Tropical Storm Allison (1989)

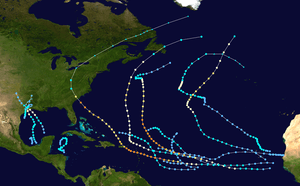

Tropical Storm Allison was a tropical cyclone that produced severe flooding in the southern United States. The second tropical cyclone and the first named storm of the 1989 Atlantic hurricane season, Allison formed on June 24 in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Development of Allison was a result of the interaction of a tropical wave and the remnants of Pacific hurricane Hurricane Cosme. It moved south and became a tropical storm on June 26. By June 27, Allison made landfall near Freeport, Texas. Allison quickly weakened to a tropical depression later that day, and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on the following day.

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

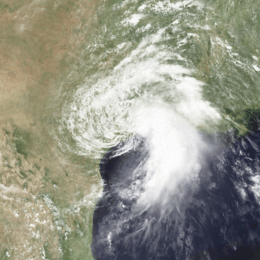

Tropical Storm Allison at peak intensity making landfall in Texas on June 26 | |

| Formed | June 24, 1989 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | June 28, 1989 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 50 mph (85 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 999 mbar (hPa); 29.5 inHg |

| Fatalities | 11 direct |

| Damage | $560 million (1989 USD) |

| Areas affected | East Texas, Louisiana |

| Part of the 1989 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The storm caused heavy rainfall, amounting to 30 in (760 mm) in some places. In total, 11 fatalities resulted from the storm, as well as $560 million (1989 USD, $1.16 billion 2020 USD) in damage.

Meteorological history

Three meteorological phenomena combined to produce Tropical Storm Allison. First, Hurricane Cosme moved northward through Mexico in response to a strong mid to upper-level ridge. Its remnants entered the Gulf of Mexico on June 22, when a westward moving tropical wave reached the area. Finally, a strong anticyclone over the Gulf allowed for the disturbed area to organize into Tropical Depression Two in the western Gulf of Mexico on June 24.[1]

The depression continued to organize as it drifted to the north, and became Tropical Storm Allison on June 26 off the Texas coast.[1] A ridge to Allison's north weakened in response to an approaching frontal trough, and the tropical storm accelerated to the north. Allison reached a peak of 50 mph (80 km/h) winds just before hitting near Freeport, Texas on June 27. It turned to the northeast with the front, weakened to a tropical depression on June 27, and became extratropical on June 28.[2]

The frontal trough outran the system, and the building ridge to Allison's north forced the extratropical depression turned to the south and southwest. After executing a cyclonic loop over Texas, the ridge to the north began to erode, allowing Allison to track northeast and out of the state. Its circulation dissipated on July 1, but the remnants retained some organization, and continued to the northeast. On July 3 and July 4, the shortwave that influenced the remnants of Allison accelerated ahead of the storm, causing Allison to become stationary over the borders of Kentucky, Illinois, and Indiana. A second shortwave trough brought the remnants of Allison southward into Alabama. It turned to the northwest, and the remnants of Allison became unidentifiable over Arkansas on July 7.[2]

Preparations

In preparation for Tropical Storm Allison, a tropical storm watch was issued on June 24 for Baffin Bay, Texas to Morgan City, Louisiana. By June 26, this alert was upgraded to a tropical storm warning. All advisories were discontinued the next day.[3]

Impact

Texas

The slow movement of Allison and its remnants resulted in heavy rainfall over East Texas, with some areas receiving more than 20 inches (510 mm). Severe flooding occurred, with more than 6,200 homes suffering water damage, which forced hundreds of residents to evacuate and stranding thousands of other people. Losses in Texas were estimated between $200 million and $400 million. Additionally, there were three deaths in the state, all of which due to drowning. In Brazoria County, rainfall amounts were generally between 6 and 7 inches (150 and 180 mm), causing flooding in the West Columbia area. Precipitation up to 10 inches (250 mm) in Chambers County inundated many streets and caused water intrusion into several homes. Along the Trinity Bay, tides reached almost 7 feet (2.1 m) above normal at Anahuac. Low-lying areas around the mouth of the Trinity River were completely submerged for several days.[4]

Local flooding was reported in Galveston County due to rainfall amounts of 4 to 8 inches (100 to 200 mm), particularly in Clear Lake, Galveston Island, Kemah, and Texas City. The highest storm surge in the area was 3.9 feet (1.2 m) above mean sea level, causing some beach erosion. An estimated 20 to 30 yards (60 to 90 ft) of sand was washed away, while Texas State Highway 87 was closed due to sand and debris spewed onto the roadway from the storm surge. Wind gusts up to 56 mph (90 km/h) downed some trees limbs and power lines. Additionally, a tornado was spawned in Gilchrist and caused minor damage and one injury. In Hardin County, rains of 6 to 8 inches (150 to 200 mm) fell. The Pine Island Bayou overflowed, flooding homes in Pinewood Estates and Silsbee.[4]

Up to 10 inches (250 mm) of rain fell in the southern portions of Liberty County. As a result, significant flooding occurred along the Trinity River. In Liberty and Moss Bluff, Texas, residents of 8 subdivisions were left isolated. Throughout the county, an estimated 2,500 people became stranded. Major streets in Dayton were inundated by as much as 6 feet (1.8 m) of water. About 3,000 homes were flooded, with 500 people fleeing for higher ground. In Jasper County, precipitation amounts reaching 9 inches (230 mm) caused flooding in Buna and Kirbyville, as well as low-lying areas around the Sabine River. Throughout Matagorda County, several streets and low-lying areas were inundated by water due to rainfall amounts up to 10 inches (250 mm). Similar amounts of precipitation amounts in Montgomery County caused flooding along the San Jacinto River and Caney and Spring Creeks. Low-lying areas were submerged along the Sabine River in Newton County, due to up to 8 inches (200 mm) of rainfall. The Sabine River also exceeded its banks in Orange County, flooding several homes and streets.[4]

In Jefferson County, up to 8 inches (200 mm) of rainfall was reported. Significant flooding occurred in areas around the Hillebrandt Bayou. About 200 homes and 50 businesses in Beaumont received water damage, with losses estimated nearly $1.5 million. Throughout the county, damage reached about $2.8 million. Two teenage boys drowned in Beaumont, after the raft they were riding on capsized and subsequently swept into a drainage pipe. Along the coast, storm surge ranged between 2 and 4 feet (0.61 and 1.22 m) in height along the Bolivar Peninsula. This caused minor beach erosion in Jefferson County, while portions of Texas State Highway 87 was also closed here due to sand and debris washed onto the roadway. Wind gusts in the county peaked at 46 mph (74 km/h).[4]

Elsewhere

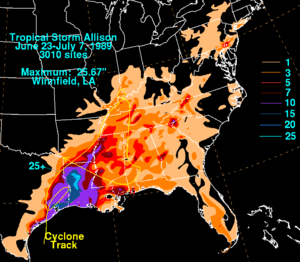

While Allison's winds were not overly strong, it caused tremendous flooding in Texas and Louisiana, with 20 to 25 in (510 to 640 mm) in of rain occurring in some locations. The local hardest hit by the flooding was Winnfield, Louisiana, which experienced almost 30 in (760 mm) of rain from June 26 to July 1.[5][6]

Rainfall from the storm extended eastward into the Mid-Atlantic States, producing flooding.[7] In Delaware, the rainfall led to record breaking discharge rates at three gauging stations, while one-third of the state's gauging stations reported significant discharges.[8]

13.9 in (350 mm) of rain fell at a site in Arkansas, the highest rainfall total from a tropical cyclone in the state.[9]

Eleven people were reported killed from the storm. Three deaths occurred in Texas, five in Mississippi and three in Louisiana. Two teenage boys were killed when their raft got sucked into a drainage pipe from the runoff of Allison in Beaumont, Texas. An eighteen-year-old was killed in Harris County, Texas from drowning during a swim. The eight final deaths in Louisiana and Mississippi were by drowning. The extreme flooding in turn led to heavy damage, amounting to around $560 million (1989 USD).[10]

See also

References

- Case, Robert (16 August 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Case, Robert (16 August 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Case, Robert (16 August 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page 10". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena: June 1989 (PDF). National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Climatic Data Center's Storm Data Reports. Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 85–86. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- Case, Robert (16 August 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page 3". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Roth, David (1 May 2007). "Tropical Storm Allison - June 24-July 7, 1989". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- "Summary of Significant Floods in the United States, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, 1970 Through 1989". United States Geological Survey. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- "Summary of Significant Floods in the United States, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, 1970 Through 1989". United States Geological Survey. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (January 7, 2013). "Maximum Rainfall caused by Tropical Cyclones and their Remnants Per State (1950–2012)". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- Case, Robert (16 August 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page 4". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tropical Storm Allison (1989). |