Course (navigation)

In navigation, the course of a watercraft or aircraft is the cardinal direction in which the craft is to be steered. The course is to be distinguished from the heading, which is the compass direction in which the craft's bow or nose is pointed.[1][2][3]

Course, track, route and heading

.svg.png)

1 - True North

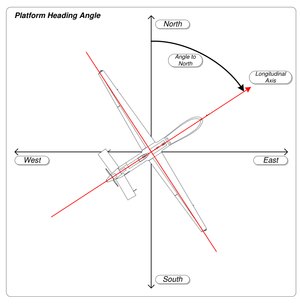

2 - Heading, the direction the vessel is "pointing towards"

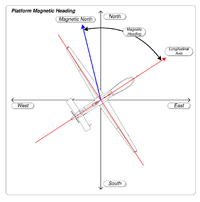

3 - Magnetic north, which differs from true north by the magnetic variation.

4 - Compass north, including a two-part error; the magnetic variation (6) and the ship's own magnetic field (5)

5 - Magnetic deviation, caused by vessel's magnetic field.

6 - Magnetic variation, caused by variations in earth's magnetic field.

7 - Compass heading or compass course, before correction for magnetic deviation or magnetic variation.

8 - Magnetic heading, the compass heading corrected for magnetic deviation but not magnetic variation; thus, the heading reliative to magnetic north.

9, 10 - Effects of crosswind and tidal current, causing the vessel's track to differ from its heading.

A, B - Vessel's track.

The path that a vessel follows over the ground is called a ground track, course made good or course over the ground.[1] For an aircraft it is simply its track.[3] The intended track is a route. For ships and aircraft, routes are typically straight-line segments between waypoints. A navigator determines the bearing (the compass direction from the craft's current position) of the next waypoint. Because water currents or wind can cause a craft to drift off course, a navigator sets a course to steer that compensates for drift. The helmsman or pilot points the craft on a heading that corresponds to the course to steer. If the predicted drift is correct, then the craft's track will correspond to the planned course to the next waypoint.[1][3] Course directions are specified in degrees from north, either true or magnetic. In aviation, north is usually expressed as 360°.[4] Navigators used ordinal directions, instead of compass degrees, e.g. "northeast" instead of 45° until the mid-20th century when the use of degrees became prevalent.[5]

See also

Notes

- Bartlett, Tim (February 25, 2008), Adlard Coles Book of Navigations, Adlard Coles, p. 176, ISBN 978-0713689396

- Husick, Charles B. (2009). Chapman Piloting, Seamanship and Small Boat Handling. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 927. ISBN 9781588167446.

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (2016-09-25). Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge: FAA-H-8083-25B. Ravenio Books.

- Michael Nolan (28 January 2010). Fundamentals of Air Traffic Control. Cengage Learning. p. 201. ISBN 1-4354-8272-7.

For example, a runway heading north would have a magnetic heading of 360°.

- Rousmaniere, John; Smith, Mark (1999). The Annapolis Book of Seamanship: Third Edition: Completely Revised, Expanded and Updated. Simon and Schuster. p. 234. ISBN 9780684854205.