Tranche

In structured finance, a tranche is one of a number of related securities offered as part of the same transaction. In the financial sense of the word, each bond is a different slice of the deal's risk. Transaction documentation (see indenture) usually defines the tranches as different "classes" of notes, each identified by letter (e.g., the Class A, Class B, Class C securities) with different bond credit ratings.

| Financial markets |

|---|

|

| Bond market |

| Stock market |

| Other markets |

| Over-the-counter (off-exchange) |

| Trading |

| Related areas |

The term tranche is used in fields of finance other than structured finance (such as in straight lending, where multi-tranche loans are commonplace), but the term's use in structured finance may be singled out as particularly important. Use of "tranche" as a verb is limited almost exclusively to this field.

The word tranche is French for 'slice', 'section', 'series', or 'portion', and is a cognate of the English 'trench' ('ditch').

How tranching works

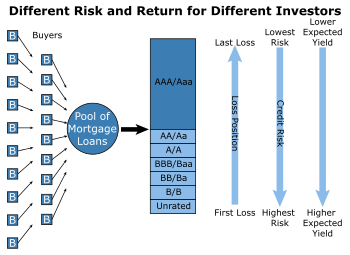

All the tranches together make up what is referred to as the deal's capital structure or liability structure. They are generally paid sequentially from the most senior to most subordinate (and generally unsecured), although certain tranches with the same security may be paid pari passu. The more senior rated tranches generally have higher bond credit ratings (ratings) than the lower rated tranches. For example, senior tranches may be rated AAA, AA or A, while a junior, unsecured tranche may be rated BB. However, ratings can fluctuate after the debt is issued, and even senior tranches could be rated below investment grade (less than BBB). The deal's indenture (its governing legal document) usually details the payment of the tranches in a section often referred to as the waterfall (because the monies flow down).

Tranches with a first lien on the assets of the asset pool are referred to as senior tranches and are generally safer investments. Typical investors of these types of securities tend to be conduits, insurance companies, pension funds and other risk averse investors.

Tranches with either a second lien or no lien are often referred to as "junior notes". These are more risky investments because they are not secured by specific assets. The natural buyers of these securities tend to be hedge funds and other investors seeking higher risk/return profiles.

"Market information also suggests that the more junior tranches of structured products are often bought by specialist credit investors, while the senior tranches appear to be more attractive for a broader, less specialised investor community".[1] Here is a simplified example to demonstrate the principle:

Example

- A bank transfers risk in its loan portfolio by entering into a default swap with a ring-fenced special purpose vehicle (SPV).

- The SPV buys gilts (UK government bonds).

- The SPV sells 4 tranches of credit linked notes with a waterfall structure whereby:

- Tranche D absorbs the first 25% of losses on the portfolio, and is the most risky.

- Tranche C absorbs the next 25% of losses

- Tranche B the next 25%

- Tranche A the final 25%, is the least risky.

- Tranches A, B and C are sold to outside investors.

- Tranche D is bought by the bank itself.

Benefits

Tranching offers the following benefits:

- Tranches allow for the "ability to create one or more classes of securities whose rating is higher than the average rating of the underlying collateral asset pool or to generate rated securities from a pool of unrated assets".[1] "This is accomplished through the use of credit support specified within the transaction structure to create securities with different risk-return profiles. The equity/first-loss tranche absorbs initial losses, followed by the mezzanine tranches which absorb some additional losses, again followed by more senior tranches. Thus, due to the credit support resulting from tranching, the most senior claims are expected to be insulated - except in particularly adverse circumstances - from default risk of the underlying asset pool through the absorption of losses by the more junior claims."[2]

- Tranching can be very helpful in many different circumstances. For those investors that have to invest in highly rated securities, they are able to gain "exposure to asset classes, such as leveraged loans, whose performance across the business cycle may differ from that of other eligible assets."[1] So essentially it allows investors to further diversify their portfolio.

Risks

Tranching poses the following risks:

- Tranching can add complexity to deals. Beyond the challenges posed by estimation of the asset pool's loss distribution, tranching requires detailed, deal-specific documentation to ensure that the desired characteristics, such as the seniority ordering the various tranches, will be delivered under all plausible scenarios. In addition, complexity may be further increased by the need to account for the involvement of asset managers and other third parties, whose own incentives to act in the interest of some investor classes at the expense of others may need to be balanced.

- With increased complexity, less sophisticated investors have a harder time understanding them and thus are less able to make informed investment decisions. One must be very careful investing in structured products. As shown above, tranches from the same offering have different risk, reward, and/or maturity characteristics.

- Modeling the performance of tranched transactions based on historical performance may have led to the over-rating (by ratings agencies) and underestimation of risks (by end investors) of asset-backed securities with high-yield debt as their underlying assets. These factors have come to light in the subprime mortgage crisis.

- In case of default, different tranches may have conflicting goals, which can lead to expensive and time-consuming lawsuits, called tranche warfare (punning on trench warfare).[3] Further, these goals may not be aligned with those of the structure as a whole or of any borrower—in formal language, no agent is acting as a fiduciary. For example, it may be in the interests of some tranches to foreclose on a defaulted mortgage, while it would be in the interests of other tranches (and the structure as the whole) to modify the mortgage. In the words of structuring pioneer Lewis Ranieri:[4]

The cardinal principle in the mortgage crisis is a very old one. You are almost always better off restructuring a loan in a crisis with a borrower than going to a foreclosure. In the past that was never at issue because the loan was always in the hands of someone acting as a fiduciary. The bank, or someone like a bank owned them, and they always exercised their best judgement and their interest. The problem now with the size of securitization and so many loans are not in the hands of a portfolio lender but in a security where structurally nobody is acting as the fiduciary.

See also

| Look up tranche in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Pooled investment

- Privatization

- Thomson Financial League Tables

References

- I. Fender, J. Mitchell "Structured finance: complexity, risk and the use of ratings" BIS Quarterly Review, June 2005

- "The role of ratings in structured finance: issues and implications" Committee on the Global Financial System, January 2005

- The mother of all (RMBS) tranche warfare, Financial Times Alphaville, Tracy Alloway, Oct 11 2010

- The Financial Innovation That Wasn’t. Rortybomb, Mike Rorty, transcript of Milken Institute Conference, May 2008