Tricca

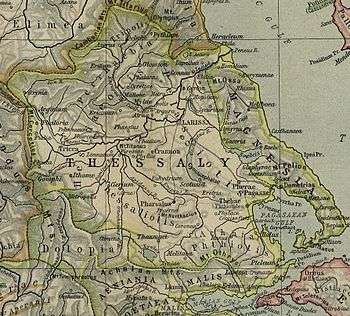

Tricca or Trikka (Ancient Greek: Τρίκκη or Τρίκκα) was a city and polis (city-state)[1] of ancient Thessaly in the district Histiaeotis, standing upon the left bank of the Peneius, and near a small stream named Lethaeus.[2] This city is said to have derived its name from Tricca, a daughter of Peneius.[3] The modern city of Trikala extends over the ancient site.[4]

It is mentioned in Homer as the kingdom of Machaon and Podaleirius, sons of Asclepius and physicians of the Greek army, who led the Triccaeans to the Trojan War.[5] It possessed a temple of Asclepius, which was regarded as the most ancient and illustrious of all the temples of this god.[6] This temple was visited by the sick, whose cures were recorded there, as in the temples of Asclepius at Epidaurus and Cos.[7] There were probably physicians attached to the temple; and 19th century archaeologist William Martin Leake reports an inscription in four elegiac verses, to the memory of a "god-like physician named Cimber, by his wife Andromache," which he found upon a marble in a bridge over the ancient Lethaeus.[8]

In the edict published by Polysperchon and the other generals of Alexander the Great, after the death of the latter, allowing the exiles from the different Greek cities to return to their homes, those of Tricca and of the neighbouring town of Pharcadon were excepted for some reason, which is not recorded.[9] Tricca was the first town in Thessaly at which Philip V of Macedon arrived after his defeat at the Battle of the Aous (198 BC).[10] Tricca is also mentioned by Liv. 36.13; Plin. Nat. 4.8. s. 15 Ptol. 3.13.44; Them. Orat. xxvii. p. 333.

Procopius, who calls the town Tricattûs (Τρικάττους), says that it was restored by Justinian;[11] but it is still called Tricca by Hierocles[12] in the sixth century, and the form in Justinian may be a corruption. In the twelfth century it already bears its modern name Trikkala (Τρίκκαλα)

The castle occupies a hill projecting from the last falls of the mountain of Khassia; but the only traces of the ancient city which Leake could discover were some small remains of Hellenic masonry, forming part of the wall of the castle, and some squared blocks of stone of the same ages dispersed in different parts of the town.[13] The remains are in a section of modern Trikala called Agios Nikolaos.[14]

Tricca was Christianised early and is attested as an episcopal see since antiquity; the bishopric is now Greek Orthodox. The Roman Catholic Church claims it as a titular see.[15]

References

- Mogens Herman Hansen & Thomas Heine Nielsen (2004). "Thessaly and Adjacent Regions". An inventory of archaic and classical poleis. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 707. ISBN 0-19-814099-1.

- Strabo. Geographica. ix. p.438, xiv. p. 647. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Stephanus of Byzantium. Ethnica. s.v.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- Homer. Iliad. 2.729, 4.202.

- Strabo. Geographica. ix. p.437. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Strabo. Geographica. viii. p.374. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Leake Northern Greece, vol. iv. p. 285.

- Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). 18.56.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 32.13.

- Procopius, de Aedif. 4.3

- Hierocles. Synecdemus. 642.

- Leake Northern Greece, vol. i. p. 425, seq., vol. iv. p. 287.

- Richard Talbert, Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World, (ISBN 0-691-03169-X), Map 55.

- http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/d3t84.html

- Attribution