Trams in Perugia

The Perugia Tramway (Italian: Tranvia di Perugia) opened in 1899, which was the same year as that in which electric street lighting came to the city. The purpose of the Tramway was to link the historical city centre with the city's railway station, some 3 km away down the hill.[1]

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Perugia, Umbria, Italy |

| Number of lines | 1 |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | 1899 |

| Ended operation | 1943 |

| Operator(s) | Società Anonima Elettricità Umbra (1899-1929) Società Unione Esercizi Elettrici (1929-1943) |

| Number of vehicles | 8 powered trams 4 unpowered tram trailers 1 coal trailer 2 mail trailers |

| Technical | |

| System length | 4.24 km (2.63 mi) (after 1932 3.9 km (2.4 mi)) |

| Track gauge | 1 Meter |

| Electrification | 550 V DC overhead lines |

The Mussolini government became very keen on trolleybuses, and in October 1943 Perugia's tramway was replaced with a Trolleybus service[1] which would last till 1975.

History

Inspiration was drawn from the experience of Italy's first electrically powered tramcar introduced on the (originally horse-powered) Florence-Fiesole line earlier in the 1890s. A contract for the construction of the Perugia tramline was awarded on 10 April 1899 to the "Napoleone Pimpinelli" company, which executed the work under the supervision of Berlin based Siemens & Halske.[1] The tramway construction was part of a larger project of urban modernisation which also included an aqueduct and an electricity supply network. Work progressed speedily and the tramway was formally opened less than six months later, on 20 September 1899, in the presence of the minister and future prime minister Antonio Salandra.[1] At the time when the tramcars were delivered to the city's main station they had to be delivered to the storage location using ox carts, and until 1901 the service provided was intermittent because of constant interruptions to the electric power supply.[2]

The service was operated by Società Anonima Elettricità Umbra (SAEU), a company operated by the German Siemens-Shukert group: SAEU was also the company that had taken care of the city's switch-over from gas lighting to electric lighting. The new tramway was not universally welcomed, since the city centre retains its Medieval street plan, which meant that even on the central Corso Vannucci (street) where tram rails were laid, they sometimes passed unnervingly close to peoples' shops and homes. On the other hand, the hill-top location of the city centre meant that children, periodically interrupted by a passing tram, could enjoy rolling and racing bowling balls down the tracks.[2]

The first timetables gave a journey time between the station and the city centre, and this proved sustainable not withstanding some vocal protests about the perceived danger the stability of the city's buildings from the vibrations of the trams rattling past.[3] There were also sometimes journeys involving good wagon from the national rail service being towed into the centre by the municipal trams. (It was not possible for standard Italian railway locomotives to operate on the tramway because the gauge of the tramway was narrower than the national railway system's standard gauge.[1])

In 1929[4] responsibility for operating the tramway transferred from the SAEU to the Unione Esercizi Elettrici (UNES), a Rome based operation which by now was itself under the control of the IRI, the Italian state controlled holding company. In 1932 tram rails were removed from the northern end of the tramway, reducing its overall length by approximately 500 meters, clearing trams from the Corso Vannucci, and transferring the city centre terminus point from the Piazza Danti to the Piazza Italia.[1]

Ultimate ownership moved south in 1939 when the Unione Esercizi Elettrici (UNES) was sold to the Naples based Società Meridionale di Elettricità (SME / Southern Electricity Company). It was not till 1943, however, that an urban transformation project that had been under discussion for some time came to fruition when, on 28 October, trolley buses replaced trams on the route of the former tramway.[1]

Characteristics

The tramway's defining characteristics were imposed by the lay-out of the streets and by the city's topography. Over a total length of 4.24 km (2.63 mi) the route covered a change in altitude of 175.9 m (577 ft), giving rise to an average gradient of 0.42%, which peaked at 0.72% where the line passed the Church of Sant'Ercolano. The street-plan called for some sharp changes of direction which made it necessary to employ a relatively narrow 1 Meter gauge, using Phoenix 42.8 kg/m rails with a tight minimum turn-radius of 20 meters.[1]

The tramway collected electricity from 550 volt overhead wires.[1]

Tramcars

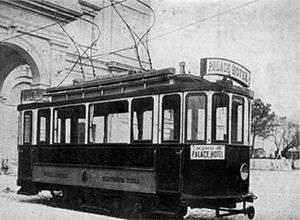

Eight twin axle electrically powered tramcars were acquired for the network from the Savigiano engineering company, and fitted out appropriately. They were 7.9 m (26 ft) long and 2 m (6.6 ft) wide, with 24 seats. Six of the eight are described as incorporating a baggage trunk (Con bagagliaio laterale). Each tramcar was powered by two 26 kW Siemens motors. One of the eight tramcars was reserved for the exclusive use of the city's "Hotel Palace".[1]

There were four unpowered trailer-trams, each with two axles and 30 seats. Two of these had an open balcony at each end.[1]

There was also an open high sided wagon used to convey coal to the city's power station and there were two lighter trucks used for transporting mail.[1]

The route

Before the line was shortened in 1932 the city centre terminus of the tramline was at the Piazza Danti, in front of the cathedral.[2] Until the tramline was installed the Piazza was known locally as the "Piazza del Papa" ("Pope Piazza"), which was a reference to the bronze statue of Pope Julius III by Vincenzo Danti that had to be repositioned to create space for the electric tram.

From here the line followed the corso Vannucci to the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II, which marked the start of a long descent along the viale Carlo Alberto (a street which has subsequently been renamed "viale Indipendenza"), passing the "Three Arches" and continuing to the Piazza d'Armi and passing close to the Porta Nuova. The route then followed the main road towards Cortona before turning south, ending up outside the main station.[1]

A branch line led to the city power plant in the via XIV Settembre, and was used for delivering coal.

References

- Adriano Cioci (2001). La tranvia di Perugia. Le strade ferrate in Umbria. Volumnia Editrice, Perugia. ISBN 88-85330-92-4.

- "Il Tram a Perugia". This source is in essence an on-line display of historical photographs of Perugia produced by Giacomo Santucci (1922-2006). "Old Perugia", il sito dedicato a Immagini della Perugia di un tempo. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Relazione della Commissione nominata dal Municipio di Perugia per constatare, se il Movimento del tram nel Corso Vannucci abbia arrecato e possa arrecare danno ai dipinti delle Sale dell'antico collegio del cambio Perugia report by Giuseppe Bellucci, Perugia, 1905.

- Marco Penchini, Nascita e sviluppo del servizio di elettricità a Perugia: la Società Anonima Elettricità Umbra (1899-1929), in Uomini, economie, culture. Saggi in memoria di Giampaolo Gallo, a cura di Renato Covino, Alberto Grohmann, Luciano Tosi, Esi, Napoli, 1997, vol. II, pp. 217-241. Il