larger of the two. Ranks are used instead of height or depth because path compression will change the trees' heights over time.

by size

Union by size always attaches the tree with fewer elements to the root of the tree having more elements.

Pseudocode

| Union by rank | Union by size |

|---|---|

function Union(x, y) is

xRoot := Find(x)

yRoot := Find(y)

if xRoot = yRoot then

// x and y are already in the same set

return

// x and y are not in same set, so we merge them

if xRoot.rank < yRoot.rank then

xRoot, yRoot := yRoot, xRoot // swap xRoot and yRoot

// merge yRoot into xRoot

yRoot.parent := xRoot

if xRoot.rank = yRoot.rank then

xRoot.rank := xRoot.rank + 1 |

function Union(x, y) is

xRoot := Find(x)

yRoot := Find(y)

if xRoot = yRoot then

// x and y are already in the same set

return

// x and y are not in same set, so we merge them

if xRoot.size < yRoot.size then

xRoot, yRoot := yRoot, xRoot // swap xRoot and yRoot

// merge yRoot into xRoot

yRoot.parent := xRoot

xRoot.size := xRoot.size + yRoot.size |

Time complexity

Without path compression (or a variant), union by rank, or union by size, the height of trees can grow unchecked as , implying that Find and Union operations will take time.

Using path compression alone gives a worst-case running time of ,[10] for a sequence of n MakeSet operations (and hence at most Union operations) and f Find operations.

Using union by rank alone gives a running-time of (tight bound) for m operations of any sort of which n are MakeSet operations.[10]

Using both path compression, splitting, or halving and union by rank or size ensures that the amortized time per operation is only [4][5] for m disjoint-set operations on n elements, which is optimal,[6] where is the inverse Ackermann function. This function has a value for any value of n that can be written in this physical universe, so the disjoint-set operations take place in essentially constant time.

Proof of O(log*(n)) time complexity of Union-Find

Proof of O(log*n) amortized time [11] of Union Find[12][13][14]

Statement: If m operations, either Union or Find, are applied to n elements, the total run time is O(m log*n), where log* is the iterated logarithm.

Lemma 1: As the find function follows the path along to the root, the rank of node it encounters is increasing.

- Proof: claim that as Find and Union operations are applied to the data set, this fact remains true over time. Initially when each node is the root of its own tree, it's trivially true. The only case when the rank of a node might be changed is when the Union by Rank operation is applied. In this case, a tree with smaller rank will be attached to a tree with greater rank, rather than vice versa. And during the find operation, all nodes visited along the path will be attached to the root, which has larger rank than its children, so this operation won't change this fact either.

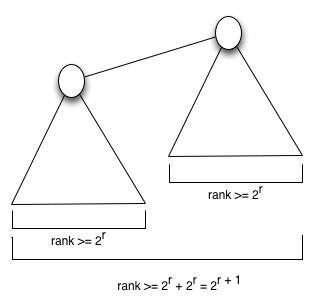

Lemma 2: A node u which is root of a subtree with rank r has at least 2r nodes.

- Proof: Initially when each node is the root of its own tree, it's trivially true. Assume that a node u with rank r has at least 2r nodes. Then when two trees with rank r Union by Rank and form a tree with rank r + 1, the new node has at least 2r + 2r = 2r + 1 nodes.

Lemma 3: The maximum number of nodes of rank r is at most n/2r.

- Proof: From lemma 2, we know that a node u which is root of a subtree with rank r has at least 2r nodes. We will get the maximum number of nodes of rank r when each node with rank r is the root of a tree that has exactly 2r nodes. In this case, the number of nodes of rank r is n/2r

For convenience, we define "bucket" here: a bucket is a set that contains vertices with particular ranks.

We create some buckets and put vertices into the buckets according to their ranks inductively. That is, vertices with rank 0 go into the zeroth bucket, vertices with rank 1 go into the first bucket, vertices with ranks 2 and 3 go into the second bucket. If the Bth bucket contains vertices with ranks from interval [r, 2r − 1] = [r, R - 1] then the (B+1)st bucket will contain vertices with ranks from interval [R, 2R − 1].

_Union_Find.jpg)

We can make two observations about the buckets.

- The total number of buckets is at most log*n

- Proof: When we go from one bucket to the next, we add one more two to the power, that is, the next bucket to [B, 2B − 1] will be [2B, 22B − 1]

- The maximum number of elements in bucket [B, 2B – 1] is at most 2n/2B

- Proof: The maximum number of elements in bucket [B, 2B – 1] is at most n/2B + n/2B+1 + n/2B+2 + … + n/22B – 1 ≤ 2n/2B

Let F represent the list of "find" operations performed, and let

Then the total cost of m finds is T = T1 + T2 + T3

Since each find operation makes exactly one traversal that leads to a root, we have T1 = O(m).

Also, from the bound above on the number of buckets, we have T2 = O(mlog*n).

For T3, suppose we are traversing an edge from u to v, where u and v have rank in the bucket [B, 2B − 1] and v is not the root (at the time of this traversing, otherwise the traversal would be accounted for in T1). Fix u and consider the sequence v1,v2,...,vk that take the role of v in different find operations. Because of path compression and not accounting for the edge to a root, this sequence contains only different nodes and because of Lemma 1 we know that the ranks of the nodes in this sequence are strictly increasing. By both of the nodes being in the bucket we can conclude that the length k of the sequence (the number of times node u is attached to a different root in the same bucket) is at most the number of ranks in the buckets B, i.e. at most 2B − 1 − B < 2B.

Therefore,

From Observations 1 and 2, we can conclude that

Therefore, T = T1 + T2 + T3 = O(m log*n).

Applications

Disjoint-set data structures model the partitioning of a set, for example to keep track of the connected components of an undirected graph. This model can then be used to determine whether two vertices belong to the same component, or whether adding an edge between them would result in a cycle. The Union–Find algorithm is used in high-performance implementations of unification.[15]

This data structure is used by the Boost Graph Library to implement its Incremental Connected Components functionality. It is also a key component in implementing Kruskal's algorithm to find the minimum spanning tree of a graph.

Note that the implementation as disjoint-set forests doesn't allow the deletion of edges, even without path compression or the rank heuristic.

Sharir and Agarwal report connections between the worst-case behavior of disjoint-sets and the length of Davenport–Schinzel sequences, a combinatorial structure from computational geometry.[16]

See also

- Partition refinement, a different data structure for maintaining disjoint sets, with updates that split sets apart rather than merging them together

- Dynamic connectivity

References

- Tarjan, Robert Endre (1975). "Efficiency of a Good But Not Linear Set Union Algorithm". Journal of the ACM. 22 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1145/321879.321884. hdl:1813/5942.

- Galler, Bernard A.; Fischer, Michael J. (May 1964). "An improved equivalence algorithm". Communications of the ACM. 7 (5): 301–303. doi:10.1145/364099.364331.. The paper originating disjoint-set forests.

- Hopcroft, J. E.; Ullman, J. D. (1973). "Set Merging Algorithms". SIAM Journal on Computing. 2 (4): 294–303. doi:10.1137/0202024.

- Tarjan, Robert E.; van Leeuwen, Jan (1984). "Worst-case analysis of set union algorithms". Journal of the ACM. 31 (2): 245–281. doi:10.1145/62.2160.

- Tarjan, Robert Endre (1979). "A class of algorithms which require non-linear time to maintain disjoint sets". Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 18 (2): 110–127. doi:10.1016/0022-0000(79)90042-4.

- Fredman, M.; Saks, M. (May 1989). "The cell probe complexity of dynamic data structures". Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing: 345–354.

Theorem 5: Any CPROBE(log n) implementation of the set union problem requires Ω(m α(m, n)) time to execute m Find's and n−1 Union's, beginning with n singleton sets.

- Galil, Z.; Italiano, G. (1991). "Data structures and algorithms for disjoint set union problems". ACM Computing Surveys. 23 (3): 319–344. doi:10.1145/116873.116878.

- Anderson, Richard J.; Woll, Heather (1994). Wait-free Parallel Algorithms for the Union-Find Problem. 23rd ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. pp. 370–380.

- Conchon, Sylvain; Filliâtre, Jean-Christophe (October 2007). "A Persistent Union-Find Data Structure". ACM SIGPLAN Workshop on ML. Freiburg, Germany.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2009). "Chapter 21: Data structures for Disjoint Sets". Introduction to Algorithms (Third ed.). MIT Press. pp. 571–572. ISBN 978-0-262-03384-8.

- Raimund Seidel, Micha Sharir. "Top-down analysis of path compression", SIAM J. Comput. 34(3):515–525, 2005

- Tarjan, Robert Endre (1975). "Efficiency of a Good But Not Linear Set Union Algorithm". Journal of the ACM. 22 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1145/321879.321884.

- Hopcroft, J. E.; Ullman, J. D. (1973). "Set Merging Algorithms". SIAM Journal on Computing. 2 (4): 294–303. doi:10.1137/0202024.

- Robert E. Tarjan and Jan van Leeuwen. Worst-case analysis of set union algorithms. Journal of the ACM, 31(2):245–281, 1984.

- Knight, Kevin (1989). "Unification: A multidisciplinary survey" (PDF). ACM Computing Surveys. 21: 93–124. doi:10.1145/62029.62030.

- Sharir, M.; Agarwal, P. (1995). Davenport-Schinzel sequences and their geometric applications. Cambridge University Press.

External links

- C++ implementation, part of the Boost C++ libraries

- A Java implementation with an application to color image segmentation, Statistical Region Merging (SRM), IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 26(11): 1452–1458 (2004)

- Java applet: A Graphical Union–Find Implementation, by Rory L. P. McGuire

- A Matlab Implementation which is part of the Tracker Component Library

- Python implementation

- Visual explanation and C# code