USCGC Northland (WPG-49)

USCGC Northland (WPG-49) was a United States Coast Guard cruising class of gunboat especially designed for Arctic operations that served in World War II and later served in the Israeli Navy. She was the last cruising cutter built for the Coast Guard equipped with a sailing rig.[4]

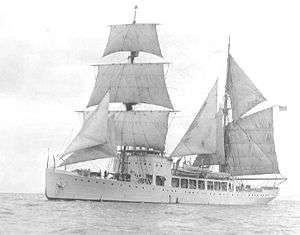

USCGC Northland (WPG-49) circa 1929 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner: | U.S. Coast Guard |

| Builder: | Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Corporation, Newport News, Virginia |

| Cost: | US$865,750[1] |

| Laid down: | 26 August 1926[2] |

| Launched: | 5 February 1927 |

| Commissioned: | 7 May 1927 |

| Recommissioned: | 1939 |

| Decommissioned: | 27 March 1946 |

| Out of service: | 1938–1939 |

| Fate: | Sold 3 January 1947 |

| General characteristics [3] | |

| Displacement: | 2,150 tons, maximum |

| Length: | 216 ft 7 in (66.01 m) |

| Beam: | 38 ft 9 in (11.81 m) |

| Draft: | 16 ft 9 in (5.11 m) max |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | single screw, 4 blades[2] |

| Speed: | 11.7 knots (1927) |

| Range: |

|

| Complement: |

|

| Sensors and processing systems: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: |

|

Design

Northland was designed to be a replacement for the Arctic cutter Bear and was built at Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Corporation, Newport News, Virginia, launched 5 February 1927 and commissioned 7 May.[2] She was 216.6 ft (66.0 m) long, had a maximum displacement of 2,150 tons, and had diesel-electric propulsion driving a single four blade screw. She was originally fitted with auxiliary sails utilizing yards, but they were removed and her tall masts were trimmed in 1936.[3] She was structurally reinforced to withstand hull pressures of 100 psi and lined with cork for warmth. One feature used in the construction was the welding of the hull rather than riveting; this was done for strength and was not a common practice in 1926.[2]

Bering Sea Patrol

After a shakedown cruise, Northland was ordered to San Francisco, California on 7 June 1927. Her homeport was shifted to Seattle, Washington temporarily but she returned to San Francisco in November. On 8 June 1928 Northland arrived in Nome, Alaska to begin her first Bering Sea Patrol. Each May during the years 1929 through 1938 she began a patrol of the Bering Sea where she assisted in the performance of many governmental functions. For the Justice Department she enforced the law, apprehended criminals, and transported floating courts. She gathered military intelligence for the Navy Department, and carried mail for the Post Office Department. For the Interior Department, the cutter carried teachers to their posts, conducted sanitation inspections, and guarded timber and game. Northland surveyed coastlines and regional industries for the Department of Commerce and carried Public Health Service personnel to isolated villages, otherwise without medical service.[3][5]

Northland departed the West Coast in 1938 on her last Arctic cruise, after which she decommissioned. In June 1939, however, she recommissioned and transferred to Boston, Massachusetts to prepare for the second Byrd Antarctic Expedition. With the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Northland was removed from participation in the expedition and was assigned a new homeport at Alameda, California.[3]

World War II service

As a result of the German invasion of Denmark on 9 April 1940, Northland entered the New York Navy Yard to be outfitted for special duty in Greenland in May. She embarked on her first Greenland survey 20 August accompanied by cutters Duane, Modoc, and Raritan with the purpose of charting harbors in order to determine the best location for patrol forces.[3][6] The information that resulted contributed to the composition of a Greenland pilot volume as well as new charts. These were subsequently utilized in the formal organization of the Greenland Patrol, after an agreement between the United States and the Danish government-in-exile was signed 9 April 1941. By that agreement Greenland was included in the United States' system of cooperative defense of the Western Hemisphere.[3]

Northland set out 7 April 1941 on a two-month cruise to assist in the South Greenland Survey Expedition. While conducting this survey she searched for victims of ships sunk in the North Atlantic. While on one of her many mercy missions, she was involved in a near catastrophe. Only six miles from the scene of battle between Bismarck and the British ships that finally sank the giant German warship, Northland was mistaken by the British for a German ship and very nearly taken under fire.

The South Greenland Patrol was organized with the cutters Modoc, Comanche, and Raritan, and the former Coast and Geodetic survey ship Bowdoin. (The Bowdoin being commanded by her original owner and legendary arctic explorer, Commander Donald B. MacMillan.) A month later, the Northeast Greenland Patrol was organized with cutter Northland, former Interior Department ship North Star, and Bear with Captain Edward H. "Iceberg" Smith, USCG, in command.

A month before the consolidation of the two patrols, Northland sighted the German-controlled Norwegian sealer Buskø 12 September and assumed to send a boarding party to investigate. Northland seized Buskø and took it to MacKenzie Bay, on the Greenland coast, where she became the first American naval capture of World War II. It was believed that she had been sending weather reports and information on British shipping to the Germans. A search of Buskø also led to the discovery of a German radio station about five hundred miles up the Greenland coast from Mackenzie Bay. A night raiding party from Northland detained three Germans at Peter Bregt, with equipment and code, as well as German plans for other radio stations in the far north. The cutter was also equipped with an amphibious aircraft, a Grumman J2F Duck, flown by Lieutenant John Pritchard Jr. On multiple occasions, the aircraft was a significant asset in search and rescue as well as military operations. Ultimately, while on a rescue mission involving a downed B-17 bomber aircraft on the Greenland ice cap in November 1942, the "duck" crashed in white-out conditions with Lieutenant Pritchard, Radioman First Class Benjamin A. Bottoms, and a third man rescued from the B-17, killed.[7] Pritchard and Bottoms became the second and third Coast Guardsmen to become missing in action in World War II.

The two Greenland Patrols were consolidated 25 October under Smith and by 1943 the force had grown to include thirty-seven vessels.

Cutter Northland sighted and attacked a submarine in Davis Strait 18 June 1942. The presence of oil and bubbles indicated possible hits from the cutter's depth charges, but German records give no indication of a submarine sinking in this area.

In July 1944 Northland discovered a German trawler believed to be Coburg, which had been fired and completely gutted by her crew. This was one of the ships suspected of carrying three separate German expeditions to Greenland. A second German craft (Kehdingen) was disposed of in September after Northland pursued her for seventy miles (110 km) through ice floes off Great Koldewey Island, The Germans scuttled their ship and then surrendered and were taken on board Northland.

Northland received two battle stars for World War II service. Northland returned to the Treasury Department 1 January 1946 and remained on weather patrol duty until she decommissioned 27 March. Northland had a hand in the desegregation of the United States Coast Guard. While executive officer of the ship, Carlton Skinner, who would later captain the USCGC Sea Cloud, the first integrated warship since the Civil War, witnessed a black steward save the ship. This convinced him that black sailors were just as capable as white sailors.[8]

Service in the Israeli Navy

Although sold for scrap 3 January 1947, Northland was renamed Jewish State, and transported Jewish refugees to Palestine. In 1948 she was renamed Eilat and became the flagship of the infant Israeli Navy. Later, the ship she became a training ship. In 1955, the ship was renamed Matzpen, serving as a barracks or depot hulk. The ship was scrapped in 1961.

Awards

- American Defense Service Medal with "A" device

- American Campaign Medal

- European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with two battle stars

- World War II Victory Medal

See also

- Jonsbu Station

Notes

- Citations

- Johnson, p 113

- Scheina, pp 30–31

- "Northland (WPG-49), 1927"

- Canney, p 97

- Record of Movements, p 246

- Walling, pp 6–8

- Zuckoff, pp 1–8

- Evanson, Coast Guard News

- References used

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- "Northland (WPG-49), 1927" (pdf). Cutters, Craft & U.S. Coast Guard-Manned Army & Navy Vessels. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "Record of Movements, Vessels of the United States Coast Guard, 1790–December 31, 1933 (1989 reprint)" (pdf). U.S. Coast Guard, Department of Transportation. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Canney, Donald L. (1995). U.S. Coast Guard and Revenue Cutters, 1790–1935. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-1-55750-101-1.

- Evanson, Christopher (4 April 2007). "Looking Back: A Veteran Remembers Coast Guard Desegregation". Coast Guard News. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Johnson, Robert Irwin (1987). Guardians of the Sea, History of the United States Coast Guard, 1915 to the Present. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-0-87021-720-3.

- Scheina, Robert L. (1982). U.S. Coast Guard Cutters & Craft of World War II. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-0-87021-717-3.

- Walling, Michael G. (2004). Bloodstained Sea: the U.S. Coast Guard in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1941–1944. International Marine/McGraw-Hill, Camden, Maine. ISBN 978-0-07-142401-1.

- Zuckoff, Mitchell (2013). Frozen in Time. New York, New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-213343-4.