Trier Cathedral Treasury

The Trier Cathedral Treasury is a museum of Christian art and medieval art in Trier, Germany. The museum is owned by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Trier and is located inside the Cathedral of Trier. It contains some of the church's most valuable relics, reliquaries, liturgical vessels, ivories, manuscripts and other artistic objects. The history of the Trier church treasure goes back at least 800 years. In spite of heavy losses during the period of the Coalition Wars, it is one of the richest cathedral treasuries in Germany. With the cathedral it forms part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1]

Trierer Domschatzkammer | |

View of the Treasury. On the left the showcase with the Egbert shrine | |

| |

| Established | before 1200 |

|---|---|

| Location | Trier, Cathedral of Trier, Mustorstraße 2 |

| Type | museum of Christian art, museum of medieval art |

| Director | Jörg Michael Peters (custos since 2015) |

| Curator | Markus Groß-Morgen (in name of the Museum am Dom) |

| Website | www |

History

.jpg)

Early sources indicate that the cathedral's relics were kept in a separate room north of the east choir around 1200. Considering that the church is one of the oldest in Germany, it may be assumed that the treasure is even older. Tradition has it that Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great, who resided in Trier in the early 4th century, that gave the church some of its most valuable relics. In the late 10th century, under archbishop Egbert, Trier became a centre of the Ottonian Renaissance. Egbert's famous workshops produced metalwork and illuminated manuscripts, of which the cathedral acquired several.[2]

The treasure was moved to a larger room in 1480 in the so-called Badische Bau, part of the cloisters, where the treasury and the cathedral's archives are still housed. An increase in pilgrims led to the main relics and reliquaries being shown from 1512 until 1655 on a purpose-built platform in front of the western apse to the gathered pilgrims on the Domfreihof square.[3] Inventories dating from 1238, 1429 and 1776 provide detailed information on the history of the treasure, which for centuries remained largely intact, in spite of fires, sieges and pillaging. For the safety of the relics, several times (particularly during war), the main relics were transferred to Ehrenbreitstein, which had a safe haven maintained by the bishops of Trier.

The outbreak of the First Coalition War led in 1794 to the incorporation of Trier and most of the German Rhineland into the French First Republic. During this period a large portion of the treasure was lost, principally due to the heavy war taxes imposed on the cathedral chapter, which resulted in the melting down of gold and silver objects in order to pay the taxes. In 1792 alone, 399 kg of precious metal was handed in at the Trier Electoral mint. Only twelve objects made of precious metal survived. One of the many treasures that went missing was the so-called "monile of Saint Helena", a golden hanger with a relic of the True Cross, listed in the 1238 inventory.[4] The 10th-century "staff of Saint Peter", a masterpiece from the Egbert workshops, survived but ended up in the treasury of Limburg Cathedral.[5]

During the 19th and 20th century the treasure was partly restored through donations, loans, acquisitions from art dealers and commissions. The Byzantine Adventus Ivory that had been part of the cathedral treasure until 1792 was bought back in 1845.[6] In 1851, a 12th-century crosier was discovered in the grave of archbishop Heinrich II of Finstingen. Also in the 19th century, the periodical showing of the relics, especially the Holy Tunic, was resumed. In 1844 it was estimated that 600,000 pilgrims participated in the pilgrimage; in 1891 perhaps more than a million.[7]

At the end of the Second World War the main treasures from Trier, along with those from Aachen and Essen, were hidden in a deserted mine tunnel near Siegen. Here they were discovered by American troops in April 1945 and returned to Trier within a month. Other, less valuable objects ended up in the Marburg Central Collecting Point in Marburg, from where they were returned through the work of Walker Hancock (a member of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program).[8]

Collections

The Trier Cathedral treasure consists mainly of reliquaries, liturgical vessels, religious statues and reliefs, ivories and illuminated manuscripts. The objects date from the 3rd through the 20th century.

Relics and reliquaries

Four of the cathedral's main relics are not kept in the Treasury but elsewhere in the church. These are the Holy Tunic (in a separate chapel behind the main altar), the head reliquary of Saint Helena (in the east crypt), the reliquary shrine of Saint Maternus (in the central crypt) and the reliquary shrine of Saint Blaise and other saints (in the west crypt).[9]

The following are kept in the Treasury:

- the Egbert shrine, also referred to as the portable altar of Saint Andrew (German: Andreas-Tragaltar), a small reliquary chest from the late-10th-century Egbert workshops, with ivory plaques, enamels and precious stones, and a gold-plated foot on top (the first known 'speaking reliquary', in the shape of a body-part); containing relics of the apostle Andrew (the sole of his sandal), Saint Peter (some beard hair and part of his chain) and other relics mentioned below;[2]

- the Holy Nail, said to be a nail of the True Cross, found by Saint Helena and given to the church in Trier, according to tradition; contained in a precious reliquary, also from the Egbert workshops; previously held in the Egbert shrine;[10]

- the cup of Saint Helena, made of amethyst, dating from the 3rd/4th century, with 14th-century silver furnishing from Bohemia; also formerly held in the Egbert shrine;

- the silver arm reliquary of Saint Anne, dating from the 15th century, partly renewed in the 19th century.

Egbert shrine

Egbert shrine Holy Nail reliquary

Holy Nail reliquary Cup of Helena

Cup of Helena Saint Anne arm reliquary

Saint Anne arm reliquary

Liturgical objects

During its long history the cathedral collected numerous liturgical vessels, candlesticks, processional crosses and other objects used in mass or for administering the Holy Sacraments. Despite the losses in the late 18th and early 19th century, the following remain:

- a portable altar said to have belonged to Saint Willibrord; the Latin inscription in the 8th-century porphyry altar stone confirms this; it also informs that the altar contained relics of the True Cross and of Jesus' sudarium (it now contains relics of the Virgin Mary's dress); the ivories and silver reliefs were added later; until 1794 it was part of the treasury of the Liebfrauenkirche (Trier, 8th-14th c.);[11]

- a portable altar with relics (Trier?, 12th c.);

- the funeral chalice, paten and bishop's ring of Poppo von Babenberg, archbishop of Trier from 1016–47;

- the bronze thurible of Gozbert (Trier?, ca. 1100);

- a richly decorated silver thurible (Trier?, 12th c.);

- a coconut cup, probably used as a reliquary; originally from St. Gangolf's church (Trier?, ca. 1550-1600);

- various Romanesque Revival or Gothic Revival liturgical objects, several by the Aachen goldsmiths Reinhold Vasters, Martin Vogeno and August Witte, others by the Trier workshop of Brems-Varain.

12th-century portable altar

12th-century portable altar Grave goods bishop Poppo

Grave goods bishop Poppo Thurible of Gozbert

Thurible of Gozbert 16th-century coconut cup

16th-century coconut cup

Enamelling

The collection includes many enamels, including:

- the triptych of Saint Andrew (German: Andreas-Tragaltar), with a 16th-century silver-gilded statue of Saint Andrew in the central panel; the champlevé enamels on the side panels are possibly the work of Godefroid de Claire (Mosan, ca. 1160-70);

- a reliquary casket in champlevé with copper reliefs of saints (Limoges, late 12th c.);

- a processional cross in champlevé with a copper relief of Jesus (Limoges, late 12th c.);

- the crosier of Arnold II von Isenburg, archbishop of Trier from 1242-59 (Limoges, mid 13th c.);

- the crosier of Heinrich II von Finstingen, archbishop of Trier from 1260-86 (Limoges, mid 13th c.).

Saint Andrew triptych

Saint Andrew triptych Limoges reliquary casket

Limoges reliquary casket Limoges processional cross

Limoges processional cross Crosier of Arnold II

Crosier of Arnold II

Painting and sculpture

The cathedral in Trier owns many paintings, statues and reliefs, most of which can be found in the church, where they have a religious function. A few, mainly ivory carvings, are kept in the treasury:

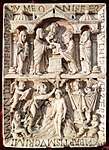

- the Byzantine Adventus Ivory, a Byzantine ivory relief of a procession with relics (Constantinople, 6th c.?);[6]

- an ivory relief with the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple and the Baptism of Jesus, part of a book cover of the Simeon Codex, formerly in St. Simeon's (Trier, ca. 1100);

- an ivory relief with the Annunciation, part of a book cover (Saxony, early 12th c.);

- a silver Madonna with Child in a halo of rays (Franz Thaddäeus Lang, Augsburg, 1725–30).

Adventus Ivory

Adventus Ivory Book cover Simeon Codex

Book cover Simeon Codex Saxonian book cover

Saxonian book cover Silver Madonna

Silver Madonna

Books and manuscripts

Only a few specimens from the collection of historical books and medieval manuscripts are on display in the treasury:

- Trier Evangeliary, Ms. 61 (Trier or Echternach, ca. 700-750);

- Simeon Codex or Codex Simeonis, Greek lectionary with ivory cover from St. Simeon's in Trier (10th/11th c.);

- Helmarshausen Evangeliarium, written in Helmarshausen Abbey by Theophilus Presbyter (Helmarshausen, ca. 1100);

- Pericope Book of Kuno II von Falkenstein, archbishop of Trier from 1362-88 (Trier, ca. 1380).

See also

- Cathedral of Trier

- Holy Tunic

- Trier Adventus Ivory

- Aachen Cathedral Treasury

- Essen Cathedral Treasury

References

- Roman Monuments, Cathedral of St Peter and Church of Our Lady in Trier on website whc.unesco.org.

- Martina Bagnoli, Holger A. Klein, C. Griffith Mann and James Robinson (ed.) (2011): Treasures of Heaven. Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europa, pp. 164-166. Exhibition catalogue of Cleveland Museum of Art, Walters Art Museum and British Museum, 2010-2011. Yale University Press, New Haven/London. ISBN 978-0-300-16827-3

- Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schmid: 'Sichere Verwahrung und öffentliche Zeigung', on website dominformation.de (in German)

- A.M. Koldeweij (1985): Der gude Sente Servas, p. 169. Maaslandse Monografieën #5. Van Gorcum, Assen/Maastricht. ISBN 90-232-2119-2 (in Dutch)

- Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schmid: 'Verluste und Neuerwerbungen', on website dominformation.de (in German)

- Bagnoli (2011), p. 38.

- Renate Kroos (1985): Der Schrein des heiligen Servatius in Maastricht und die vier zugehörigen Reliquiare in Brüssel, p. 396, note 149. Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, München. ISBN 3422007725 (in German)

- Herta Lepie and Georg Minkenberg (2010): The Cathedral Treasury of Aachen, p. 6. Museums and Treasuries in Europe, Volume 1. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg. ISBN 978-3-7954-2320-9

- Prof. Dr. Franz Ronig: Trier Cathedral, information brochure published by Trier Cathedral (2017).

- Bagnoli (2011), p. 82.

- Henk van Os (ed.) (2000): De weg naar de Hemel. Reliekverering in de Middeleeuwen, pp. 162-164. Exhibition catalogue Amsterdam and Utrecht. Uitgeverij De Prom, Baarn. ISBN 9068017322 (in Dutch)

![]()