Ferdinand Tönnies

Ferdinand Tönnies (German: [ˈtœniːs]; Oldwenswort, 26 July 1855 – Kiel, 9 April 1936) was a German sociologist, economist and philosopher. He was a major contributor to sociological theory and field studies, best known for his distinction between two types of social groups, Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft (Community and Society). He co-founded the German Society for Sociology alongside Max Weber and Georg Simmel and many other founders. He was president of the society from 1909 to 1934,[1] after which he was ousted for having criticized the Nazis. Tönnies was considered the first German sociologist proper,[2] published over 900 works and contributed to many areas of sociology and philosophy.

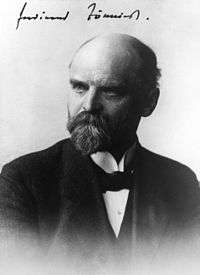

Ferdinand Tönnies | |

|---|---|

Tönnies, c.1915 | |

| Born | 26 July 1855 |

| Died | 9 April 1936 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | Germany |

| Alma mater | University of Jena University of Bonn University of Leipzig University of Berlin University of Tübingen |

| Known for | Sociological Theory; distinction between two types of social groups, Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Sociology |

| Institutions | University of Kiel |

Life

Ferdinand Tönnies was born 26 July 1855 on the Haubuarg 'De Reap", Oldenswort on the Eiderstedt Peninsula into a wealthy farmer's family in North Frisia, Schleswig, then under Danish rule. He was the third child of church chief and farmer August Ferdinand Tönnies (1822–1883) and his wife Ida Frederica (born Mau, 1826–1915) who came from a theological family from East Holstein. The two had seven children, four sons and three daughters. On the day he was born, Ferdinand Tönnies received the baptismal name of Ferdinand Julius.

Tönnies was the only sociologist of his generation who came from the countryside. At the age of 16, he graduated from high school in Husum and later studied at the universities of Jena, Bonn, Leipzig, Berlin, and Tübingen. At age 22, he received a doctorate in philology at the University of Tübingen in 1877 (with a Latin thesis on the ancient Siwa Oasis).[3] At the age of 25, he habilitated with a thesis on the life and work of Thomas Hobbes at the Christian Albrechts University in Kiel. He taught at the University of Kiel from 1909 to 1933 and eventually became a private lecturer. He held this post at the University of Kiel for only three years. Because he sympathized with the Hamburg dockers' strike of 1896,[4] the conservative Prussian government considered him to be a social democrat, and Tönnies would not be called to a professorial chair until 1913. He returned to Kiel as a professor emeritus in 1921 where he took on a teaching position in sociology and taught until 1933 when he was ousted by the Nazis, due to earlier publications in which he had criticized them.[5] Remaining in Kiel, he died three years later in 1936.

Many of his writings on sociological theories—including Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887)—furthered pure sociology. He coined the metaphysical term Voluntarism. Tönnies also contributed to the study of social change, particularly on public opinion,[6] customs and technology, crime, and suicide.[7] He also had a vivid interest in methodology, especially statistics, and sociological research, inventing his own technique of statistical association.[8]

Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

Tönnies distinguished between two types of social groupings. Gemeinschaft—often translated as community (or left untranslated)—refers to groupings based on feelings of togetherness and on mutual bonds, which are felt as a goal to be kept up, their members being means for this goal. Gesellschaft—often translated as society—on the other hand, refers to groups that are sustained by it being instrumental for their members' individual aims and goals.

Gemeinschaft may be exemplified historically by a family or a neighborhood in a pre-modern (rural) society; Gesellschaft by a joint-stock company or a state in a modern society, i.e. the society when Tönnies lived. Gesellschaft relationships arose in an urban and capitalist setting, characterized by individualism and impersonal monetary connections between people. Social ties were often instrumental and superficial, with self-interest and exploitation increasingly the norm. Examples are corporations, states, or voluntary associations. In his book Einteilung der Soziologie (Classification of Sociology) he distinguished between three disciplines of sociology the latter being Pure or Theoretical (reine, theoretische) Sociology, Applied (angewandte) Sociology, and Empirical (emprische) Sociology.

His distinction between social groupings is based on the assumption that there are only two basic forms of an actor's will, to approve of other men. For Tönnies, such an approval is by no means self-evident; he is quite influenced by Thomas Hobbes.[2] Following his "essential will" ("Wesenwille"), an actor will see himself as a means to serve the goals of social grouping; very often it is an underlying, subconscious force. Groupings formed around an essential will are called a Gemeinschaft. The other will is the "arbitrary will" ("Kürwille"): An actor sees a social grouping as a means to further his individual goals; so it is purposive and future-oriented. Groupings around the latter are called Gesellschaft. Whereas the membership in a Gemeinschaft is self-fulfilling, a Gesellschaft is instrumental for its members. In pure sociology—theoretically—these two normal types of will are to be strictly separated; in applied sociology—empirically—they are always mixed.

Criticisms

Tönnies' distinction between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft, like others between tradition and modernity, has been criticized for over-generalizing differences between societies, and implying that all societies were following a similar evolutionary path, an argument which he never proclaimed.[9] The equilibrium in Gemeinschaft is achieved through means of social control, such as morals, conformism, and exclusion, while Gesellschaft keeps its equilibrium through police, laws, tribunals and prisons. Amish, Hassidic communities are examples of Gemeinschaft, while states are types of Gesellschaft. Rules in Gemeinschaft are implicit, while Gesellschaft has explicit rules (written laws).

Published works (selection)

- 1887: Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, Leipzig: Fues's Verlag, 2nd ed. 1912, 8th edition, Leipzig: Buske, 1935 (reprint 2005, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft; latest edition: Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. 1880–1935., hrsg. v. Bettina Clausen und Dieter Haselbach, De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston 2019 = Ferdinand Tönnies Gesamtausgabe, Band 2); his basic and never essentially changed study of social man; translated in 1957 as "Community and Society", ISBN 0-88738-750-0

- 1896: Hobbes. Leben und Lehre, Stuttgart: Frommann, 1896, 3rd edn 1925; a philosophical study that reveals his indebtedness to Hobbes, many of whose writings he has edited

- 1897: Der Nietzsche-Kultus, Leipzig: Reisland

- 1905: "The Present Problems of Social Structure", in: American Journal of Sociology, 10(5), p. 569–588 (newly edited, with annotations, in: Ferdinand Tönnies Gesamtausgabe, tom. 7, Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter 2009, p. 269–285)

- 1906: Philosophische Terminologie in psychologischer Ansicht, Leipzig: Thomas

- 1907: Die Entwicklung der sozialen Frage, Leipzig: Göschen

- 1909: Die Sitte, Frankfurt on Main: Rütten & Loening

- 1915: Warlike England as seen by herself, New York: Dillingham

- 1917: Der englische Staat und der deutsche Staat, Berlin: Curius; pioneering political sociology

- 1921: Marx. Leben und Lehre, Jena: Lichtenstein

- 1922: Kritik der öffentlichen Meinung, Berlin: Springer; 2nd ed. 2003, Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter (Ferdinand Tönnies Gesamtausgabe, tom. 14); translated as On Public Opinion. Applied sociology revealing Tönnies' thorough scholarship and his commitment as an analyst and critic of modern public opinion

- 1924, 1926, and 1929: Soziologische Studien und Kritiken, 3 vols, Jena: Fischer, a collection in three volumes of those papers he considered most relevant

- 1925, Tönnies, F. Einteinlung der Soziologie. Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Staatswissenschaft. English translation: Classification of Sociology. Journal of the Complete Political Science/ Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 79(1), 1–15. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40744384

- 1926: Fortschritt und soziale Entwicklung, Karlsruhe: Braun

- 1927: Der Selbstmord in Schleswig-Holstein, Breslau: Hirt

- 1931: Einführung in die Soziologie, Stuttgart: Enke. His fully elaborated introduction into sociology as a social science

- 1935: Geist der Neuzeit, Leipzig: Buske; 2nd ed. 1998 (in: Ferdinand Tönnies Gesamtausgabe, tom. 22); a study in applied sociology, analysing the transformation from European Middle Ages to modern times

- 1971: On Sociology: Pure, Applied, and Empirical. Selected writings edited and with an introd. by Werner J. Cahnman and Rudolf Heberle. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-80607-3

- 1974: On Social Ideas and Ideologies. Edited, Translated, and Annotated by E. G. Jacoby, Harper & Row

- 1998–: Tönnies' Complete Works (Ferdinand Tönnies Gesamtausgabe), 24 vols., critically edited by Lars Clausen, Alexander Deichsel, Cornelius Bickel, Rolf Fechner (until 2006), Carsten Schlüter-Knauer, and Uwe Carstens (2006– ), Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter (1998– )

- Materialien der Ferdinand-Tönnies-Arbeitsstelle am Institut für Technik- und Wissenschaftsforschung der Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt, edited by Arno Bammé:

- 2008: Soziologische Schriften 1891–1905, ed. Rolf Fechner, Munich/Vienna: Profil

- 2009: Schriften und Rezensionen zur Anthropologie, ed. Rolf Fechner, Munich/Vienna: Profil

- 2009: Schriften zu Friedrich von Schiller, ed. Rolf Fechner, Munich/Vienna: Profil

- 2010: Schriften und Rezensionen zur Religion, ed. Rolf Fechner, Profil, Munich/Vienna: Profil

- 2010: Geist der Neuzeit, ed. Rolf Fechner, Profil-Verlag, Munich/Vienna: Profil

- 2010: Schriften zur Staatswissenschaft, ed. Rolf Fechner, Profil, Munich/Vienna: Profil

- 2011: Schriften zum Hamburger Hafenarbeiterstreik, ed. Rolf Fechner, Munich/Vienna: Profl

See also

- Ferdinand-Tönnies-Gesellschaft (Ferdinand Tönnies Society)

- Voluntarism (metaphysics)

- Hamburg dockers strike 1896/97 [German]

Notes

- "Obituary: Ferdinand Tonnies 1855–1936". American Journal of Sociology. 42 (1): 100–101. 1936. doi:10.1086/217334. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2768866.

- See Louis Wirth, The Sociology of Ferdinand Tonnies, in American Journal of Sociology Vol. 32, No. 3 (Nov. 1926), pp. 412–422. JSTOR 2765542See R. Heberle, The Sociology of Ferdinand Tönnies, in American Sociological Review, (1937) 2(1), pp. 9–25. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2084562

- De Jove Ammone questionum specimen, Phil. Diss., Tübingen 1877

- Ferdinand Tönnies: Hafenarbeiter und Seeleute in Hamburg vor dem Strike 1896/97, in: Archiv für soziale Gesetzgebung und Statistik, 1897, vol. 10/2, p. 173-238

- See Uwe Carsten, Ferdinand Tönnies: Friese und Weltbürger, Norderstedt 2005, p. 287–299.

- Kritik der öffentlichen Meinung, [1922], in: Ferdinand Tönnies Gesamtausgabe, tom. 14, ed. Alexander Deichsel/Rolf Fechner/Rainer Waßner, de Gruyter, Berlin/New York 2002

- Cf. Der Selbstmord von Maennern in Preussen, [Mens en Maatschappij, 1933], in: Ferdinand Tönnies Gesamtausgabe, tom. 22, ed. Lars Clausen, de Gruyter, Berlin/New York 1998, p. 357-380.

- Lars Clausen: Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936), in: Christiana Albertina, No. 63, Kiel 2006, p. 663-69

- Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, Leipzig 1887, §§ 1–40

References

- Adair-Toteff, C., Ferdinand Tönnies: Utopian Visionar, in: Sociological Theory, vol. 13, 1996, p. 58–65

- Bickel, Cornelius: Ferdinand Tönnies: Soziologie als skeptische Aufklärung zwischen Historismus und Rationalismus, Opladen: Westdt. Verlag, 1991.

- Bond, Niall, "Ferdinand Tönnies's Romanticism," The European Legacy, 16.4 (2011), 487–504.

- Cahnman, Werner J. (ed.), Ferdinand Tönnies: A New Evaluation, Leiden, Brill, 1973.

- Cahnman, Werner J., Weber and Toennies: Comparative Sociology in Historical Perspective. New Brunswick: Transaction, 1995.

- Cahnman, Werner J./Heberle, Rudolf: Ferdinand Toennies on Sociology: Pure, Applied and Empirical, 1971.

- Carstens, Uwe: Ferdinand Tönnies: Friese und Weltbürger, Norderstedt: Books on Demand 2005, ISBN 3-8334-2966-6 [Biography, German]

- Clausen, Lars: The European Revival of Tönnies, in: Cornelius Bickel/Lars Clausen, Tönnies in Toronto, C.A.U.S.A. 26 (Christian-Albrechts-Universität • Soziologische Arbeitsberichte), Kiel 1998, p. 1–11

- Clausen, Lars: Tönnies, Ferdinand, in: Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie, tom. X, Munich: K. G. Saur ²2008, p. 60–62 [German]

- Clausen, Lars/Schlüter, Carsten (eds.): Hundert Jahre "Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft", Opladen: Leske + Budrich 1991 [German]

- Deflem, Mathieu, "Ferdinand Tönnies on Crime and Society: An Unexplored Contribution to Criminological Sociology." History of the Human Sciences 12(3):87–116, 1999

- Deflem, Mathieu, "Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936)." In the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy Online, edited by Edward Craig. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Fechner, Rolf: Ferdinand Tönnies – Werkverzeichnis, Berlin/New York (Walter de Gruyter) 1992, ISBN 3-11-013519-1 [Bibliography, German]

- Fechner, Rolf: Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936), in: Handbuch der Politischen Philosophie und Sozialphilosophie, Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-017408-3, p. 1347–1348

- Ionin, Leonid: "Ferdinand Tönnies' Sociological Conception", translated by H. Campbell Creighton, in: Igor Kon (ed.), A History of Classical Sociology (pp. 173–188). Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1989.

- Jacoby, Eduard Georg: Die moderne Gesellschaft im sozialwissenschaftlichen Denken von Ferdinand Tönnies, Stuttgart: Enke 1971 [German]

- Merz-Benz, Peter-Ulrich: Tiefsinn und Scharfsinn: Ferdinand Tönnies' begriffliche Konstitution der Sozialwelt, Frankfurt on Main 1995 (same year: Amalfi Prize) [German]

- Podoksik, Efraim: 'Overcoming the Conservative Disposition: Oakeshott vs. Tönnies. Political Studies 56(4):857–880, 2008.

External links

- Ferdinand Tönnies: Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft – Abhandlung des Communismus und des Sozialismus als empirischer Kulturforment at the Internet Archive

- Ferdinand Tönnies: Hobbes Leben und Lehre at the Internet Archive

- Ferdinand Tönnies: Philosophische Terminologie in psychologisch-soziologischer Ansicht at the Internet Archive

- Ferdinand Tönnies: Englische Weltpolitik in englischer Beleuchtung at the Internet Archive

- Ferdinand-Tönnies-Gesellschaft

- Newspaper clippings about Ferdinand Tönnies in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW