Typhoon Skip

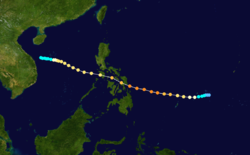

Typhoon Skip, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Yoning, was the final of three tropical cyclones in 1988 to directly impact the Philippines in a two-week time frame. Several areas of disturbed weather developed within the monsoon trough around November 1. One area situated to the south of Guam gradually became better organized, and by late November 3, the system was upgraded into a tropical depression, and a tropical storm later that day. Steady deepening ensued as Skip veered west and the cyclone was upgraded into a typhoon on November 5. The next day, Skip attained its maximum intensity of 145 km/h (90 mph). Shortly after its peak, weakening ensued as the storm tracked across the Philippines. This trend continued once the cyclone entered the South China Sea, initially as a severe tropical storm late on November 7. Slowing down in forward motion, Skip briefly turned west-northwest, then west and finally turned west-southwest before dissipating on November 12.

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

Typhoon Skip on November 6 | |

| Formed | November 3, 1988 |

| Dissipated | November 12, 1988 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 145 km/h (90 mph) 1-minute sustained: 230 km/h (145 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 950 hPa (mbar); 28.05 inHg |

| Fatalities | 237 |

| Damage | $131.8 million (1988 USD) |

| Areas affected | Philippines |

| Part of the 1988 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Skip brought widespread impact to much of the already battered country. On Cebu island, almost 20,000 people were trapped in floodwaters. Along the slope of the Mayon Volcano, 2,600 people had to be evacuated due to a landslide. On the remote island of Palawan, 74 people were killed. Elsewhere, most towns in the Capiz province on Panay Island were flooded. Two people were killed and more than 700 people were evacuated from the Aklan province. In the Iloilo province, on the eastern portion of Panay Island, almost 40 villages were under water and nearby roads were impassable. Seventeen homes were demolished, and two people were confirmed to have been killed because of a landslide in Pasacao in the province of Camarines Sur. Throughout the city, ten people perished. Throughout the province, up to 27 people died and at least 20 others were hurt. In the suburbs of Manila, thirteen people drowned, all in three suburbs, but city proper itself avoided the worst impact from Skip. Overall, 237 people were killed as a result of the typhoon while 35 other people were injured. Throughout the country, damaged totaled $131.8 million (1988 USD).

Meteorological history

The first of two tropical cyclones to form in the basin during November 1988, Typhoon Skip originated from the winter-time monsoon trough dominated by easterly trade winds, a common signal of a La Nina event. Several areas of low pressure developed along the axis of the monsoonal trough. On November 1, an area of disturbed weather was noted near the Philippines; however, this would spawn Tropical Storm Tess instead. The next day, a second area of convection was noticed on weather satellite around 670 km (415 mi) southwest of Guam.[1] At 00:00 UTC on November 3, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) started tracking the system.[2][nb 1] Several hours later, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) followed suit. Satellite pictures at the time showed a well-defined center of circulation at the lower levels of the atmosphere and distinct curved banding features. Based on satellite intensity estimates of 55 km/h (35 mph), the JTWC issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert (TCFA) at 07:00 UTC. Four hours later, the TCFA was re-issued. That evening, following an increase in satellite intensity estimates,[1] both the JMA and JTWC upgraded the system into a tropical storm,[4][nb 2] the latter of which named it Skip.[1]

Skip, while taking the course of a typical "straight runner",[1] the storm made its closest approach to Yap, passing around 100 km (60 mi) to the south.[6] Tropical Storm Skip steadily intensified over a period of several days. Early November 4, the JMA upgraded Skip into a severe tropical storm. Six hours later, the JTWC estimated that Skip attained typhoon intensity,[4] and the following morning, the JMA followed suit.[2] At noon on November 5, the JTWC reported that Skip attained winds of 185 km/h (115 mph), equivalent to a low-end Category 3 hurricane on the United States Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS).[4] The same day, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) also started to follow the storm and assigned it with the local name Yoning.[7] Continuing westward,[1] the JTWC suggested that the typhoon attained winds equal to a Category 4 hurricane on the SSHWS at 00:00 UTC on November 6.[4] At 06:00 UTC, the JTWC increased the intensity of Skip to 230 km/h (145 mph), just shy of super typhoon intensity.[1] Six hours later, the JMA reported that Skip reached its peak intensity, with winds of 145 km/h (90 mph) and a barometric pressure of 950 mbar (28 inHg).[2] Early on November 7, Skip made landfall over Samar in the eastern Philippines.[6]

During the evening of November 7, Skip emerged into the South China Sea[1] as a typhoon and severe tropical storm, according to both the JTWC and JMA respectively.[4] Following a decrease in forward speed, Skip moved west-northwest to the south of a subtropical ridge for the next four days.[1] By early November 10, the JTWC assessed the intensity at 155 km/h (95 mph) while the JMA reported winds of 95 km/h (60 mph). Rapid weakening then began; however,[4] and the JTWC downgraded Skip to a tropical storm later that day.[1] After Skip turned towards the southwest,[6] the JTWC stopped tracking the system early on November 11.[1] After turning west on November 11, and then finally moved to the northwest, Skip dissipated while the center was still offshore, about 220 km (140 mi) east-southeast of Danang on November 12.[2] The remnants of Typhoon Skip continued the linger over the Gulf of Tonkin before fully dissipating.[1]

Preparations

On November 6, storm warnings were posted in Samar, Leyte, and much of the Visayas chain, as well as, for the Bicol Peninsula on Luzon, which was just reeling from the effects of Typhoon Ruby and Tropical Storm Tess, in preparation for the typhoon.[8] The next day, this alert was expanded into the northeastern provinces of Mindanao Island.[9] Simultaneously, a lower level alert was issued for half of Luzon, including the capital of Manila.[10] Small crafts were ordered to stay at port.[11] Philippine Airlines canceled 75 domestic flights as the storm approached.[12][13] The Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) suspended all passenger ship service to ports in the Visayas Islands on November 6, stranding thousands of passengers in Manila and other major ports throughout the nation.[12] Select Military Airlift Command flights to Japan and the United States left early to avoid the core of the typhoon.[14] The city of Manila ordered all schools to close for a day.[15]

Impact and aftermath

Across the Leyte island, the storm knocked nearly 200,000 people without power[12] and caused $400,000 (1988 USD) in damages.[16] On Cebu island, in San Jose, 80% of the city was under water at the height of the storm.[15] One person was killed in Cebu City.[17] Island-wide, almost 20,000 people were trapped in floodwaters.[14] Along the slope of the Mayon Volcano, landslides triggered by heavy rains forced 2,600 people to be evacuated from the slopes of the volcano.[12] All roads were impassible and thirty-nine people were killed in Tablas Island.[18] Elsewhere, three people drowned on Marinduque island.[19] Two fatalities occurred in Tacloban.[17] Two others were killed in Agusan.[20] Skip triggered widespread flooding on the island of Palawan, especially on the southern part of the remote island. There, seventy four people were killed[19][21] and ninety-five were initially listed missing.[17] In a small hamlet of Gilligan on the island of Palawan, the Philippine Red Cross reported that 900 people lost their lives; however, authorities insisted only eight people were killed[21] and that Tropical Storm Tess brought far worse impacts to the region.[22] Nearby, eight casualties occurred in Mindoro.[21] At least 10 small fishing boats went missing off Negros.[17] Moreover, 14 of the 16 towns in Capiz province–located on Panay Island to the southeast of Manila–were flooded,[12] resulting in hundreds of families being evacuated to schools and churches.[12] Greater than 700 people were evacuated from low-lying areas of the Aklan province,[14] where two people perished.[15] In the Iloilo province, on the eastern part of Panay Island, close to 40 villages were under water. Roads around the provincial capital, Iloilo City, were impassible and two major bridges were washed away.[17] Two major bridges were swept away by the typhoon. Throughout Panay Island, eight fatalities were reported, seven of which were drownings while another person was electrocuted by a downed power line.[23] Seventeen homes were demolished,[16] 23 people were buried,[12] and ten bodies were recovered[16] on a landslide in Pasacao in the province of Camarines Sur.[14] Throughout the city, ten people, six of whom were children, were killed.[14] Elsewhere in Camarines Sur, two children died in a tornado.[14] Province-wide, 19 to 27 people perished[24] and at minimum 20 were wounded.[25]

Unlike during Ruby, Manila avoided the inner core of Typhoon Skip,[14] though there were reports of waist-high water in some neighborhoods, forcing residents to use wooden planks and tires to navigate the floodwaters.[26] However, the suburb of Pasig, already inundated by Typhoon Ruby a couple weeks prior, faced additional flooding, resulting in the deaths of seven children.[15] Throughout the metro area, thirteen people drowned, all in three suburbs.[27] A freighter, the Sea Runner, sank in port on Bohol Island due to strong winds and heavy waves from Skip. All 17 crewmen escaped. However, the ship's cargo of 11,250 bags of cement was lost.[12] Nineteen crewmen fled in a life raft when the tanker Ethane ran aground off a small island 110 mi (175 km) south of Manila. A passenger ship, the Sampaguita, sunk just offshore Zamboanga City in the extreme southern portion of the country but all passengers and crew were reported safe. Two small ships, however, were rendered missing.[28]

In all, the storm directly affected 3,027,601 people, or 318,968 families. Nationwide, 146 people were injured.[29] Infrastructure damage totaled $106.2 million (1988 USD), while damage to agriculture accumulated to $16.5 million and damage totaled $8.9 million in private properties. Overall, Skip was responsible for $131.8 million in damage.[30][nb 3] Additionally, 144,136 people or 28,824 families were evacuated to shelters as a result of the flooding. In all, 237 people were killed due to Typhoon Skip.[21][31] Since many roads in the devastated area were impassable, officials were forced to ferry relief goods to stranded residents by small boats and military helicopters.[32] The Canadian Red Cross donated CD$5,000, while the city of Ottawa donated CD$150,000.[33]

See also

Notes

- The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

- Wind estimates from the JMA and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10‑minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1‑minute winds.[5]

- All Philippine currencies are converted to United States Dollars using Philippines Measuring worth with an exchange rate of the year 1988.

References

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1989). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1988 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Japan Meteorological Agency (October 10, 1992). RSMC Best Track Data – 1980–1989 (Report). Archived from the original (.TXT) on December 5, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- "Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Knapp, Kenneth R.; Kruk, Michael C.; H. Levinson, David; J. Diamond, Howard; J. Neumann, Charles (2010). 1988 Skip (1988308N09140). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (April 26, 2004). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions:. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Meteorological Results: 1988 (PDF) (Report). Hong Kong Royal Observatory. 1989. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Padua, Michael V. (November 6, 2008). PAGASA Tropical Cyclone Names 1963–1988 (Report). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Reid, Robert H. (November 6, 1988). "Typhoon Skip Gains Strength As It Heads Towards Manila". Associated Press.

- "Typhoon rushes toward central Philippines". United Press International. November 6, 1988.

- Reid, Robert H. (November 6, 1988). "Storm Warning Posted For Manila As Typhoon Skip Nears". Associated Press.

- "Another Typhoon Headed Toward Philippines". Associated Press. November 6, 1988.

- Arquiza, Yasmin (November 7, 1988). "Typhoon Hits Philippines With Winds Topping 100 Mph". Associated Press.

- Abbuago, Martin (November 7, 1988). "Typhoon Skip lands on Philippines". United Press International.

- Reid, Robert H. (November 7, 1988). "Typhoon Skip Hits Philippines; Thousands Flee Homes". Associated Press.

- Reid, Robert H. (November 8, 1988). "Storm Sweeps Out To Sea After Killing At Least 22". Associated Press.

- Reid, Robert H. (November 7, 1988). "Typhoon Skip Hits Philippines; Thousands Flee Homes". Associated Press.

- "International News". United Press International. November 8, 1988.

- Suarez, Miguel C. (November 9, 1988). "Death Toll From Typhoon Skip at 129". Associated Press.

- Arquiza, Yasmin (November 8, 1988). "Typhoon Skip Leaves At Least 73 People Dead In Philippines". Associated Press.

- Abbuago, Martin (November 9, 1988). "International News". United Press International.

- "Death toll from Typhoon Skip climbs to 237". United Press International. November 11, 1988.

- "Death Toll From Three Typhoons Hits 670, 600 More Missing". Association Press. November 11, 1988.

- "Typhoon Skip Leaves At Least 24 People Dead In Philippines". Associated Press. November 8, 1988.

- "Death Toll From Typhoon Hits 77". Associated Press. November 9, 1988.

- "typhoon skip leaves 26 dead in philippines". Xinhua General Overseas News Service. November 8, 1988.

- "Typhoon Leaves Manila Awes". Toronto Star. November 8, 1988.

- "Death Toll From Typhoon Hits 90". Associated Press. November 9, 1988.

- Jones, David W. (November 8, 1988). "International News". United Press International.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970-2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 9, 2004. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970-2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on March 15, 2005. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Del Mundo, Fernando (November 10, 1988). "Typhoon Skip leaves 191 dead in Philippines". United Press International.

- Mariano, Ann (November 8, 1988). "International News". United Press International.

- "Funds sought for victims of Philippine typhoons". Toronto Star. November 11, 1988. p. A7.