Turquoise parrot

The turquoise parrot (Neophema pulchella) is a species of parrot in the genus Neophema native to Eastern Australia, from southeastern Queensland, through New South Wales and into North-Eastern Victoria. It was described by George Shaw in 1792. A small lightly built parrot at around 20 cm (8 in) long and 40 g (1 1⁄2 oz) in weight, it exhibits sexual dimorphism. The male is predominantly green with more yellowish underparts and a bright turquoise blue face. Its wings are predominantly blue with red shoulders. The female is generally duller and paler, with a pale green breast and yellow belly, and lacks the red wing patch.

| Turquoise parrot | |

|---|---|

| |

| male | |

| |

| female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Genus: | Neophema |

| Species: | N. pulchella |

| Binomial name | |

| Neophema pulchella (Shaw, 1792) | |

| |

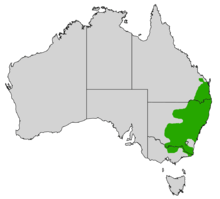

| Turquoise parrot range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Psittacus edwardsii Bechstein, 1811 | |

Found in grasslands and open woodlands dominated by Eucalyptus and Callitris trees, the turquoise parrot feeds mainly on grasses and seeds and occasionally flowers, fruit and scale insects. It nests in hollows of gum trees. Much of its habitat has been altered and potential nesting sites lost. Predominantly sedentary, the turquoise parrot can be locally nomadic. Populations appear to be recovering from a crash in the early 20th century. The turquoise parrot has been kept in captivity since the 19th century, and several colour variants exist.

Taxonomy and naming

Well known around the Sydney district at the time of European settlement in 1788, the turquoise parrot was described by George Shaw as Psittacus pulchellus in 1792.[2] He called it the Turquoisine after its turquoise face patch.[3] The holotype likely ended up in the Leverian collection in England, and was lost when the collection was broken up and sold. German naturalist Johann Matthäus Bechstein gave it the scientific name Psittacus edwardsii in 1811, based on François Levaillant's description of the species as la Perruche Edwards in his 1805 work Histoire Naturelle des Perroquets.[4] Levaillant named it in honour of the English naturalist George Edwards.[5] William Swainson used Shaw's name in 1823 in his work Zoological Illustrations, noting that it was "impossible to represent this superb little creature in its full beauty".[6] Drawing on the previous works, René Primevère Lesson described it as Lathamus azureus in 1830,[4][7] the species name being the Medieval Latin word azureus meaning "blue".[8]

Italian ornithologist Tommaso Salvadori defined the new genus Neophema in 1891, placing the turquoise parrot within it and giving it its current scientific name.[9] There is little geographical variation, with some minor local differences in the amount of orange on the belly.[10] In 1915, Gregory Mathews described a subspecies dombrainii from Victoria on the basis of more prominent red on the scapulars; however, this distinction was not confirmed on review with New South Wales specimens,[4][11] and hence no subspecies are recognised. One of six species of grass parrot in the genus Neophema, it is most closely related to the scarlet-chested parrot.[12] The two are an allopatric species pair,[13] and are the only two species in the genus to exhibit marked sexual dimorphism—where the male and female are different in appearance.[12]

The English common name of the turquoise parrot has varied between chestnut-shouldered parakeet, chestnut-shouldered grass-parakeet, chestnut-shouldered grass-parrot, chestnut-winged grass-parakeet, chestnut-winged grass-parrot,[14] and turquoisine grass parrot, this last name commonly used in aviculture.[15] The name red-shouldered parakeet was incorrectly applied to this species,[16] as it was an alternative name for the paradise parrot.[17]

Description

Ranging from 20 to 22 cm (8–83⁄4 in) long with a 32 cm (12 1⁄2 in) wingspan, the turquoise parrot is a small and slightly built parrot weighing around 40 g (1 1⁄2 oz). Both sexes have predominantly green upperparts and yellow underparts. The male has a bright turquoise-blue face which is darkest on the crown and slightly paler on the lores, cheeks and ear coverts. The neck and upperparts are grass-green, and the tail is grass-green with yellow borders. The wing appears bright blue with a darker leading edge when folded, with a band of red on the shoulder. The underparts are bright yellow, slightly greenish on the breast and neck. Some males have orange patches on the belly, which may extend to the breast. When extended, the wing is dark blue with red on the trailing edge on the upper surface, and black with dark blue leading coverts underneath. The upper mandible of the bill is black and may or may not fade to grey at the base, while the lower mandible is cream with a grey border in the mouth. The cere and orbital eye-ring are grey and the iris is dark brown. The legs and feet are grey.[3]

Generally duller and paler, the female has a more uniform and paler blue face, with highly contrasting cream bare skin around the eye. It lacks the red shoulder band, and the blue shoulder markings are darker and less distinct. The throat and chest are pale green and the belly is yellow. The upper mandible is paler brown-grey with a darker tip, and has been recorded as black while nesting. The lower mandible is pale grey to almost white. When flying, the female has a broad white bar visible on the underwing.[3]

Juvenile birds of both sexes have less extensive blue on their faces, the coloration not extending past the eye. The upperparts resemble those of the adult female.[18] Both sexes have the white wing-stripe, which disappears with maturity in males.[19] The immature male has a red patch on the wing and may also have an orange wash on the belly.[18]

Distribution and habitat

The turquoise parrot is found in the foothills of the Great Dividing Range and surrounding areas.[20] The northern limit of its range is 26° south in southeastern Queensland, around Cooloola, Blackbutt and Chinchilla, extending westwards to the vicinity of St George. Before 1945, it had been recorded as far north as the Suttor River and Mackay. In New South Wales, it is found in a broad band across the central and eastern parts of the state, with its western limits delineated by Moree, Quambone, Hillston, Narrandera and Deniliquin. There have been unconfirmed sightings in the far west of the state. In Victoria it is found in the vicinity of Wangaratta as well as East Gippsland and around Mallacoota.[21] Sightings in South Australia are likely to have been the scarlet-chested parrot,[21] the similar appearance of the females leading to confusion and misidentification.[12]

The turquoise parrot inhabits open woodland and savanna woodland composed either of native cypress (Callitris species) or eucalypts, particularly white box (Eucalyptus albens), yellow box (E. melliodora), Blakely's red gum (E. blakelyi), red box (E. polyanthemos), red stringybark (E. macrorhyncha), bimble box (E. populnea), or mugga ironbark (E. sideroxylon), and less commonly Angophora near Sydney, silvertop ash forest (E. sieberi) in Nadgee Nature Reserve, and stands of river red gum (E. camaldulensis), mountain swamp gum (E. camphora) or western grey box (E. microcarpa) in flatter more open areas. Within this habitat, it prefers rocky ridges or gullies, or transitional areas between different habitats, such as between woodland and grassland or fields in cultivated areas.[20]

The turquoise parrot is considered sedentary and does not migrate, though its movements are not well known. Birds are present in some areas all year, though in northern Victoria they are thought to move into more open areas outside the breeding season. Some populations may be locally nomadic, following availability of water.[22]

Conservation status

Around 90% of the turquoise parrot population resides in New South Wales. The species is not listed as threatened on the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, though a status of near threatened was proposed by Stephen Garnett and Gabriel Crowley in their 2000 work The Action Plan for Australian Birds on account of the significant reduction in distribution.[23] Its population and range have varied wildly; widely distributed across eastern Australia from Mackay to Melbourne up to the 1880s, it vanished from much of its range to the extent that it was presumed extinct in 1915. It was not recorded from Queensland between 1923 and 1950, and Victoria between the mid-1880s and 1949. However, numbers in New South Wales began increasing in the 1930s and the species had repopulated East Gippsland by the 1960s.[22] Tentatively estimated at 20,000 breeding birds in 2000, the population is thought to be still rising.[23]

New South Wales

The turquoise parrot was once common across the Sydney region, and particularly abundant between the localities of Parramatta and Penrith. It dramatically declined in numbers between 1875 and 1895, although rare sightings in western Sydney and the Blue Mountains were recorded in the mid-twentieth century.[2] The turquoise parrot was trapped for the aviary trade and used as pie-filling. Almost all of its preferred habitat, the Cumberland Plain, across western Sydney, had disappeared with development.[24] Over half the woodland in New South Wales, and 80% across Australia has been cleared, and the remaining habitat is fragmented.[25] A key issue is removal of mature eucalypts with resulting loss of hollows available for nesting.[26] The species is thus listed as a Vulnerable species under Schedule 2 of the New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act, 1995 because of habitat destruction (TSC Act).[25] Fire-burning regimes may be resulting in the regeneration favouring shrubs rather than grasses, which are the preferred food source for the species.[23] Feral cats and foxes are a threat, particularly to nesting birds and young.[25]

Victoria

Although formerly common in its range, the species was on the brink of extinction in Victoria by 1917. However, numbers have built up again since the 1930–40s as it reestablished in its former territory.[27] On the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria, this species is listed as near threatened.[28]

Behaviour

-6.jpg)

Turquoise parrots are encountered in pairs or small groups consisting of parents and several offspring, though they may congregate into larger flocks of up to 75 predominantly juvenile birds outside the breeding season. As the breeding season nears, pairs separate out from these flocks.[29] Turquoise parrots roost together communally in autumn and winter.[30] At night they roost among the foliage of trees such as gums or wattles,[21] anywhere from 1 to 8 m (3–25 ft) above the ground.[30] They retreat to trees near their feeding areas during the day.[21] The calls of the turquoise parrot have been little-studied; birds give a high-pitched soft contact call when feeding or in flight, while the alarm call has been described as a high-pitched zitting call. Turquoise parrots also chatter when settling to roost in the evening.[31]

Breeding

The turquoise parrot is monogamous.[29] The male perches upright on a tree stump and extends its wings to show off its red and blue markings when courting a female.[30] Once paired, both sexes look for a nesting site, which is ultimately chosen by the female.[30] Breeding has been reported from Girraween National Park on the New South Wales–Queensland border in the north to Wangaratta and Mallacoota in Victoria.[21] Birds use vertical or nearly vertical hollows of live and dead trees, generally eucalypts, as nesting sites. Occasionally old fence posts have been used. The turquoise parrot competes with—and may be ousted by—the eastern rosella (Platycercus eximius), red-rumped parrot (Psephotus haematonotus) and brown treecreeper (Climacteris picumnus) for suitable breeding sites. The tree containing the hollow is often located in open woodland, and the hollow itself is generally at least 1 m (3 ft) above the ground. Fieldwork in northern Victoria yielded average dimensions of 10 by 6 cm (4 by 3 in) for the hollow entrance, and a depth of around 50 cm (20 in) for the depth of the hole. Elsewhere the average depth is around 76 cm (30 in).[32]

Breeding takes place over the warmer months with eggs laid from August to January. The clutch is laid on a bed of wood dust or leaves and consists of two to five (or rarely up to eight) round or oval glossy white eggs, each of which is generally 21 to 22 mm long by 18 mm (0.8 by 0.7 in) wide. Clutches tend to have more eggs in earlier rather than later clutches, and in nests located further from cleared land. Eggs are laid at an interval of two to three days.[32] Incubation takes 18 to 21 days.[32] The female incubates the eggs and broods the young, and feeds them for their first few days before the male begins helping.[29] She leaves to feed and drink twice a day, once in the morning and once in the afternoon.[32] Both parents take part in feeding the young, on a diet predominantly of seeds with some fruit.[29] The chicks are altricial and nidicolous; that is, they are born helpless and blind and remain in the nest for an extended period. Covered in silvery-white down,[32] they have pink skin and darker blue-grey skin around the eye.[18] By seven days they open their eyes, and are well-covered in grey down with pin feathers emerging from their wings on day six. They are almost covered in feathers by day 21, and fledge (leave the nest) at around 23 days of age in the wild and up to 30 days of age in captivity.[32]

Around 56% of eggs lead to successful fledging of young, with fieldwork in northeastern Victoria yielding an average of 2.77 young leaving the nest. The lace monitor (Varanus varius) and red fox (Vulpes vulpes) are nest predators. Baby birds may perish by overheating in very hot weather, or by being drowned in the hollows after heavy rain.[32]

Feeding

The turquoise parrot is a predominantly ground-based seed eater,[24] foraging in clearings in open woodland, forest margins, and near trees in more open areas such as pastures. It occasionally feeds along road verges and rarely ventures onto lawns.[20] Birds forage in pairs or small troops of up to thirty or even fifty individuals. Observations at Chiltern in Victoria indicated seasonal variation in flock size, with turquoise parrots foraging in groups of 5–30 in winter and 6–8 in spring and summer. Foraging takes place from early in the morning till late afternoon, with a break between midday and mid-afternoon.[22] Birds prefer to feed in shaded areas, where they are better camouflaged in the grass.[30]

Grass and shrub seeds form the bulk of the diet, and leaves, flowers, fruit and scale insects are also eaten.[22] The turquoise parrot has been recorded feeding on seeds of various plant species; more commonly consumed items include the fruit of common fringe-myrtle (Calytrix tetragona), seeds and fruit of erect guinea-flower (Hibbertia riparia), daphne heath (Brachyloma daphnoides), seeds of common raspwort (Gonocarpus tetragynus), Geranium species, black-anther flax-lily (Dianella revoluta) and grass species such as the introduced big quaking grass (Briza maxima) and little quaking grass (B. minor) and members of the genus Danthonia,[29] members of the pea genus Dillwynia, and small-leaved beard-heath (Leucopogon microphyllus). Seed of the introduced common chickweed (Stellaria media) and capeweed (Arctotheca calendula) are also consumed.[27] Nectar of Grevillea alpina,[29] and spores from moss have been recorded as food items.[2]

A female was observed placing leaves of the flaky-barked tea-tree (Leptospermum trinervium) underneath its feathers, leading the observers to wonder whether they were being used to deter or kill insects.[2]

Pathogens

In 1966, a paramyxovirus with some antigenic similarity to Newcastle disease was isolated from the brain of a turquoise parrot in the Netherlands. That year, many aviary species including several species of Australian parrot and members of the genus Neophema had exhibited neurological symptoms reminiscent of Newcastle disease.[33] Like other members of the genus, the turquoise parrot is highly sensitive to avian paramyxovirus infection.[34] It is one of many species of parrot that can host the nematode Ascaridia platyceri.[35]

Aviculture

Initially popular as a caged bird in the 19th century,[36] the turquoise parrot was rarely seen in captivity between 1928 and 1956, the main problem being the high rate of infertile eggs. It has become more common since, and has adapted readily to aviculture. A quiet species, it likes to bathe in captivity.[15] There is a possibility of interbreeding with other members of the genus Neophema if caged together.[37] Specimens with more prominent orange bellies have been bred, sourced from wild birds in New South Wales and not from breeding with scarlet-chested parrots.[37] A yellow form, where the blue pigment is lost and yellow and red pigments are conserved, first appeared in the 1950s in aviculture. It is a recessive mutation.[38] Other colour forms seen are a red-fronted and pied form (both recessive), and jade and olive (dominant).[39]

See also

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Neophema pulchella". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chaffer, Norman; Miller, G. (1946). "The Turquoise Parrot Near Sydney". Emu. 46 (3): 161–67. doi:10.1071/mu946161.

- Higgins 1999, p. 573.

- Australian Biological Resources Study (1 March 2012). "Species Neophema (Neophema) pulchella (Shaw, 1792)". Australian Faunal Directory. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Government. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Levaillant, François (1805). Histoire Naturelle des Perroquets (in French). 1. Paris, France: Levrault, Schoell & Ce. p. 130.

- Swainson, William John (1823). Zoological illustrations, or, Original figures and descriptions of new, rare, or interesting animals : selected chiefly from the classes of ornithology, entomology, and conchology, and arranged on the principles of Cuvier and other modern zoologists. 2. London, United Kingdom: Baldwin, Cradock & Joy. pp. pl. 67.

- Lesson, René Primevère (1830). Traité d'Ornithologie, ou Tableau Méthodique des ordres, sous-ordres, familles, tribus, genres, sous-genres et races d'oiseaux (in French). 1. Paris, France: F.G. Levrault. p. 205.

- Gray, Jeannie; Fraser, Ian (2013). Australian Bird Names: A Complete Guide. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-643-10471-6.

- Salvadori, Tommaso (1891). Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum. Catalogue of the Psittaci, or Parrots. London, United Kingdom: British Museum. pp. 570, 575.

- Higgins 1999, p. 583.

- Cain, A.J. (1955). "A Revision of Trichoglossus haematodus and of the Australian Platycercine Parrots". Ibis. 97 (3): 432–79. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1955.tb04978.x.

- Lendon 1973, p. 253.

- Forshaw, Joseph M. (2010). Parrots of the World. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 134. ISBN 1-4008-3620-4.

- MacDonald, James David (1987). The Illustrated Dictionary of Australian Birds by Common Name. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: Reed Books. ISBN 0-7301-0184-3.

- Shephard 1989, p. 69.

- Lendon 1973, p. 282.

- Lendon 1973, p. 234.

- Higgins 1999, p. 582.

- Lendon, Alan (1940). "The "Wing-stripe" as an Indication of Sex and Maturity in the Australian Broad-tailed Parrots". South Australian Ornithologist. 15: 87–94 [93]. ISSN 0038-2973.

- Higgins 1999, p. 574.

- Higgins 1999, p. 575.

- Higgins 1999, p. 576.

- Garnett, Stephen T.; Crowley, Gabriel M. "The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2000". Threatened species & ecological communities. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 2013-12-27. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Turquoise Parrot". Birds in Backyards. Birdlife Australia. 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- NSW Scientific Committee (June 2009). "Turquoise Parrot Neophema pulchella: Review of Current Information in NSW" (PDF). New South Wales Government. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Landcare NSW (2013). "Turquoise Parrot" (PDF). Communities in Landscapes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Tzaros, Chris (2005). Wildlife of the Box-Ironbark Country. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-643-09983-8.

- Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (2007). Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria – 2007. East Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Sustainability and Environment. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-74208-039-0.

- Higgins 1999, p. 577.

- Higgins 1999, p. 578.

- Higgins 1999, p. 579.

- Higgins 1999, p. 580.

- Smit, Th.; Rondhuis, P.R. (1976). "Studies on a Virus Isolated from the Brain of a Parakeet (Neophema sp)". Avian Pathology. 5 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1080/03079457608418166. PMID 18777326.

- Jung, Arne; Grund, Christian; Müller, Inge; Rautenschlein, Silke (2009). "Avian Paramyxovirus Serotype 3 Infection in Neopsephotus, Cyanoramphus, and Neophema species". Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery. 23 (3): 205–08. doi:10.1647/2008-022.1. JSTOR 27753673.

- Mawson, Patricia M. (1985). "Nematodes (Ascaridia Species) from Some Captive and Feral Parrots". South Australian Ornithologist. 29: 190–91. ISSN 0038-2973.

- Lendon 1973, p. 285.

- Shephard 1989, p. 70.

- Sindel, Stan (1986). "Mutations of Australian Parrots". Panania, New South Wales: The Avicultural Society of New South Wales. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Anderson, Troy (1996). "Neophemas – Care and Management". Parrot Society of Australia. Archived from the original on 2015-04-17. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

Cited texts

- Higgins, P.J. (1999). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 4: Parrots to Dollarbird. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553071-3.

- Lendon, Alan H. (1973). Australian Parrots in Field and Aviary. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-12424-8.

- Shephard, Mark (1989). Aviculture in Australia: Keeping and Breeding Aviary Birds. Prahran, Victoria: Black Cockatoo Press. ISBN 0-9588106-0-5.

External links