Trinidad Regional Virus Laboratory

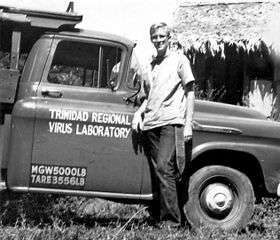

The Trinidad Regional Virus Laboratory (T.R.V.L.) was established in Port of Spain, in 1953 by the Rockefeller Foundation in co-operation with the Government of Trinidad and Tobago. It was originally housed in an old wooden army barracks near the docks in Port of Spain. A large wired-in "animal house" was built out back to house the many wild animals brought in for study.

The Virus lab's first Director was the renowned epidemiologist, Dr Wilbur Downs who served in that role until 1961. In that year the laboratory was moved to new buildings at Federation Park, Port of Spain and, in 1964, became part of the Department of Microbiology of the University of the West Indies under the direction of Dr Leslie Spence, who had been with the laboratory since 1954. It is now part of the Caribbean Epidemiology Center (Carec) in Port of Spain.

Scientific community in Trinidad in the 1950s and 60s

The laboratory was one of four tropical virus research laboratories sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation during the 1950s, including one in Brazil and two in Africa.

Under the inspired leadership of Dr Downs the laboratory began intensive research programs and made many new discoveries including the isolating of several arthropod-borne disease-causing viruses, and new insights into the epidemiology of key virus diseases including yellow fever, dengue fever, and rabies.

Downs headed a team of dedicated researchers including Dr. Charles R. Anderson (Virologist), Dr Leslie Spence (Epidemiologist), Dr Thomas Aitkens (Entomologist) and Dr Brooke Worth (Mammologist and Ornithologist). They worked very closely with other scientists in Trinidad, particularly those at the New York Zoological Society's research station headed by Dr William Beebe, the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture, the Trinidad and Tobago Health and Agriculture Departments, Arthur M. Greenhall, a world expert on vampire bats, and Dr A. E. Hill, a specialist in Tropical and Internal Diseases, with a particular interest in Dengue fever.

The flourishing scientific community centered around the T.R.V.L., the New York Zoological Society's field station at Simla, and the Imperial College of Agriculture, provided an exciting pool of top-notch scholars whose interests often extended well past their immediate jobs. Much useful research was accomplished in these years in fields as diverse as archeology, the mating of butterflies and fiddler crabs, ornithology, and parasitology.

The laboratory also played host to constant stream of distinguishing visiting scientists from around the world, many of them conducting cutting-edge research in their fields, as well as photographers and illustrators from the National Geographic and other magazines, as well as providing first-class training and jobs for local people.

Yellow Fever Epidemic

The discovery of a sick Red Howler monkey, (who was found to be suffering from yellow fever) in 1953 provided the first indication that yellow fever was still endemic in Trinidad although there had not been a case reliably reported from Trinidad since an outbreak in 1914.

It was discovered that a form of the disease "jungle yellow fever" was carried by Red Howler monkeys (Alouatta macconnelli Elliot) who provided a continuous reservoir for the disease and spread by the Haemagogus s. spegazzini mosquito which normally inhabits rainforest regions, both at ground level and in the treetops.

After Government felling of large stands of native forest, yellow fever was isolated from a patient from Cumaca in the northern range in 1954. It soon began to spread to humans and be transmitted by the common Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Blood specimens were taken from over 4,500 humans in late 1953 and early 1954, and checked to detect the presence of a wide variety of known viruses. Over 15% showed antibodies to yellow fever and more human cases quickly followed.

Warnings were made that an epidemic was imminent and Downs and Hill began a program of inoculating health workers and stockpiling vaccine. Trinidad health authorities followed up with large-scale vaccination and intensive anti-aegypti measures including public education, regular inspection for breeding sites, and spraying of domestic residences with DDT. In spite of these measures, and the fact that an estimated 80% of the population of Port of Spain were immune to yellow fever and dengue, several more cases were soon reported. Most probably due to the health measures taken it did not develop into a widespread epidemic in Trinidad itself.

An attempt was made to totally quarantine the island just before Christmas, 1954, but the disease quickly spread to the nearby mainland of Venezuela and, from there, all the way to southern Mexico, probably killing several thousand people in the process.

Virus sampling and identification

Large-scale surveys were made of viruses and antigens in the local population, as well as domestic and wild animals. At the time the laboratory was established there were a number of common but unidentified disease-causing virus fevers in Trinidad, usually referred to by descriptive names such as "Trinidad 3-day fever", Trinidad 5-day fever", and the like. Some of these were soon isolated and identified.

A semi-permanent bush camp was set up at Bush Bush Wildlife Sanctuary in the large Nariva Swamp in southeastern Trinidad and a large tree station was built in the Vega de Oropouche rainforest near Sangre Grande with platforms at 60, 90 and 120 feet (18, 27 and 36.6 metres) to facilitate collecting mosquitoes at various levels in the rainforest, including the forest canopy.

Rabies and bats

Dr. H. Metivier, a Veterinary Surgeon, who established in 1931 the connection between the bites of bats and paralytic rabies, and Dr. J. L. Pawan, a Government Bacteriologist found Negri bodies in the brain of a bat with unusual habits in September 1931, finally demonstrated that rabies could be transmitted to humans by the infected saliva of vampire bats. In 1934, the Government began a program of vampire bat control, shooting, netting and trapping, while encouraging the screening off of livestock buildings and free vaccination programs for exposed livestock.

After the opening of the Virus laboratory in 1953 basic research on bats and the transmission of rabies progressed rapidly under the able direction of Arthur Greenhall, a Government Zoologist.

Some of the main viruses isolated at T.R.V.L. (new discoveries marked with an asterisk):

- Yellow fever

- Dengue fever

- Ilhéus virus

- Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus

- St. Louis virus

- Mayaro virus*

- Oropouche virus*

- Tacaribe virus* (isolated in 1956 from a bat)

References

- Virus Diseases in the West Indies - a special edition of the Caribbean Medical Journal. Vol. XXVI, Nos. 1-4, 1965.

- Beard, J. S. (1946) The natural vegetation of Trinidad. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Brown, N.A. 2000. Environmental advocacy in the Caribbean: The case of the Nariva Swamp, Trinidad. CANARI Technical Report No. 268. PDF

- Sletto, B. 2002. Producing space(s), representing landscapes: maps and resource conflicts in Trinidad. Cultural Geographies 9: 389-420 abstract

- Theiler, Max and Downs, W. G. The Arthropod-Borne Viruses of Vertebrates: An Account of the Rockefeller Foundation Virus Program, 1951-1970. Yale University Press, 1973.

- Waterman, James A. 1965. "The History of the Outbreak of Paralytic Rabies in Trinidad Transmitted by Bats to Human Beings and the Lower Animals from 1925." The Caribbean Medical Journal. 1954. Vol. XXVI, Nos. 1-4, pp. 164–169.

- Fleming, Theodore H. 2003. A Bat Man in the Tropics: Chasing El Duende. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23606-8.

- Greenhall, Arthur M. 1961. Bats in Agriculture. Ministry of Agriculture, Trinidad and Tobago.

- Goodwin G. G., and A. M. Greenhall. 1961. "A review of the bats of Trinidad and Tobago." Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 122: 187-302.

External links

- "Bush Bush Forest and the Nariva Swamp" by Thomas H. G. Aitken

- Official website of the Caribbean Epidemiology Center

- Short history of the Caribbean Epidemiology Center and T.R.V.L. with a couple of photos

- World Health Report on Yellow Fever

- World Health Organization factsheet on Rabies

- World Health Organization factsheet on Rabies vaccine