Toppenish, Washington

Toppenish (/ˈtɒppənɪʃ/) is a city in Yakima County, Washington, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 8,949. It is located within the Yakama Indian Reservation, established in 1855.

Toppenish, Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

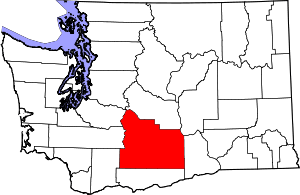

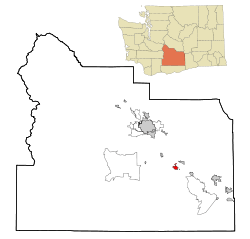

Location of Toppenish in Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°22′44″N 120°18′43″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Yakima |

| Founded | 1884 |

| Incorporated | April 29, 1907 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Body | City council |

| • Mayor | Mark Oaks |

| • City manager | Lance Hoyt |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.13 sq mi (5.53 km2) |

| • Land | 2.13 sq mi (5.53 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 758 ft (231 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 8,949 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 8,809 |

| • Density | 4,126.00/sq mi (1,592.75/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98948 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-71960 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512732[4] |

| Website | cityoftoppenish.us |

Toppenish calls itself the Town of Murals, as it has more than 75 murals adorning its buildings. The first, "Clearing the Land", was painted in 1989, and the city hosts horse-drawn tours and annual art events. All historically accurately depict scenes of the region from 1840 to 1940.[5][6][7][8]

History

All territory set aside for the Yakama Reservation by the Treaty of 1855 was held communally in the name of the tribe. None of the land was individually owned. The treaty of 1855, between the United States government, representatives from thirteen other bands, tribes, and Chief Kamiakin, resulted in the Yakama Nation relinquishing 16,920 square miles (43,800 km2) of their homeland. Prior to their ceding the land, only Native Americans had lived in the area.

For a time they were not much disturbed, but the railroad was constructed into the area in 1883. More white settlers migrated into the region, looking for farming land, and joined the ranchers in older settlements bordering the Columbia River.

The General Allotment Act of 1887 (known as the Dawes Act) was part of federal legislation designed to force assimilation to European-American ways by Native Americans. Specifically, it was designed to break up the communal tribal land of Native American reservations and allot portions to individual households of tribal members, in order to encourage subsistence farming in the European-American style and familiarity with western conceptions of property. Lands declared excess by the government to this allotment were available for sale to anyone, and European Americans had been demanding more land in the West for years. Under varying conditions, Native American landowners were to be allowed to sell their plots.

Josephine Bowser Lillie was among Native Americans granted an 80-acre (320,000 m2) allotment of land within the Yakama Reservation. Of mixed Native American/European ancestry and Yakama identification, she is known as "The Mother of Toppenish." She platted the north 40 acres (160,000 m2) of her land. These tracts became the first deeded land to be sold on the Yakama Nation Reservation.

Tẋápniš in the Sahaptin language of the Yakama. This is the likely source of the name Toppenish. The word means ‘protruded, stuck out’ and recalls a landslide that occurred on the ridge south of White Swan, Washington.[9] According to William Bright, the name "Toppenish" comes from the Sahaptin word /txápniš/, referring to a landslide, from /txá-/, "accidentally", /-pni-/, "to launch, to take forth and out", and /-ša/, "continuative present tense".[10] Another theory suggests the name may come from Thap-pahn-ish meaning "People of the trail which comes from the foot of the hills" or from Qapuishlema which means "People from the foot of the hills." Or it was derived from the name of a Lower Yakama band along the Toppenish Creek, which was called Thápnĭś-ħlama.

The city lies inside the boundaries of the Yakama Nation's Reservation. Toppenish was officially incorporated on April 29, 1907, and founded by Johnny Barnes.

Early development

A driving figure in Toppenish's early development was William Leslie Shearer (October 31, 1862 – June 5, 1922). Since Toppenish had no church in 1897 Shearer obtained permission from the Northern Pacific Railroad Company and offered the freight room for religious services. Following this, he helped organize the first Methodist Church and, as trustee, was instrumental in the construction of a building that would house the church and also serve as school classrooms until a separate schoolhouse could be built. The building was completed in time for the 1898-1899 school term.

After leaving the employment of the railroad, Shearer, with Frank J. Lemon as his partner, opened Toppenish's first drugstore in 1905. About a year later, Shearer sold out, turning his attention to the newly organized Yakima Produce and Trading company, with George Plank, A.W. McDonald and M. McDonald as partners. The company bought some acreage and leased more sagebrush land to develop the 1700-acre ranch near Satus Station. Shearer had a system of irrigation ditches constructed leading from Satus Creek to the acreage.

Geography

Toppenish is located at 46°22′44″N 120°18′43″W (46.378880, -120.311823).[11]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.09 square miles (5.41 km2), all of it land.[12]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 1,598 | — | |

| 1920 | 3,120 | 95.2% | |

| 1930 | 2,774 | −11.1% | |

| 1940 | 3,683 | 32.8% | |

| 1950 | 5,265 | 43.0% | |

| 1960 | 5,667 | 7.6% | |

| 1970 | 5,744 | 1.4% | |

| 1980 | 6,517 | 13.5% | |

| 1990 | 7,419 | 13.8% | |

| 2000 | 8,946 | 20.6% | |

| 2010 | 8,949 | 0.0% | |

| Est. 2019 | 8,809 | [3] | −1.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] 2018 Estimate[14] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 8,949 people, 2,237 households, and 1,900 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,281.8 inhabitants per square mile (1,653.2/km2). There were 2,334 housing units at an average density of 1,116.7 per square mile (431.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 33.8% White, 0.7% African American, 8.0% Native American, 0.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 52.6% from other races, and 4.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 82.6% of the population.

There were 2,237 households of which 62.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.8% were married couples living together, 19.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 10.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 15.1% were non-families. 11.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.96 and the average family size was 4.22.

The median age in the city was 24.3 years. 37.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 13.7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25% were from 25 to 44; 17.2% were from 45 to 64; and 6.7% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 51.3% male and 48.7% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 8,946 people, 2,275 households, and 1,874 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,762.7 people per square mile (1,837.3/km²). There were 2,440 housing units at an average density of 1,299.0 per square mile (501.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 31.48% White, 0.56% Black or African American, 7.90% Native American, 0.37% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 55.95% from other races, and 3.72% from two or more races. 75.72% of the population identified as Hispanic or Latino. There were 2,275 households out of which 52.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.1% were married couples living together, 16.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 17.6% were non-families. 14.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.88 and the average family size was 4.26.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 38.8% under the age of 18, 11.7% from 18 to 24, 27.5% from 25 to 44, 14.2% from 45 to 64, and 7.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 25 years. For every 100 females, there were 106.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 103.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,950, and the median income for a family was $28,228. Males had a median income of $22,264 versus $19,704 for females. The per capita income for the city was $9,101. About 29.2% of families and 32.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 38.1% of those under age 18 and 14.8% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Public schools are operated by the Toppenish School District, whose offices are located here. The Yakima Nation also operates the Yakama Nation Tribal School.

Notable people

A.B. Quintanilla was born in Toppenish, Washington on December 13, 1963. He is the older brother of superstar Selena Quintanilla Perez. He is known for his Tejano group Kumbia Kings.

Serial killer Westley Allan Dodd was born in Toppenish.[15]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "MURALS. Mural Tour Informatiom". toppenish-chamber. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- "Toppenish Chamber of Commerce". www.scenicwa.com. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- "Toppenish murals". Yakima Herald-Republic. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- "The Toppenish Murals: Where the West Still Lives". www.amazon.com. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- Beavert, Virginia and Hargus, Sharon. Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit Yakama = Yakima Sahaptin dictionary. Toppenish, Washington : Heritage University ; Seattle : in association with the University of Washington Press, 2009; p. 237. OCLC 268797329

- Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 508. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Egan, Timothy (29 December 1992). "Illusions Are Also Left Dead As Child-Killer Awaits Noose". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toppenish, Washington. |