Trial

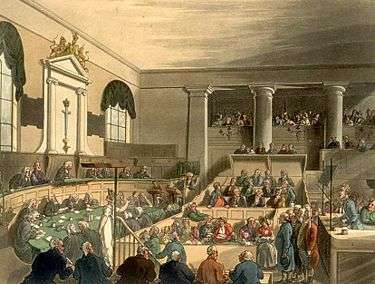

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, which may occur before a judge, jury, or other designated trier of fact, aims to achieve a resolution to their dispute.

| Criminal procedure |

|---|

| Criminal trials and convictions |

| Rights of the accused |

| Verdict |

|

| Sentencing |

|

| Post-sentencing |

|

| Related areas of law |

|

| Portals |

|

|

Types of trial divided by the finder of fact

Where the trial is held before a group of members of the community, it is called a jury trial. Where the trial is held solely before a judge, it is called a bench trial.

Hearings before administrative bodies may have many of the features of a trial before a court, but are typically not referred to as trials.

An appellate proceeding is also generally not deemed a trial, because such proceedings are usually restricted to review of the evidence presented before the trial court, and do not permit the introduction of new evidence.

Types of trial divided by the type of dispute

Trials can also be divided by the type of dispute at issue.

Criminal trial

A criminal trial is designed to resolve accusations brought (usually by a government) against a person accused of a crime. In common law systems, most criminal defendants are entitled to a trial held before a jury. Because the state is attempting to use its power to deprive the accused of life, liberty, or property, the rights of the accused afforded to criminal defendants are typically broad. The rules of criminal procedure provide rules for criminal trials.

Civil trial

A civil trial is generally held to settle lawsuits or civil claims—non-criminal disputes. In some countries, the government can both sue and be sued in a civil capacity. The rules of civil procedure provide rules for civil trials.

Administrative hearing and trial

Although administrative hearings are not ordinarily considered trials, they retain many elements found in more "formal" trial settings. When the dispute goes to judicial setting, it is called an administrative trial, to revise the administrative hearing, depending on the jurisdiction. The types of disputes handled in these hearings is governed by administrative law and auxiliarily by the civil trial law.

Labor trial

Labor law (also known as employment law) is the body of laws, administrative rulings, and precedents which address the legal rights of, and restrictions on, working people and their organizations. As such, it mediates many aspects of the relationship between trade unions, employers and employees. In Canada, employment laws related to unionized workplaces are differentiated from those relating to particular individuals. In most countries however, no such distinction is made. However, there are two broad categories of labour law. First, collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, employer and union. Second, individual labour law concerns employees' rights at work and through the contract for work. The labour movement has been instrumental in the enacting of laws protecting labour rights in the 19th and 20th centuries. Labour rights have been integral to the social and economic development since the industrial revolution.

Formats of trial

There are two primary systems for conducting a trial.

Adversarial system

In common law systems, an adversarial or accusatory approach is used to adjudicate guilt or innocence. The assumption is that the truth is more likely to emerge from the open contest between the prosecution and the defense in presenting the evidence and opposing legal arguments with a judge acting as a neutral referee and as the arbiter of the law. In several jurisdictions in more serious cases, there is a jury to determine the facts, although some common law jurisdictions have abolished the jury trial. This polarizes the issues, with each competitor acting in its own self-interest, and so presenting the facts and interpretations of the law in a deliberately biased way. The intention is that through a process of argument and counter-argument, examination-in-chief and cross-examination, each side will test the truthfulness, relevancy, and sufficiency of the opponent's evidence and arguments. To maintain fairness, there is a presumption of innocence, and the burden of proof lies on the prosecution. Critics of the system argue that the desire to win is more important than the search for truth. Further, the results are likely to be affected by structural inequalities. Those defendants with resources can afford to hire the best lawyers. Some trials are—or were—of a more summary nature, as certain questions of evidence were taken as resolved (see handhabend and backberend).

Inquisitorial system

In civil law legal systems, the responsibility for supervising the investigation by the police into whether a crime has been committed falls on an examining magistrate or judge who then conducts the trial. The assumption is that the truth is more likely to emerge from an impartial and exhaustive investigation both before and during the trial itself. The examining magistrate or judge acts as an inquisitor who directs the fact-gathering process by questioning witnesses, interrogating the suspect, and collecting other evidence. The lawyers who represent the interests of the State and the accused have a limited role to offer legal arguments and alternative interpretations to the facts that emerge during the process. All the interested parties are expected to co-operate in the investigation by answering the magistrate or judge's questions and, when asked, supplying all relevant evidence. The trial only takes place after all the evidence has been collected and the investigation is completed. Thus, most of the factual uncertainties will already be resolved, and the examining magistrate or judge will already have resolved that there is prima facie of guilt. Critics argue that the examining magistrate or judge has too much power in that he or she will both investigate and adjudicate on the merits of the case. Although lay assessors do sit as a form of jury to offer advice to the magistrate or judge at the conclusion of the trial, their role is subordinate. Further, because a professional has been in charge of all aspects of the case to the conclusion of the trial, there are fewer opportunities to appeal the conviction alleging some procedural error.

Mistrials

A judge may cancel a trial prior to the return of a verdict; legal parlance designates this as a mistrial.

A judge may declare a mistrial due to:

- The court determining that it lacks jurisdiction over a case.

- Evidence being admitted improperly, or new evidence that might seriously affect the outcome of the trial being discovered.

- Misconduct by a party, juror,[1] or an outside actor, if it prevents due process.

- A hung jury which cannot reach a verdict with the required degree of unanimity. In a criminal trial, if the jury is able to reach a verdict on some charges but not others, the defendant may be retried on the charges that led to the deadlock, at the discretion of the prosecution.

- Disqualification of a juror after the jury is empaneled, if no alternative juror is available and the litigants do not agree to proceed with the remaining jurors, or the remaining jurors not meeting the required number for a trial.

- Attempting to change a plea during an ongoing trial, which normally is not allowed.

A declaration of a mistrial generally means that a court must hold a retrial on the same subject.

Other kinds of trials

Some other kinds of processes for resolving conflicts are also expressed as trials. For example, the United States Constitution requires that, following the impeachment of the President, a judge, or another federal officer by the House of Representatives, the subject of the impeachment may only be removed from office by a trial in the Senate.

In earlier times disputes were often settled through a trial by ordeal, where parties would have to endure physical suffering in order to prove their righteousness; or through a trial by combat, in which the winner of a physical fight was deemed righteous in their cause.

References

- St. Eve, Amy; Michael Zuckerman (2012). "Ensuring an Impartial Jury in the Age of Social Media" (PDF). Duke Law & Technology Review. 11.