Tucuruí transmission line

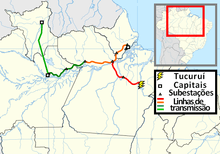

The Tucuruí transmission line (Portuguese: Linhão de Tucuruí) is a hydroelectric power line that leads north from the Tucuruí Dam in Pará, Brazil and crosses the Amazon River. From there the eastern branch leads to Macapá in Amapá and the western branch leads to Manaus in Amazonas. The towers supporting the span across the Amazon River are nearly as high as the Eiffel Tower. Work to extend the line from Manaus north to Boa Vista, Roraima, is due to complete in 2018. There were delays in issuing the environmental permits and then legal challenges since the line crosses the territory of indigenous people who had not been consulted. Although efforts have been made to avoid environmental damage, there has been controversy about the impact of construction and of the tower maintenance corridor.

| Tucuruí transmission line | |

|---|---|

| |

Map of Tucuruí transmission line | |

| Location | |

| Country | Brazil |

| State | Pará, Amapá, Amazonas, Roraima |

| Coordinates | Amazon crossing 1.586588°S 52.760676°W |

| From | Tucuruí, Pará 3.824091°S 49.656290°W |

| Passes through | Vitória do Xingu, Jurupari, Laranjal do Jari, Macapá, Oriximiná, Itacoatiara, Manaus |

| To | Boa Vista, Roraima |

| Ownership information | |

| Operator | LXTE, LMTE, MTE |

| Construction information | |

| Construction started | 2010 |

| Commissioned | 2013 |

| Technical information | |

| Total length | 1,800 km (1,100 mi) |

| No. of transmission towers | 3,600 |

| Power rating | 2,400 MW |

| AC voltage | 500kV / 230kV |

Background

Until recently the areas of Brazil north of the Amazon, including all of the states of Amapá and Roraima, and parts of the states of Pará and Amazonas, were not connected to the Brazilian national electrical power grid.[1] These areas mainly depended on subsidised thermal power generation.[2] The Balbina Dam fails to provide more than 20% of Manaus's electricity.[3] The Linhão de Tucuruí, or the Tucuruí-Macapá-Manaus Interconnection, was built to link the northern communities to the grid to meet growth in power demand, particularly in the Manaus region.[4] Hydroelectric power from the grid could replace most of the expensive and polluting power generation from oil and gas.[5] The project would provide cheaper, cleaner and more reliable electricity and would eliminate the costly thermal generation subsidy.[2]

Technical

The project involved construction of seven double-circuit power lines with a total length of about 1,800 kilometres (1,100 mi) connecting eight substations.[2] Seven of the substations were built from scratch.[5] The grid uses 3,600 transmission towers, with an average span of 500 metres (1,600 ft) between towers. The Amazon River span is 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi).[6]

The project built a double circuit with a voltage of 500 kV between the Tucuruí hydroelectric plant, the second largest in the country, and the Manaus region. It runs through intermediate substations in the municipalities of Anapu, Almeirim, Oriximiná and Silves. A line connecting Amapá to the national grid, a double circuit of 230 kV, runs from the Jurupari substation in Almeirim to substations in Laranjal do Jari and Macapá.[7] The Tucuruí Hydroelectric Dam has an installed capacity of 8,370 MW.[8] The total transport capacity of the high tension lines is 2,400 MW.[8]

Optical fiber cable was run along the transmission lines for use in broadband internet and telephony.[9] The optical network with multiple 100 gigabit per second carriers was installed by TIM Brasil, designed with 17 optical spans. The spans were as long as possible due to the cost and difficulty of maintenance of regeneration sites.[6]

Construction

The project was divided into three construction, operation and maintenance segments.[7] The Spanish company Isolux Corsán won the concessions for lots A and B, and a consortium of Eletronorte, Abengoa and Chesf won lot C.[10] A company was formed for each concession.[7] The lot A section from Tucuruí to Jurupari operated by LXTE is 527 kilometres (327 mi) long. The lot B section operated by LMTE from Oriximiná via Jurupari to Macapá is 713 kilometres (443 mi) long. The lot C section from Oriximiná to Manaus operated by MTE (Manaus Transmissora de Energia) is 586 kilometres (364 mi) long.[7] The estimated cost was about R$3 billion.[5] The project was financed by the Banco de la Amazonía.[9]

Due to the environmental importance of the Amazon region the project had to minimise impact.[11] For this reason the transmission lines mainly run beside existing highways.[8] In many sections unusually high towers had to be built to carry the lines above treetops to avoid cuts.[11] The Isolux Corsán part of the project involved 4,000 workers living in fourteen camps. It included a 70-kilometre (43 mi) section of swamp.[12] In the Alagados region between the Xingu and Amazon rivers the land is flooded in the rainy season and has deep mud in the "dry" season.[13] Use of large barges proved impossible without causing unacceptable environmental damage.[14] The solution was to use specially-built light barges propelled by a hydraulic excavator. The excavator, placed at the front of the barge, would pull it forward using its scoop.[15] Buffalo trails showed where the deepest channels were.[16]

The crossings of the Amazon, Trombetas and Uatumã rivers required huge towers.[17] The line crosses the Amazon at Jurupari island with a 1.2-kilometre (0.75 mi) span between 150 metres (490 ft) towers and a 2.2-kilometre (1.4 mi) span between 295 metres (968 ft) towers.[18] By comparison, the Eiffel Tower in Paris is 324 metres (1,063 ft) high.[9] Zhejiang Electric Power Transmission & Transformation Corporation of China, with the China Cable Corporation and Zhejiang Shengda Steel tower company, built the two largest towers and the main span across the Amazon River. The main span is 2,148 metres (7,047 ft), and the strain section is 3,908 metres (12,822 ft). Four 779.4-millimetre (30.69 in) stranded aluminium lines with a steel core were used for the conductors.[19] The pylons weigh 2,500 tonnes each.[12]

Completion was planned for the end of 2011.[5] In April 2011 it was reported that the first tower had been completed, a 62-metre (203 ft), 24 ton structure on the Oriximiná – Manaus section. The work was now scheduled for completion in December 2012, or at latest in July 2013.[20] The line reached Manaus in 2013.[3] Total investment was US$2.29 billion. According to the government the project would reduce power generation costs by R$2 billion annually.[10][lower-alpha 1] The next phase was a 750-kilometre (470 mi) extension from Manaus to Boa Vista, Roraima.[3]

Roraima extension

The concession to build and operate the line from Manaus north to Boa Vista, Roraima, was auctioned in September 2011 and the agreement with the Transnorte consortium was signed in January 2012. Completion was scheduled for January 2015 at an estimated cost of about R$890 million. Alupar has 51% equity in the consortium and Eletronorte, a subsidiary of Eletrobras, has 49%.[21] The project was stalled due to delays in the licensing process. In the interim, the state remained dependent on the Linhão de Guri from Venezuela, an ageing and unreliable line with steadily less power provided by Venezuela.[22] Boa Vista, a city of over 320,000 people, suffers from constant power outages and blackouts.[21]

The route chosen by Transnorte Energia, the concessionary company, would follow the BR-174 federal highway and was identified as alternative 1 in the 2014 Environmental Impact Assessment, which included studies of the indigenous component.[23] Of the four routes considered, the 721-kilometre (448 mi) alternative 1 had the least environmental impact.[21] 123 kilometres (76 mi) of the line would cross the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory.[24] 250 support towers would be built in the indigenous territory.[25] The only route that completely avoided the territory, 902 kilometres (560 mi) long, would involve opening roads in a better preserved region of the Amazon rainforest, and would cause great pressure to occupy that region. By following the BR-174 infrastructure corridor the chosen alternative would avoid further fragmentation of the forest.[21]

The Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI – National Indian Foundation) issued a letter of consent in November 2015.[24] President Dilma Rousseff announced that a provisional licence would be granted early in December 2015.[22] The preliminary licence was granted to Transnorte Energia by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) on 9 December 2015.[21] In January 2016 the Roraima Secretary for Planning said the connection to the Linhão de Tucuruí should reach Boa Vista in 2018. However, the state was still considering installing another thermoelectric power station to meet immediate demand and was looking into a hydroelectric installation in Caracaraí.[22]

In February 2016 a federal judge issued an injunction that prohibited work on the 500 kV line until the Waimiri-Atroari indigenous people had been consulted. He said IBAMA had ignored the requests of the indigenous people and forced through the project without consultation, as required by the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989. Although public hearings had been held in the cities of Presidente Figueiredo, Manaus, Rorainópolis and Boa Vista, none had been held in the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory.[24] A leader of the indigenous people said FUNAI could not speak on their behalf concerning the project. The Convention required free and informed prior consultation. The Waimiri Atroari had already suffered from a history of "violent pacification", illegal mining and flooding of sacred territories, as with the Balbina Dam.[25] Construction would involve hundreds of workers entering the territory, where FUNAI considers that more than 1,600 Indians are "recent contact". The Indian leaders said that there were already problems in the community and conflicts since BR-174 was opened.[23][lower-alpha 2]

In March 2016 a federal judge responded to a request by the attorney general and suspended the injunction that was preventing construction of the line. He said there had been undue judicial interference in the licensing process for the project, which was of a national strategic nature and would be undertaken entirely on federal land along the BR-174.[26]

Environmental impacts

An environmental assessment document was issued in 2005 that discussed ways to minimise impacts. It covered topics such as the impact on protected areas, land degradation, water pollution, damage to flora and fauna, archaeological and historical sites and community involvement.[27] Given the sensitivity of the Amazon rainforest the environmental impact of the project was the subject of considerable scrutiny. For example, the effect of reduced plant mass in the transmission corridor had to be offset against the savings in greenhouse gas emitted when generating power. However, the estimated net effect is to avoid emissions of 1,460,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent annually.[18]

In March 2013 it was reported that the government was launching an inquiry into the environmental impact of the project in the Manaus region. A public prosecutor asserted that trees had been removed in the Mindu Park in Manaus, violating the environment license.[28] On 7 April 2015 a sum of R$450,000 was allocated to the Uatumã Sustainable Development Reserve to offset the irreversible negative environmental impacts from implementation and operation of the Linhão de Tucuruí.[29] The section to Boa Vista would run through the Adolfo Ducke Forest Reserve, an important research site. A path up to 70 metres (230 ft) wide would be cleared below the power lines to allow for tower maintenance. Many wildlife species would have difficulty crossing such a gap. In 2014 scientists from the National Institute for Amazonian Research expressed concern that the reserve would be isolated and would lose many species.[3]

Notes

- Between 2010 and 2013 the Brazilian Real fluctuated in value from a peak of US$0.64 to a low of US$0.42.

- When BR-174 was opened by the military dictatorship in the 1970s more than 1,100 Indians died through disease or conflict.[21] In 1996 the Indians were given R$1.7 million in compensation for the environmental damage caused by paving BR-174. The Indians continue to block the highway from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. each day to reduce the risk of wild animals and Indians, who hunt by night, being hit by traffic. They are being sued over the blockade by the Roraima government.[21]

Citations

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, pp. 58–59.

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, p. 59.

- Barnett 2014.

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, pp. 58–60.

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, p. 58.

- Clesca 2013.

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, p. 60.

- Cristaldo 2013.

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, p. 62.

- Tucuruí-Macapá-Manaus transmission line – BNA.

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, p. 61.

- 1,191 kilometers of electricity transmission – Isolux Corsán.

- Amaral, Groszownik & Beim 2013, p. 2.

- Amaral, Groszownik & Beim 2013, p. 4.

- Amaral, Groszownik & Beim 2013, p. 6.

- Amaral, Groszownik & Beim 2013, p. 7.

- Doyle De Doile & Nascimento 2010, pp. 61–62.

- ABB telecommunications and substation automation systems ...

- State Grid builds 296-meter high transmission tower ...

- Concluída primeira torre ... amazoniabrasil.

- Trajano 2016.

- Costa 2016.

- Justiça suspende licença – Amazônia Real.

- Justiça suspende licença ambiental ... Folha.

- Licença prévia do linhão do Tucuruí é suspensa...

- Valério 2016.

- Vila do Conde Transmisora de Energia et al 2005.

- Place 2013.

- RDS do Uatumã – ISA, Historico Juridico.

Sources

- 1,191 kilometers of electricity transmission in Amazonas, Isolux Corsán, retrieved 2016-07-27

- ABB telecommunications and substation automation systems for Brazilian transmission project, ABB, 4 August 2011, retrieved 2016-07-28

- Amaral, José Carlos do; Groszownik, Marcelo; Beim, Jorge (2013), Pile driving between the Amazonas and Xingu rivers in the Tucurui Transmission Line. (PDF), Deep Fundations Institute, retrieved 2016-07-27

- Barnett, Adrian (13 June 2014), "Brazil's mega power line threatens Amazon's top reserve", New Scientist, retrieved 2016-07-27

- Clesca, Bertrand (2013), "A Fiber Deployment Project the Size of the Amazon", OSP Magazine, archived from the original on 2016-10-11, retrieved 2017-06-03

- "Concluída primeira torre da linha entre Manaus e Macapá", amazoniabrasil.com (in Portuguese), 5 April 2011, archived from the original on 12 June 2015, retrieved 2016-07-27

- Costa, Emily (6 January 2016), "Interligação de Roraima ao Linhão de Tucuruí só deve ficar pronta em 2018", G1 Globo (in Portuguese), retrieved 2016-07-28

- Cristaldo, Juan Carlos (2013), Xingu and Macapá High Tension Lines, Brazil, Harvard: Zofnass Program, retrieved 2016-07-27

- Doyle De Doile, Gabriel Nasser; Nascimento, Rodrigo Limp (2010), "Linhão de tucuruí – 1.800 km de integração regional" (PDF), T&C Amazônia (in Portuguese), VIII (18), retrieved 2016-07-25

- "Justiça suspende licença ambiental para Linhão de Tucuruí", Folha Web (in Portuguese), Editora Boa Vista, 23 February 2016, retrieved 2016-07-28

- Justiça suspende licença prévia do Linhão de Tucuruí até consulta à indígenas (in Portuguese), Amazônia Real, 2 March 2016, retrieved 2016-07-28

- "Licença prévia do linhão do Tucuruí é suspensa pela Justiça no Amazonas", Portal Amazônia (in Portuguese), 24 February 2016

- Place, Michael (4 March 2013), MPF launches inquiry into US$1.5bn Tucuruí transmission line in Brazil's Amazon, BNA: Business News Americas, retrieved 2016-07-27

- RDS do Uatumã (in Portuguese), ISA: Instituto Socioambiental, retrieved 2016-07-25

- State Grid builds 296-meter high transmission tower in Brazil, highest in South America, ChinaGoAbroad, 29 March 2012, retrieved 2016-07-27

- Trajano, Andrezza (7 January 2016), "Waimiri Atroari não autorizam linhão de Tucuruí em suas terras", Amazônia Real (in Portuguese), retrieved 2016-07-28

- Tucuruí-Macapá-Manaus transmission line, BNA: Business News Americas, retrieved 2016-07-27

- Valério, Luiz (12 March 2016), "Desembargador federal libera continuidade das obras do Linhão de Tucuruí", Boa Vista Agora, retrieved 2016-07-28

- Vila do Conde Transmisora de Energia; Consultoria e Participacoes (JGP) (2005), Relatorio de detalhamento de programas ambientais, Sao Paulo: World Bank, retrieved 2016-07-27