Charles-Joseph Traviès de Villers

Charles-Joseph Traviès de Villers, also known simply as Traviès, (21 February 1804 – 13 August 1859) was a Swiss-born French painter, lithographer, and caricaturist whose work appeared regularly in Le Charivari and La Caricature. His Panthéon Musical was one of the most famous and widely reproduced musical caricatures of the 19th century. His younger brother was the painter and illustrator Édouard Traviès.[2][3]

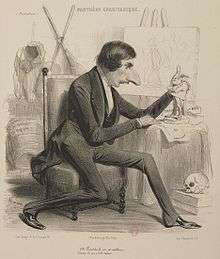

Charles-Joseph Traviès de Villers | |

|---|---|

Caricature of Traviès by Benjamin Roubaud[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Born | 21 February 1804 Wülflingen, Swtizerland |

| Died | 13 August 1859 (aged 55) Paris, France |

| Occupation |

|

Life and career

Traviès was born in Wülflingen (now a district in the Swiss city of Winterthur) although he later became a naturalised French citizen. His father was an engraver of English descent. His mother was from a French family and a descendant of the Marquis de Villers. He studied art in Strasbourg and later under François Joseph Heim at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. When he was a young man, a series of financial misfortunes left his parents in poverty, and he became their sole support. He began his career producing portraits and genre paintings and made his debut at the Paris Salon in 1823. He also turned his hand to producing designs for wallpaper and printed fabrics.

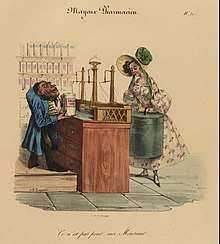

By the late 1820s he had become a popular caricaturist enjoying particular success with his collections Tableau de Paris and Galerie des Épicuriens. He then joined Charles Philipon's satirical magazines La Caricature and La Charivari where he was to become one of their most prolific caricaturists.[4][5][6] Both magazines were highly critical of the July Monarchy and its king, Louis Philippe, whom they mercilessly caricatured. His most famous creation during this period was the character "Mayeaux" (sometimes spelled "Mahieux") a hunchback who came to represent all the faults and foibles of the bourgeoisie who were the principle supporters of Louis Philippe. The character, which first appeared in the pages of La Caricature in 1831, was the inspiration for several other satirists including Daumier, Grandville, and Honoré de Balzac. Using pseudonyms, Balzac wrote two articles on Mayeux's adventures for La Caricature—"M. Mahieux en société" and "M. Mahieux au bal de l'Opéra".

During this time Traviès also became involved in early socialist movements, an interest which he maintained throughout his life. He was first attracted to Saint-Simonianism and then to the ideas of Simon Ganneau, becoming a follower of Ganneau's sect Evadisme which focused heavily on equality of the sexes. In his later years he would become increasingly attracted to the utopian socialism of Charles Fourier and Fourier's disciple Jean Journet. He also carried out lengthy correspondence with Flora Tristan and François Ponsard, a poet and playwright of socialist leanings.[4][7]

Following the assassination attempt on Louis Philippe in July 1835, a law was passed on 9 September 1835 forbidding political caricatures and articles critical of the king. In light of the subsequent fines and imprisonments imposed on the press for violations of this law, Traviès, like many of his colleagues, turned his attention to satirizing French customs and culture. He also provided illustrations for Balzac's La Comédie humaine and Eugène Sue's Les Mystères de Paris as well as producing many depictions of the Parisian poor and their daily life.[4][5][1][lower-alpha 2] Baudelaire, who was an admirer of his work, including these later pieces, wrote of Traviès:

He is the prince of the unfortunate. His muse is a nymph of the suburbs, pale and melancholy. [...] Traviès has a deep feeling for the joys and sorrows of the common people. He knows the scoundrel thoroughly, and he loves him with tender charity. For this reason his Scènes Bachiques will remain a remarkable work.[9]

When Baudelaire wrote these words in 1857 he observed that Traviès had been inexplicably "missing from the scene" for quite a while. After 1845 Traviès had worked more and more sporadically. The last fourteen years of his life were marked by depression and illness. However, he exhibited portraits in the 1848 and 1855 Paris Salons and finally managed to complete his religious painting Christ et la Samaritaine which was exhibited in the 1853 Salon and bought by the French government. He died in his Paris apartment on 13 August 1859 at the age of 55. According to contemporary obituaries, he died in poverty lying on a straw bed.[10][5][6]

Works

Portraits and paintings

Armand Barbès en Prison

Armand Barbès en Prison Elisa Julian

Elisa Julian.jpg) Christ et la Samaritaine (detail)

Christ et la Samaritaine (detail)

Armand Barbès en Prison, drawn by Traviès in 1835, is the only known portrayal of Armand Barbès in prison. It depicts him alone in his cell in Sainte-Pélagie where he was held from 1834 to 1835, the first of his many imprisonments. The drawing conveys a sense of melancholy and isolation with deep shadows and only the subject's face illuminated.[11] Traviès's lithograph portrait of the opera singer Elisa Julian, published in the journal La Sylphide in 1840 and exhibited at the Paris Salons of 1848 and 1855, was particularly admired by the writer Alfred Deberle. During the late 1830s Traviès also produced lithograph portraits of the composer Ferdinand Hérold and statesman Dupont de l'Eure as well as Galerie des Illustrations Scientifiques, a series of portraits of prominent French doctors and scientists which were published in Charivari and separately as prints by Maison Aubert.[8]

The art critic Champfleury, who knew Traviès in his later years, described his studio as filled with unfinished religious paintings by a painter who appeared to have lost his confidence. He finally completed his Christ et la Samaritaine (Christ and the Samaritan woman) after working on it for over 14 years. Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1853 and bought by the French government, it now hangs in the parish church of Saint-Gilles, Gard. In 1975 it was declared a monument historique as one of the few known examples of a Traviès oil painting.[12][13] Another unsigned oil painting c. 1840 depicting the cabaret at Café des Aveugles is attributed to Traviès by the Musée Carnavalet, although the art historian Claude Ferment has disputed the attribution as almost certainly an error. The painting was shown in the Paris Pavilion at the Exposition internationale de Liège in 1930.[14][15]

Notes

References

- Farwell, Beatrice and Henning, Robert (1989). The Charged Image: French Lithographic Caricature, 1816-1848, p. 27. Santa Barbara Museum of Art. ISBN 0899510752

- Bellier de La Chavignerie, Émile and Auvray, Louis (1885). Dictionnaire général des artistes de l'École française depuis l'origine des arts du dessin jusqu'à nos jours, Vol. 2, p. 588. Librairie Renouard (in French)

- Weinstock, Herbert (1963). Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris, and Vienna in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, p. 205. Octagon Books (reprint). ISBN 0374983372

- De Ruvo, Francesca and Mazzaro, Alessandramonica (2016). Un secolo di satira, pp. 130–133. Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa. ISBN 9788896055762 (in Italian)

- Deberle, Alfred (15 September 1859). "C. J. Traviès". L'Orchestre, p. 2 (in French)

- Vapereau, Gustave (1870). "Traviès de Villers (Charles-Joseph)". Dictionnaire universel des contemporains, Vol. 2, p. 1682. Hachette et Cie (in French)

- Kerr, David S. (2000). Caricature and French Political Culture 1830-1848, p. 40. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0191543047

- Beraldi, Henri (1885). Les graveurs du 19e siècle; guide de l'amateur d'estampes modernes, Vol. XII, pp. 142-153. L. Conquet (in French)

- Baudelaire, Charles (1 October 1857). "Quelques caricaturistes français". Le Présent, pp. 93–95 (in French)

- "A. D." (29 September 1860). "Causerie artistique". La Lumière, 10e Année, No 39, pp. 154–155 (in French).

- Albigès, Luce-Marie (November 2004). "Armand Barbès prisonnier au Mont-Saint-Michel (1839-1843)". L'Histoire par l'image. Retrieved 26 May 2017 (in French).

- Champfleury (1885). Histoire de la caricature moderne, pp. 219–238. E. Dentu (in French)

- Ministère de la Culture (2013). Monuments historiques: le Christ et la Samaritaine (Reference PM30000875). Retrieved 26 May 2017 (in French).

- Ferment, Claude (February 1982). "Le Caricaturiste Travies: La Vie et l'oeuvre d'un 'Prince du Guignon'" Gazette des Beaux-Arts pp. 63-78

- Musée Carnavalet. Le Café des Aveugles, au Palais-Royal. Retrieved 26 May 2017 (in French).

Further reading

- Maurice, Arthur Bartlett, and Cooper, Frederic Taber (1904). History of the Nineteenth Century in Caricature, pp. 91–93. Dodd, Mead and Co.

External links

- Works by Charles-Joseph Traviès de Villers in the Paris Musées collections (in French)

- Works by Charles-Joseph Traviès de Villers in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco collections