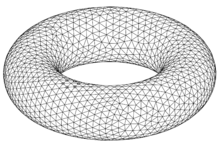

Triangulation (topology)

In mathematics, topology generalizes the notion of triangulation in a natural way as follows:

- A triangulation of a topological space X is a simplicial complex K, homeomorphic to X, together with a homeomorphism h: K → X.

Triangulation is useful in determining the properties of a topological space. For example, one can compute homology and cohomology groups of a triangulated space using simplicial homology and cohomology theories instead of more complicated homology and cohomology theories.

Piecewise linear structures

For topological manifolds, there is a slightly stronger notion of triangulation: a piecewise-linear triangulation (sometimes just called a triangulation) is a triangulation with the extra property – defined for dimensions 0, 1, 2, . . . inductively – that the link of any simplex is a piecewise-linear sphere. The link of a simplex s in a simplicial complex K is a subcomplex of K consisting of the simplices t that are disjoint from s and such that both s and t are faces of some higher-dimensional simplex in K. For instance, in a two-dimensional piecewise-linear manifold formed by a set of vertices, edges, and triangles, the link of a vertex s consists of the cycle of vertices and edges surrounding s: if t is a vertex in this cycle, t and s are both endpoints of an edge of K, and if t is an edge in this cycle, it and s are both faces of a triangle of K. This cycle is homeomorphic to a circle, which is a 1-dimensional sphere. But in this article the word "triangulation" is just used to mean homeomorphic to a simplicial complex.

For manifolds of dimension at most 4, any triangulation of a manifold is a piecewise linear triangulation: In any simplicial complex homeomorphic to a manifold, the link of any simplex can only be homeomorphic to a sphere. But in dimension n ≥ 5 the (n − 3)-fold suspension of the Poincaré sphere is a topological manifold (homeomorphic to the n-sphere) with a triangulation that is not piecewise-linear: it has a simplex whose link is the Poincaré sphere, a three-dimensional manifold that is not homeomorphic to a sphere. This is the double suspension theorem, due to R.D. Edwards in the 1970s.[1][2][3]

The question of which manifolds have piecewise-linear triangulations has led to much research in topology. Differentiable manifolds (Stewart Cairns, J. H. C. Whitehead, L. E. J. Brouwer, Hans Freudenthal, James Munkres),[4][5] and subanalytic sets (Heisuke Hironaka and Robert Hardt) admit a piecewise-linear triangulation, technically by passing via the PDIFF category. Topological manifolds of dimensions 2 and 3 are always triangulable by an essentially unique triangulation (up to piecewise-linear equivalence); this was proved for surfaces by Tibor Radó in the 1920s and for three-manifolds by Edwin E. Moise and R. H. Bing in the 1950s, with later simplifications by Peter Shalen.[6][7] As shown independently by James Munkres, Steve Smale and J. H. C. Whitehead,[8][9] each of these manifolds admits a smooth structure, unique up to diffeomorphism.[7][10] In dimension 4, however, the E8 manifold does not admit a triangulation, and some compact 4-manifolds have an infinite number of triangulations, all piecewise-linear inequivalent. In dimension greater than 4, Rob Kirby and Larry Siebenmann constructed manifolds that do not have piecewise-linear triangulations (see Hauptvermutung). Further, Ciprian Manolescu proved that there exist compact manifolds of dimension 5 (and hence of every dimension greater than 5) that are not homeomorphic to a simplicial complex, i.e., that do not admit a triangulation.[11]

Explicit methods of triangulation

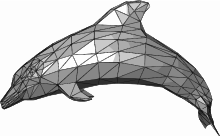

An important special case of topological triangulation is that of two-dimensional surfaces, or closed 2-manifolds. There is a standard proof that smooth compact surfaces can be triangulated.[12] Indeed, if the surface is given a Riemannian metric, each point x is contained inside a small convex geodesic triangle lying inside a normal ball with centre x. The interiors of finitely many of the triangles will cover the surface; since edges of different triangles either coincide or intersect transversally, this finite set of triangles can be used iteratively to construct a triangulation.

Another simple procedure for triangulating differentiable manifolds was given by Hassler Whitney in 1957,[13] based on his embedding theorem. In fact, if X is a closed n-submanifold of Rm, subdivide a cubical lattice in Rm into simplices to give a triangulation of Rm. By taking the mesh of the lattice small enough and slightly moving finitely many of the vertices, the triangulation will be in general position with respect to X: thus no simplices of dimension < s = m − n intersect X and each s-simplex intersecting X

- does so in exactly one interior point;

- makes a strictly positive angle with the tangent plane;

- lies wholly inside some tubular neighbourhood of X.

These points of intersection and their barycentres (corresponding to higher dimensional simplices intersecting X) generate an n-dimensional simplicial subcomplex in Rm, lying wholly inside the tubular neighbourhood. The triangulation is given by the projection of this simplicial complex onto X.

Graphs on surfaces

A Whitney triangulation or clean triangulation of a surface is an embedding of a graph onto the surface in such a way that the faces of the embedding are exactly the cliques of the graph.[14][15][16] Equivalently, every face is a triangle, every triangle is a face, and the graph is not itself a clique. The clique complex of the graph is then homeomorphic to the surface. The 1-skeletons of Whitney triangulations are exactly the locally cyclic graphs other than K4.

References

- Edwards, Robert D. (2006), Suspensions of Homology Spheres, arXiv:math/0610573 (reprint of private, unpublished manuscripts from the 1970's)

- Edwards, R. D. (1980), "The topology of manifolds and cell-like maps", in Lehto, O. (ed.), Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, Helsinki, 1978, Acad. Sci. Fenn, pp. 111–127

- Cannon, J. W. (1978), "Σ2 H3 = S5 / G", Rocky Mountain J. Math., 8: 527–532

- Whitehead, J. H. C. (October 1940), "On C1-Complexes", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series, 41 (4): 809–824, doi:10.2307/1968861, JSTOR 1968861

- Munkres, James (1966), Elementary Differential Topology, revised edition, Annals of Mathematics Studies 54, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-09093-9

- Moise, Edwin (1977), Geometric Topology in Dimensions 2 and 3, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90220-1

- Thurston, William (1997), Three-Dimensional Geometry and Topology, Vol. I, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08304-5

- Munkres, James (1960), "Obstructions to the smoothing of piecewise-differentiable homeomorphisms", Annals of Mathematics, 72 (3): 521–554, doi:10.2307/1970228, JSTOR 1970228

- Whitehead, J.H.C. (1961), "Manifolds with Transverse Fields in Euclidean Space", The Annals of Mathematics, 73 (1): 154–212, doi:10.2307/1970286, JSTOR 1970286

- Milnor, John W. (2007), Collected Works Vol. III, Differential Topology, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-4230-7

- Manolescu, Ciprian (2016), "Pin(2)-equivariant Seiberg–Witten Floer homology and the Triangulation Conjecture", J. Amer. Math. Soc., 29: 147–176, arXiv:1303.2354, doi:10.1090/jams829

- Jost, Jürgen (1997), Compact Riemann Surfaces, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-53334-6

- Whitney, Hassler (1957), Geometric integration theory, Princeton University Press, pp. 124–135

- Hartsfeld, N.; Ringel, G. (1991), "Clean triangulations", Combinatorica, 11 (2): 145–155, doi:10.1007/BF01206358

- Larrión, F.; Neumann-Lara, V.; Pizaña, M. A. (2002), "Whitney triangulations, local girth and iterated clique graphs", Discrete Mathematics, 258: 123–135, doi:10.1016/S0012-365X(02)00266-2

- Malnič, Aleksander; Mohar, Bojan (1992), "Generating locally cyclic triangulations of surfaces", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 56 (2): 147–164, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(92)90015-P

Further reading

- Dieudonné, Jean (1989), A History of Algebraic and Differential Topology, 1900–1960, Birkhäuser, ISBN 0-8176-3388-X