Tropical Storm Fay (2020)

Tropical Storm Fay was the first tropical cyclone to make landfall in the U.S state of New Jersey since Irene in 2011. The sixth named storm of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, Fay was the earliest sixth named storm on record in the basin when it formed on July 9. Fay originated from a surface low that formed over the northern Gulf of Mexico on July 3 and slowly drifted east before crossing over the Florida Panhandle and drifting across the southeastern United States as a well-defined surface low, emerging off the coast of North Carolina on July 8. From there, the storm utilized favorable conditions for cyclogenesis and coalesced into a tropical storm on July 9. The storm intensified before shifting west and landfalling in New Jersey later on July 10. After making landfall, the storm lost deep convection and degenerated into a post-tropical cyclone on July 11.

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Tropical Storm Fay at peak intensity shortly before landfall in New Jersey on July 10 | |

| Formed | July 9, 2020 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | July 12, 2020 |

| (Extratropical after July 11) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 60 mph (95 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 998 mbar (hPa); 29.47 inHg |

| Fatalities | 6 total |

| Damage | $400 million (2020 USD) |

| Areas affected | Southeastern United States, East Coast of the United States, Eastern Canada |

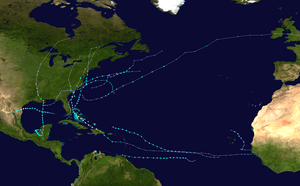

| Part of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Fay brought high winds and stormy weather to much of the Mid-Atlantic and the Northeastern United States, with the heaviest rains west of Long Island. Six people were killed by rip currents and flooding related to the storm. Many intenstates and other principle highways throughout the Philadelphia and New York City Metro were flooded and impassable, leading to widespread road closures and disruption to commuters. Downed trees and wires caused power outages in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Overall, Fay caused an estimated US$400 million in damage to the U.S. East coast, making the storm the costliest tropical cyclone to hit the Northeast since Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Meteorological history

The origins of Fay were from a mesocyclonic vortex over the deep south. The MCV merged with a trough that extended from the Gulf of Mexico to the western Atlantic Ocean.[1] Late on July 4, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) first mentioned the possibility of eventual tropical cyclone formation from the trough in the northern Gulf of Mexico, which at that time consisted of disorganized convection, or thunderstorms.[2] A day later, a low pressure area formed near the northern Gulf Coast, which soon moved ashore the Florida panhandle.[3][4] The low moved into Georgia on July 6, and into South Carolina two days later, accompanied by a large area of thunderstorms over the southeastern United States. By that time, the NHC assessed a 50% probability that the weather system would become a tropical or subtropical cyclone, which the agency soon raised to 70%.[5][6] The low's associated convection moved over the western Atlantic Ocean as a large area of disorganized thunderstorms.[7] On July 9, the thunderstorms increased and organized near the Outer Banks of North Carolina.[8]

Late on July 9, the Hurricane hunters flew into the weather system and detected a circulation center near the edge of its thunderstorms, which indicated a reformation of the original low. Based on the organization of the system, and observations of 45 mph (75 km/h) sustained winds, the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Storm Fay at 21:00 UTC on July 9. The storm was located over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream and in an area of light to moderate wind shear. These environmental factors favored some intensification.[9] The elongated circulation of the developing storm was steered generally northward by a ridge over the western Atlantic Ocean and an approaching trough on the opposite side.[10] Fay strengthened slightly on July 10, despite southwesterly wind shear which exposed the circulation from the main area of thunderstorms,[11] causing it to entrain dry air. That day at 15:00 UTC, the NHC estimated peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). At that time, Fay had a small circulation center just east of the Delmarva peninsula, which was rotating around a larger circulation with subtropical appearance on visible satellite imagery.[12] Around 21:00 UTC on July 10, Fay made landfall just north-northeast of Atlantic City, New Jersey, with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h).[13] By that time, the system was losing some of its tropical characteristics, with decreasing amounts of thunderstorms associated with the center and the deepest convection displaced well to the east and southeast of the center.[14] Fay continued weakening as it moved northward through New Jersey.[15] Fay weakened into a tropical depression as it crossed into southeastern New York,[16] and then transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone as the center became devoid of deep convection early on July 11.[17] Afterward, Fay's remnants were drawn into the circulation of an approaching extratropical storm, before being fully absorbed into the approaching system over Quebec on July 12.[18]

Preparations

Upon issuing its first advisory on Fay, the NHC issued a tropical storm warning from Cape May, New Jersey to Watch Hill, Rhode Island, including Long Island and Block Island.[19] On July 10, the NHC extended the warning southward to Fenwick Island, Delaware, including the Delaware Bay.[20] The National Weather Service issued a flash flood watch for much of the Eastern Shore of Maryland, all of New Jersey, and New York City.[21][22][23] New York's Long Island was under a flash flood warning.[24]

President Donald Trump's rally in Portsmouth, New Hampshire was delayed due to possible impacts from Fay. Due to concerns about the COVID-19 Pandemic, the rally was supposed to be held outdoors. However, forecasters expected heavy rainfall and gusty winds from Fay or its remnants, which led the Trump campaign to postpone the rally due to safety reasons.[25]

Lifeguards restricted swimming in three Delaware beaches due to the threat for rip currents.[26]

Impact

The precursor disturbance to Fay moved into the Florida Panhandle and crossed over into Georgia on July 6, delivering heavy rainfall throughout the state and causing widespread flash flooding as far as the Savannah River valley.[27] Augusta, Georgia recorded its wettest July day on record, a record that stood since 1887.[27] Many roads in South Carolina were deemed inaccessible and became flooded, while one road became completely washed out.[28] Hunting Island State Park in South Carolina recorded at least 12.75 inches (323 mm) of rain due to the disturbance.[29] Beachgoers on the North Carolina coast observed two waterspouts, with one of them coming ashore and becoming an EF0 tornado, which lofted an umbrella.[30][31][32]

While Fay was near peak intensity, its rainbands produced gale force winds along the Delaware coast,[33] with sustained winds of 47 mph (76 km/h) and gusts as high as 57 mph (92 km/h) recorded near Long Neck. The storm downed trees and power lines in Long Neck and Nassau. Rainfall in the state reached 6.97 in (177 mm) near Lewes. Storm rainfall caused flooding in Sussex County, reaching 2.5 ft (0.76 m) deep in Bethany Beach.[34] Floodwaters covered portions of Delaware Route 1, including just south of the Indian River Inlet Bridge. The intersection of Delaware Route 1 and Delaware Route 54 in Fenwick Island was flooded, where a vehicle knocked down a pedestrian signal pole at the intersection. There was minor beach erosion along the Delaware Beaches.[35][36] Tidal flooding also occurred farther north in the state along the Christina River in New Castle County.[34] Fay also caused flash flooding in neighboring Pennsylvania, with a rainfall total of 5.26 in (134 mm) recorded in Wynnewood. At least six drivers required rescue when their vehicles were flooded. The storm also knocked down trees and power lines across eastern Pennsylvania.[34]

In neighboring New Jersey, Fay also dropped heavy rainfall, reaching 5.86 in (149 mm) near Wildwood Crest. The storm caused flooding in several Jersey Shore towns including Wildwood, North Wildwood, Sea Isle City, and Ocean City, with streets covered in water and some road closures.[35] Flooded roads included portions of the New Jersey Turnpike; Interstates 287 and 295; U.S. Routes 9, 30, 202, 322; and several state and local roads. Sustained winds in New Jersey reached 44 mph (71 km/h) near Strathmere, with gusts to 53 mph (85 km/h). The winds knocked down trees and power lines, causing some road closures.[34] An 18-year-old swimmer drowned in Atlantic City. A 77-year-old swimmer and a 17-year-old swimmer were pulled from the ocean at Atlantic City and Raritan Bay respectively on Thursday and later died from their injuries.[37] A 24-year-old man went missing while swimming and was presumed dead by authorities in Ocean City, New Jersey.[38] On July 18, 2020 a fisherman off the Great Egg Harbor Inlet discovered the deceased body of the missing man.[39]

In Long Beach, New York, a 19-year-old drowned after being caught in rip currents related to Fay. He was with five other swimmers, who were rescued after also being caught in the rip currents.[40] The storm flooded several New York City Subway stations.[41] A 64-year-old Massachusetts man was identified as a victim of a drowning off a Rhode Island beach.[42] Overall, losses from the storm on the US Eastern Coast were estimated at a preliminary US$400 million based off wind and storm surge damage on residential, commercial, and industrial properties.[43]

See also

- List of New Jersey hurricanes

- List of New England hurricanes

- Other storms of the same name

- Tropical Storm Danielle (1992) – struck the same area at a similar intensity with similar effects.

- Hurricane Irene - caused catastrophic damage to New Jersey and surrounding areas as a much larger tropical storm.

- Hurricane Sandy – another caused catastrophic damage in the same regions in 2012 as a hurricane-force post-tropical cyclone.

References

- @pppapin (July 4, 2020). "twitter.com/pppapin/status/1279501935377133569" (Tweet). Retrieved 2020-07-10 – via Twitter.

- "Tropical Weather Outlook". NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL. 2020-07-04. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Tropical Weather Outlook". NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL. 2020-07-05. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Tropical Weather Outlook". NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL. 2020-07-05. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Tropical Weather Outlook". NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL. 2020-07-06. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Tropical Weather Outlook". NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL. 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Weather Outlook". NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL. 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Weather Outlook". NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL. 2020-07-09. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Discussion Number 1". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-09. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Discussion Number 2". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-09. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Discussion Number 3". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Discussion Number 5". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Discussion Number 6". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Discussion Number 6". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Forecast Discussion Number 7". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Tropical Depression Fay Intermediate Advisory Number 7A". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-11. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Post-Tropical Cyclone FAY". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "WPC Surface Analysis valid for 07/12/2020 at 12 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. July 12, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Advisory Number 1". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-09. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Tropical Cyclone Update". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Maryland Weather: Tropical Storm Fay Forms; Flash Flood Watch For Parts Of Maryland". 2020-07-09. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- NJ.com, Len Melisurgo | NJ Advance Media for (2020-07-09). "Atlantic storm strengthens into Tropical Storm Fay, N.J. under tropical storm warning". nj. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Brings Several Inches of Rain, Strong Winds, Flooding". www.ny1.com. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay headed for LI; warning in effect, forecasters say". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Trump's New Hampshire Rally delayed because of Tropical Storm Fay". cnn.com. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Neiburg, Maddy Lauria and Jeff. "Tropical Storm Fay brings rain, rough surf to Delaware; some beaches closed to swimming". The News Journal. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Drenches the Mid-Atlantic, Northeast (RECAP)". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Low Pressure Is Likely to Form Into a Tropical or Subtropical Depression or Storm as it Spreads Rain Along East Coast". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Impressive rain at @HuntingIslandSP the last couple of days". Twitter. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Ominous towering vortex leaves puzzled North Carolina beachgoers asking: 'Do we run?'". The News Observer.

- US National Weather Service Newport/Morehead City NC on Facebook Watch, retrieved 2020-07-11

- NWS Damage Survey for 07/06/20 Tornado Event (Report). Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Wilmington, North Carolina. July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm FAY". NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER and CENTRAL PACIFIC HURRICANE CENTER. 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- https://www.weather.gov/phi/EventReview20200710

- Scott, Katherine; McCormick, Annie; Katro, Katie (July 10, 2020). "Tropical Storm Fay causing flooding at New Jersey shore towns". Philadelphia, PA: WPVI-TV. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm Fay Causes Flooding, Damage Along Delaware's Coast". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. July 10, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- "Teen who disappeared in rough surf at Jersey Shore presumed dead, cops say". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Swimmer goes missing trying to rescue family members at the Jersey Shore". July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Brandt, Joe (2020-07-18). "Fisherman Finds Body in Inlet 6 Days After Swimmer Went Missing". NBC10 Philadelphia. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- "Teen drowns, 5 rescued from strong currents in Long Beach". WPIX. 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- Choi, Morgan Chittum, Elize Manoukian, Anna. "SEE IT: Heavy downpour from Tropical Storm Fay floods Times Square subway station as winds pick up speed". nydailynews.com. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- Jackson Cote (July 14, 2020). "64-year-old Matthew Smith of Fitchburg identified as victim of drowning off Scarborough Beach in Rhode Island". Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "East Coast's Insured Loss From Tropical Storm Fay to Tally Near $400 Million: KCC". Insurance Journal. 2020-07-15. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

External links