Trial of the Six

The Trial of the Six (Greek: Δίκη των Έξι, Díki ton Éxi) or the Execution of the Six was the trial for treason, in late 1922, of the anti-venizelists officials held responsible for the Greek military defeat in Asia Minor. The trial culminated in the death sentence and execution of six of the nine defendants.

Background

On September 9, 1922, Turkish military and guerilla forces entered the city of İzmir in Asia Minor, which was previously mandated to Greece by the Treaty of Sèvres. Hundreds of thousands of Greek residents from Asia Minor fled to Smyrna seeking transportation across the sea to escape the advancing Turks. The pro-royalist government in Athens lost control of the situation and could only watch as the events unfolded. The retreating Greek "Army of the East" abandoned Smyrna on September 8, the day before the Turkish Army moved in. Transportation arrived late and in too small numbers relative to the number of people trying to flee, resulting in chaos and panic. In a chaotic and bloody battle which would come to be known as the "Asia Minor Catastrophe", Greece lost the Asia Minor land mandate to Turkey. Those who survived the bloody evacuation of the area would spend the rest of their lives as refugees.(Greek: Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή, Mikrasiatiki Katastrophi).

Coup

Anti-royalist factions, seizing the moment of public outrage, moved against the Pro-Royalist government and a military coup d'état unfolded in Athens and the Aegean Islands. Backed by an angry civil response to the defeat in the fields of battle, on September 11, 1922, Colonels Nikolaos Plastiras and Stylianos Gonatas formed a "Revolutionary Committee" that demanded the abdication of King Constantine (considered responsible for the defeat). They demanded as well the resignation of the royalist government, and the punishment of those responsible for the military disaster. The coup was aided by venizelist General Theodoros Pangalos, then stationed in Athens. Backed by massive demonstrations in the capital, the coup was successful: two days later, on September 13, when Plastiras and Gonatas disembarked in the port of Laurium with the military units they commanded, King Constantine abdicated in favour of his first-born son, George and sailed for Sicily, never to return. The government ministers were arrested and the new king consented to a new administration, one favorable to the coup.

General Nikolaos Plastiras

General Nikolaos Plastiras

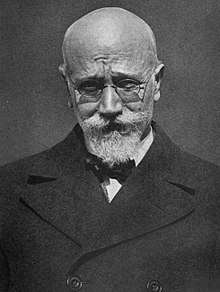

Eleftherios Venizelos was placed as exterior representative of Greece

Eleftherios Venizelos was placed as exterior representative of Greece

Trial

On October 12, 1922, the junta constituted an "extraordinary military tribunal", which convened on October 31 and carried out a two-week-long trial in which the five most senior members of the overthrown administration (Dimitrios Gounaris, Georgios Baltatzis (el), Nikolaos Stratos, Nikolaos Theotokis (el), and Petros Protopapadakis) and General Georgios Hatzianestis (last commander-in-chief of the Asia Minor campaign) were tried for high treason, convicted, and sentenced to death. They were executed a few hours after the verdict was handed down, and before its publication on November 15, 1922. According to the decision, the six with their support for the return of exiled Constantine to the throne and with their decisions during the war against Kemal, damaged the national interests and strained the relations with the Allies, leading the country to the defeat. The decision was previously taken to the office of Plastiras, "leader of the revolution" to sign. He is reported to have read it and replaced the phrase "in the name of King George II" with "in the name of the Revolution".

Two defendants, Admiral Michail Goudas (el) and General Xenophon Stratigos, received a life imprisonment sentence. The ex-king's brother, Prince Andrew, also a senior commanding officer in the failed campaign, had been indicted as well but was in Corfu at the time. He was arrested, transported to Athens, tried by the same tribunal a few days later, and found guilty of the same crimes, but was recognised as being "completely lacking in military command experience", a mitigating of ironic circumstance. He was sentenced to death first and then banishment from Greece for life. The prince and his family (which included his infant son – carried in a vegetable wooded cot – Prince Philip, later the Duke of Edinburgh) were evacuated on a British warship on December 4, leaving Corfu island for Brindisi.

Punishments

Dimitrios Gounaris, death

Dimitrios Gounaris, death Petros Protopapadakis, death

Petros Protopapadakis, death Nikolaos Stratos, death

Nikolaos Stratos, death- General Georgios Hatzianestis, death

Georgios Baltatzis, death

Georgios Baltatzis, death Prince Andrew, death (finally life exiled)

Prince Andrew, death (finally life exiled) Xenophon Stratigos, life imprisonment

Xenophon Stratigos, life imprisonment

Aftermath

The embassies of Sweden, Netherlands and United Kingdom objected and tried to cancel the punishments without success. After the executions, and in response, the United Kingdom withdrew its ambassador to Greece for some time.

The executions were a kind of shock for the Greek conservatives, while they exacerbated the conflict between the royalists and the liberals the next decades, at least until the establishment of the 4th of August Regime.

In 1932, during a speech in parliament, Prime Minister Venizelos supported that the victims were indeed not guilty "for treason", but he couldn't and wouldn't condemn any revolutionary officers of the military tribune, because they acted in patriotic and virtuous way.

Reversal

In 2010, Greek courts reversed the convictions for high treason of the six after former prime minister Petros Protopapadakis’ grandson was able to present new evidence in court that had been absent in the 1922 trial and which was deemed sufficient to exonerate them. In summary, it was believed that the six had been scapegoats to appease public anger at the humiliation that the Greeks had suffered in the Asia Minor Catastrophe and that the six, who had no desire to see Greek forces defeated, had been in reality just victims of circumstances they were unable to control. The lawsuit to overturn the previous convictions for high treason was made in an effort to rewrite school textbooks that had been unfair to the six.[1]

References

- Nicholas Paphitis (October 20, 2010). "Greek court reverses traitor convictions from 1922". TheStar. Associated Press. Retrieved August 31, 2017.