Trajan's Wall

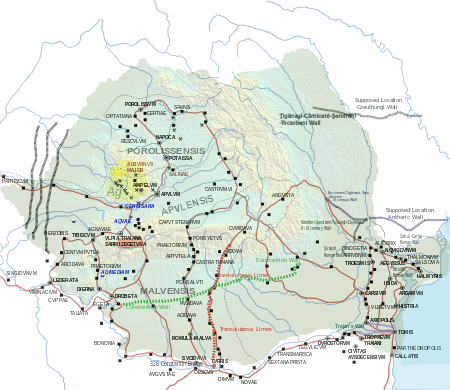

Trajan's Wall (Valul lui Traian in Romanian) is the name used for several linear earthen fortifications (valla) found across Eastern Europe, in Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine. Contrary to the name and popular belief, the ramparts were not built by Romans during Trajan's reign, but during other imperial periods. Furthermore, the association with the Roman Emperor may be a recent scholarly invention, only entering the imagination of the locals with the national awakening of the 19th century. Medieval Moldavian documents referred to the earthworks as Troian, likely in reference to a mythological hero in the Romanian and Slavic folklore.[1] The other major earthen fortification in Romania, Brazda lui Novac (Novac's Furrow), is also named after a mythological hero.

Romania

There are three valla in Romania, in south-central Dobruja, extending from the Danube to the Black Sea coast. While the relative chronology of the complex is widely accepted, the exact dating of each fortification is currently under dispute. Scholars place their erection at different dates in the Early Mediaeval period, in the second half of the first millennium. In what regards the builders, two theories have gained acceptance, with supporters split, to a large degree, along national lines. Thus, Bulgarian historiography considers the fortifications were built by the First Bulgarian Empire as a defence against the various nomad groups roaming the North-Pontic steppes. On the other hand, several Romanian historians have tried to attribute at least part of the walls to the Byzantine Empire under emperors John I Tzimisces and Basil II, which controlled the region in the second part of the 10th century and throughout the 11th.

The oldest and smallest vallum, the Small Earthen Dyke, is 61 km in length, extending from Cetatea Pătulului on the Danube to Constanţa on the sea coast. Entirely made of earth, it has no defensive constructions built on it, but has a moat on its southern side. This feature has been interpreted as indicating construction by a population living to the north of the earthwork, in order to protect itself from an enemy in the South.[2]

The second vallum, the Large Earthen Dyke, 54 km in length, overlaps the smaller one on some sections. It begins on the Danube, follows the Carasu Valley and ends at Palas, west of Constanţa. Its average height is 3.5 m, and it has moats on both sides. On it are built 63 fortifications: 35 larger (castra), and 28 smaller (castella). The average distance between fortifications is 1 km. The vallum shows signs of reconstruction.

The last vallum to be built, the Stone Dyke, is also made of earth, but has a stone wall on its crest. It is 59 km in length, extending from south of Axiopolis to the Black Sea coast, at a point 75 m south of the little earth wall. The agger is about 1.5 m in height, while the stone wall on top has an average height of 2 m. It has a moat on its northern side and 26 fortifications, the distance between them varying from 1 to 4 km.

The commune Valu lui Traian (formerly Hasancea) is named after the vallum.

In the Northern part of Dobrogea, on South bank of Danube there was a wall, probably built by Trajan. The wall was constructed between today Tulcea and ancient town of Halmyris (60 km) on the East. The wall was discovered by means of aerial photographs[3]

Moldova

The remnants in Moldova comprise earthen walls and palisades. There are two major fragments preserved in Moldova: Upper Trajan's Wall and Southern (or Lower) Trajan's Wall.

The Southern Trajan's Wall in Moldova is thought to be dated by the 3rd century, and built by Athanaric[4] and stretches from Romania: Buciumeni-Tiganesti-Tapu-Stoicani and in after that another 126 km from the village of Vadul in Cahul district by the Prut River stretches into Ukraine and ends at Lake Sasyk by Tatarbunar. The Coat of Arms of Cahul district of Bessarabia, Russian Empire, incorporated Trajan's Wall. Some academics like Dorel Bondoc and Costin Croitoru think that it was done by the Romans, because -to be done- it required plenty of knowledge and workforce that barbarians like Athanaric did not have. [5][6]

The Upper Trajan's Wall is thought to be constructed in the 4th century by Greuthungi Goths in order to defend the border against the Huns.[7] It stretches 120 km from Dniester River by Chiţcani in Teleneşti district to Prut River and extend until Tiganesti Sendreni in Romania.

Fragments of Trajan's Wall are also found by Leova.

Ukraine

The rampart known as Trajan's Wall in Podolia and stretches through the modern districts of Kamianets-Podilskyi, Nova Ushytsia(Uşiţa) and Khmelnytskyi. A part of the Moldavian Lower Trajan's Wall ends in Ukraine. See also Serpent's Wall.

The historian Alexandru V. Boldur regards the "Trajan's Wall" starting near Uşiţa on Dniester/Nistru river as the western limit of the territories of the 13th-century Bolokhoveni.

See also

- Upper Trajan's Wall

- Southern Trajan's Wall (in Bessarabia)

- Limes Moesiae

- Limes Romanus

- Limes Transalutanus

- Pietroasele

References

- Rădulescu Adrian, Bitoleanu Ion, Istoria românilor dintre Dunăre şi Mare: Dobrogea, Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică, Bucureşti, 1979

Notes

- Paolo Squatriti, "Moving Earth and Making Difference," in Florin Curta (ed.), Borders, Barriers and Ethnogenesis, Tournhout: Brepols, 2006, pp. 63-64

- "The protobulgarians on the northern and the western Black Sea coast", p.187, D.Dimitrov, 1987.

- Ioana Oltean, A lost archaeological landscape on the Lower Danube Roman limes: The contribution of second world war aerial photographs, in Archaeology from Historical Aerial and Satellite Archives, Springer New York, 2014, 147-164

- The Goths By Peter Heather page 100

- "Problema Valurilor": Roman Walls in Moldova (in Romanian)

- Costin Croitoru, Sudul Moldovei in cadrul sistemului defensiv roman. Contributii la cunosterea valurilor de pamant. Acta terrae septencastrensis, Editura Economica, Sibiu 2002, p.111.

- Peter Heather, The Goths, page 100

- A.V. Boldur, Istoria Basarabiei, Editura Victor Frunza, Bucuresti, pag.118