Tombs at Xanthos

Xanthos, also called Xanthus, was a chief city state of the Lycians, an indigenous people of southwestern Anatolia (present-day Turkey).[1] Many of the tombs at Xanthos are pillar tombs, formed of a stone burial chamber on top of a large stone pillar. The body would be placed in the top of the stone structure, elevating it above the landscape. The tombs are for men who ruled in a Lycian dynasty from the mid-6th century to the mid-4th century BCE and help to show the continuity of their power in the region.[2] Not only do the tombs serve as a form of monumentalization to preserve the memory of the rulers, but they also reveal the adoption of Greek style of decoration.

.jpg)

Xanthos was chief city state governed by a king, who was under an Achaemenid Empire governor. The continuity of the dynastic rule in Xanthos was shown through a tradition of building pillar tombs.[1] When these tombs were made, predominant Late Classical Greek ideas of art pervaded Lycian imagery.[1] The tombs moved away from the local tradition and started to display the facades of pillared Greek Temples following the resurgence of Greek influence in the erea, from the 2nd quarter of the 4th century BCE (375-350 BCE).[3]

Several tombs were excavated by Sir Charles Fellows, an Englishman who excavated in the Levant and Asia Minor,[4] and were transported to the British Museum in 1848 C.E.[5]

Monumental pillar tombs

Lion Pillar

The “Lion Pillar,” named because of the large lion in high relief, was located east of the Acropolis of Xanthos and stands around three meters high (around ten feet). The stone chest is made of white limestone, carved to fit the body. It has been postulated that this tomb was created between the early sixth century B.C.E. and the mid-sixth century B.C.E. Contrast is created between the high relief sculpture on the ends and the low relief sculpture in the center of the chest.[5] The details of the friezes indicate that the craftsmen were Greek, not Lycian. The stylistic features that distinguish Greek craftsmanship are revealed through the depictions of the human form on the West side of the chest. A lion is held by a man, whose body simply delineated: nude and with few defining curves. His archaic smile and hair falling in locks also indicates a strong Archaic Greek style.[5][6]

On the south side of the front of the chest is the figure of a recumbent lion, carved in high relief. The lion is facing left, its body contained within the end of the block. The small head of a bull, who has been pinned by the lion, rests between its paws. Below the bull was a tablet, the inscription on which has faded. The North side of the monument features more imagery of lions, in a position of caring for young, as a lion interacts with her cubs. The carving technique used in this relief is similar to the one used on the South side of the frieze, with the details and outline of the form delineated by use of line. While the lion on the South side has weight and mass, the lion on the east side has a thinner form.[5]

On the east side of the monument, the composition is broken up into registers, the lower half remaining undecorated and the upper half most likely containing a low relief frieze. However, the complete length of the top frieze is unknown because part of it has broken off, limiting the information that can be gained from the images. On the left part of the east side of the monument, militaristic scenes in low relief depict soldiers with gear for war, including a shield, a Corinthian helmet, and a weapon. On the right side of the frieze is a horseman, dressed in a short cloak and a helmet, accompanied by an attendant wearing a chiton, a Greek-style tunic, carrying a spear.[5]

Harpy Tomb

.jpg)

.jpg)

The "Harpy Tomb" was most likely made around 480-470 B.C.E. The decorations are made in the Greek Archaic Style and the tomb was located on the Acropolis of Xanthos.

The interpretation of the iconography of the “Harpy Tomb” have developed over time. Initially, it was believed that the winged females on the frieze referenced a myth about violence done to the Lycian royal family. Then, it was postulated that because the tomb was fabricated by Greek artisans and workmen, the imagery referenced a scene of the underworld, using iconography to underscore the funerary use of the structure. Tombs on mainland Greece produced at this time did not include the figures of gods, as are depicted, so a third theory was developed. The third theory is that the multiple generations of figures depicted around the image are an indication of hero worship centered around the individuals who could have been buried within the tomb.[7]

Inscribed Pillar

.jpg)

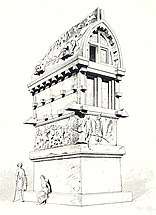

The Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos, also known as the "Xanthian Obelisk," was made around 400 B.C.E.[8] Like the other pillar tombs at Xanthos, the inscribed pillar supported a raised daise with a chamber tomb, decorated on the outside with friezes. Additionally, a statue of the occupant, a king in the Xanthian Dynasty, was positioned on top.[9] The chamber tomb was surrounded by friezes depicting scenes from the life of the owner, including hunting and battle scenes.[9] Seismic activity in antiquity likely caused the chamber tomb of fall off.[10]

The inscriptions on the side of the pillar provide room for scholarly speculation as to the creators of the monument. Greek and two different types of Lycian inscriptions mark the sides of the pillar, with each inscription addressing different topics.[9] The Greek inscription is a dedication of the monument, likely to twelve Greek gods, and is the oldest Greek inscription known in Lycia.[9] The inscriptions in Lycian B has not yet been fully deciphered, but the inscriptions in Lycian A, the last to be inscribed on the pillar, has been translated.[9] The creator of the Inscribed Pillar is unknown, because several of the letters forming the individual's name in the Lycian inscription is missing.[8]

Other monumental burials

Nereid Monument

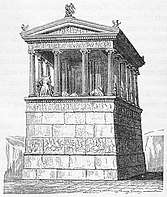

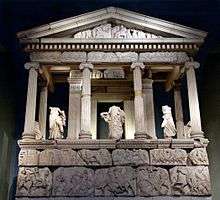

The “Nereid Monument” is another monumental tomb, named for the three figures of women between the columns on the front of the building. The tomb was built in the Ionic order (as the columns have volutes at tops and bases underneath them) and its form resembles an Ionic temple.[11] The temple was built around 380 B.C.E. by Greek sculptors and architects.[12] This funerary architecture parallels the religious architecture well-developed in Greece during the late Classical period. Just as the Nereid monument was influenced by Greek art and architecture, so too did it influence regional architecture after it. In fact, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was directly influenced by the Nereid Monument.[13]

The building and the podium it rests upon are covered in relief sculpture. The women who lend their title to the monument have been identified as Nereids, as they could have appeared to the Greeks, or as water nymphs who were part of a local Lycian cult. The “hybrid iconography” present in the monument allows for multiple interpretations.[11] The expression of power is a pervasive theme in the monument, despite being a tomb. The grand size and position within a dynastic tradition of pillar tombs helps to express the sources of power of the ruler, King Erbinna of the Xanthian Dynasty, buried within. Throughout the monument are many references to Erbinna's power, as the friezes depict both scenes of political development (court scene) as well as scenes of battle. On the podium, the iconography is mixed, utilizing Greek iconography on the bottom two friezes and the 8th to 7th century B.C.E. Assyrian iconography of power on the top two reliefs.[11] Each set of friezes, in the podium, architrave, and interior, each show scenes of political life and recreation, as well as civic and religious duties.[12]

Additional tombs

Other tombs were present at Xanthos. They include the "Pillar of the Wrestlers," the "Theatre Pillar," the "Acropolis Pillar," and the "Tomb of Payava."

Stylistic Influences

.jpg)

The tombs at Xanthos derived their form and decoration from multiple international sources.[6] The form of the pillar tomb was a distinctively Lycian architectural type.[6] Lycian, Greek, and Persian styles and iconographies combined in the relief sculpture of the tombs at Xanthos.[6] Lycian imagery included predominant Late Classical Greek ideas of art such as a connection with the viewer, individualist expressions, centralized power and wealth, and new definitions of divinity.[1] These themes can be seen through an examination of the relief sculpture of the monuments, specifically relating to the dynastic continuity between generations of Lycian rulers. Depictions of powerful individuals using styles from surrounding regions, even after the individuals's death, indicates cultural awareness and control.

The tombs at Xanthos feature distinctive styles of relief sculpture that attest to the Greek influence in Anatolia during the Late Classical period. The use of Greek style in regions east of Greece are known as "East Greek" style.[6] Some Greek stylistic influence was very direct, with some relief sculpture in Xanthos made by Greek artisans. Examples include the reliefs sculpture on the Nereid Monument and depictions of hunters and lions in the Greek Archaic style on the Lion Tomb.[6] The Archaic style manifested itself in gridlike, proportional depictions of forms, not characterized by large amounts of movement.[14] The Nereid Monument exemplifies the combination of Lycian, Greek, and Persian artistic styles because it combines Greek architectural forms and styles of motifs with Near Eastern iconography in the relief sculpture atop the Iconic-style pediment.[6]

- Phoenicia

The shape of the Lycian ogival tomb was adopted for the "Lycian" sarcophagus of Sidon, a tomb for a king of Phoenicia (modern Lebanon), built by Ionian artists circa 430-420 BCE.[15][16][17]

Indian architectural parallels

The similarity of the tomb of Payava, and more generally the Lycian barrel-vaulted tombs, with the Indian Chaitya architectural design (starting from circa 250 BCE with the Lomas Rishi caves in the Barabar caves group) has also been remarked on. James Fergusson, in his " Illustrated Handbook of Architecture", while describing the very progressive evolution from wooden architecture to stone architecture in various ancient civilizations, has commented that "In India, the form and construction of the older Buddhist temples resemble so singularly these examples in Lycia".[18]

The Lycian tombs, dated to the 4th century BCE, are either free-standing or rock-cut barrel-vaulted sarcophagi, placed on a high base, with architectural features carved in stone to imitate wooden structures. There are numerous rock-cut equivalents to the free-standing structures. Both Greek and Persian influences can be seen in the reliefs sculpted on the sarcophagus.[19] The structural similarities, down to many architectural details, with the Chaitya-type Indian Buddhist temple designs, such as the "same pointed form of roof, with a ridge", are further developed in The cave temples of India.[20] Fergusson went on to suggest an "Indian connection", and some form of cultural transfer across the Achaemenid Empire.[21]

The known Indian designs for the Chaityas only start from circa 250 BCE with the Lomas Rishi caves in the Barabar caves group, and therefore postdate the Xanthos barrel-vaulted tombs by at least one century.[22] The Achaemenids occupied the northwestern parts of India from circa 515 BCE to 323 BCE following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, before they were replaced with the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great and subsequent Hellenistic influence in the region.

Art historian David Napier has also proposed a reverse relationship, claiming that the Payava tomb was a descendant of an ancient South Asian style, and that Payava may actually have been a Graeco-Indian named "Pallava".[23]

References

- Neer, Richard (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology. New York, New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-500-28877-1.

- Keen, Anthony (1992). "The Dynastic Tombs of Xanthos: Who Was Buried Where?". Anatolian Studies. 42: 53–63. doi:10.2307/3642950. JSTOR 3642950.

- Borza, Eugene N. (1992). In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon. Princeton University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0691008806.

- "Sir Charles Fellows (Biographical Details)". The British Museum.

- "burial-chest". The British Museum.

- Metzger, Henri; Opper, Thorsten. "Xanthos". Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "tomb". The British Museum. 26 October 2017.

- Childs, William (1979). "The Authorship of the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos". Anatolian Studies. 29: 97–102. doi:10.2307/3642733. JSTOR 3642733.

- Gygax, Marc Domingo (2005). "'He Who of All Mankind Set up the Most Numerous Trophies to Zeus:' The Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos Reconsidered". Anatolian Studies. 55: 89–96. doi:10.1017/s0066154600000661. JSTOR 20065536.

- Fellows, Charles (1840). An account of discovery in Lycia, being a journal kept during second exclusion in Asia Minor. London: J. Murray. p. 170.

- Neer, Richard (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology. New York, New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-500-28877-1.

- "The Nereid Monument at Xanthos". Classical Art Research Centre and The Beazley Archive. 26 October 2012.

- "Xanthos-Leotoon". UNESCO. 25 October 2017.

- Neer, Richard (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 151.

- Rose, Charles Brian (2014). The Archaeology of Greek and Roman Troy. Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 9780521762076.

- Palagia, Olga (2017). Regional Schools in Hellenistic Sculpture. Oxbow Books. p. 285. ISBN 9781785705489.

- Freely, John; Glyn, Anthony (2000). The Companion Guide to Istanbul and Around the Marmara. Companion Guides. p. 71. ISBN 9781900639316.

- The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture Being a Concise and Popular Account of the Different Styles of Architecture Prevailing in All Ages and All Countries by James Fergusson. J. Murray. 1859. p. 212.

- M. Caygill, The British Museum A-Z compani (London, The British Museum Press, 1999) E. Slatter, Xanthus: travels and discovery (London, Rubicon Press, 1994) A.H. Smith, A catalogue of sculpture in -1, vol. 2 (London, British Museum, 1900)

- Fergusson, James; Burgess, James (1880). The cave temples of India. London : Allen. p. 120.

- Fergusson, James (1849). An historical inquiry into the true principles of beauty in art, more especially with reference to architecture. London, Longmans, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 316–320.

- Ching, Francis D. K.; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (2010). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 164. ISBN 9781118007396.

- According to David Napier, author of Masks, Transformation, and Paradox, "In the British Museum we find a Lycian building, the roof of which is clearly the descendant of an ancient South Asian style.", "For this is the so-called "Tomb of Payava" a Graeco-Indian Pallava if ever there was one." in "Masks and metaphysics in the ancient world: an anthropological view" in Malik, Subhash Chandra; Arts, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the (2001). Mind, Man, and Mask. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. p. 10. ISBN 9788173051920.