Tipu's Tiger

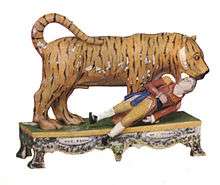

Tipu's Tiger or Tippu's Tiger is an eighteenth-century automaton or mechanical toy created for Tipu Sultan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in India. The carved and painted wood casing represents a tiger savaging a near life-size European man. Mechanisms inside the tiger and man's bodies make one hand of the man move, emit a wailing sound from his mouth and grunts from the tiger. In addition a flap on the side of the tiger folds down to reveal the keyboard of a small pipe organ with 18 notes.

The tiger was created for Tipu and makes use of his personal emblem of the tiger and expresses his hatred of his enemy, the British of the East India Company. The tiger was discovered in his summer palace after East India Company troops stormed Tipu's capital in 1799. The Governor General, Lord Mornington sent the tiger to Britain initially intending it to be an exhibit in the Tower of London. First exhibited to the London public in 1808 in East India House, then the offices of the East India Company in London, it was later transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in 1880 (accession number 2545(IS)).[1] It now forms part of the permanent exhibit on the "Imperial courts of South India".[2] From the moment it arrived in London to the present day, Tipu's Tiger has been a popular attraction to the public.

Background

Tipu's Tiger was originally made for Tipu Sultan (also referred to as Tippoo Saib, Tippoo Sultan and other epithets in nineteenth-century literature) in the Kingdom of Mysore (today in the Indian state of Karnataka) around 1795.[3] Tipu Sultan used the tiger systematically as his emblem, employing tiger motifs on his weapons, on the uniforms of his soldiers, and on the decoration of his palaces.[4] His throne rested upon a probably similar life-size wooden tiger, covered in gold; like other valuable treasures it was broken up for the highly organised prize fund shared out between the British army.[5][6]

Tipu had inherited power from his father Hyder Ali, a Muslim soldier who had risen to become dalwai or commander-in-chief under the ruling Hindu Wodeyar dynasty, but from 1760 was in effect the ruler of the kingdom. Hyder, after initially trying to ally with the British against the Marathas, had later become their firm enemy, as they represented the most effective obstacle to his expansion of his kingdom, and Tipu grew up with violently anti-British feelings.[7]

The tiger formed part of a specific group of large caricature images commissioned by Tipu showing European, often specifically British, figures being attacked by tigers or elephants, or being executed, tortured and humiliated and attacked in other ways. Many of these were painted by Tipu's orders on the external walls of houses in the main streets of Tipu's capital, Seringapatam.[8] Tipu was in "close co-operation" with the French, who were at war with Britain and still had a presence in South India, and some of the French craftsmen who visited Tipu's court probably contributed to the internal works of the tiger.[9]

It has been proposed[10] that the design was inspired by the death in 1792 of a son of General Sir Hector Munro, who had commanded a division during Sir Eyre Coote's victory at the Battle of Porto Novo (Parangipettai) in 1781 when Hyder Ali, Tipu Sultan's father, was defeated with a loss of 10,000 men during the Second Anglo-Mysore War.[11] Hector Sutherland Munro, a 17-year-old East India Company Cadet on his way to Madras,[12] was attacked and killed by a tiger on 22 December 1792 while hunting with several companions on Saugor Island in the Bay of Bengal (still one of the last refuges of the Bengal tiger).[13][14][15] However a similar scene was depicted on a silver mount on a gun made for Tipu and dated 1787-88, five years before the incident.[16]

Description

Tipu's Tiger is notable as an example of early musical automata from India,[17] and also for the fact that it was especially constructed for Tipu Sultan.[1]

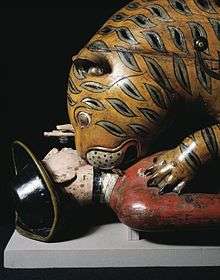

With overall dimensions for the object of 71.2 centimetres (28.0 in) high and 172 centimetres (68 in) long, the man at least is close to life-size.[3] The painted wooden shell forming both figures likely draws upon South Indian traditions of Hindu religious sculpture.[18] It is typically about half an inch thick, and now much reinforced on the inside following bomb damage in World War II. There are many openings at the head end, formed to match the pattern of the inner part of the painted tiger stripes, which allow the sounds from the pipes within to be heard better, and the tiger is "obviously male". The top part of the tiger's body can be lifted off to inspect the mechanics by removing four screws. The construction of the human figure is similar but the wood is much thicker.[19] Examination and analysis by the V&A conservation department has determined that much of the current paint has been restored or overpainted.[20]

The human figure is clearly in European costume, but authorities differ as to whether it represents a soldier or civilian; the current text on the V&A website avoids specifying, other than describing the figure as "European".[21]

The operation of a crank handle powers several different mechanisms inside Tipu's Tiger. A set of bellows expels air through a pipe inside the man's throat, with its opening at his mouth. This produces a wailing sound, simulating the cries of distress of the victim. A mechanical link causes the man's left arm to rise and fall. This action alters the pitch of the 'wail pipe'. Another mechanism inside the tiger's head expels air through a single pipe with two tones. This produces a "regular grunting sound" simulating the roar of the tiger. Concealed behind a flap in the tiger's flank is the small ivory keyboard of a two-stop pipe organ in the tiger's body, allowing tunes to be played.[22]

The style of both shell and workings, and analysis of the metal content of the original brass pipes of the organ (many have been replaced), indicates that the tiger was of local manufacture. The presence of French artisans and French army engineers within Tipu's court has led many historians to suggest there was French input into the mechanism of this automaton.[10]

History

Tipu's Tiger was part of the extensive plunder from Tipu's palace captured in the fall of Seringapatam, in which Tipu died, on 4 May 1799, at the culmination of the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War. An aide-de-camp to the Governor General of the East India Company, Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, wrote a memorandum describing the discovery of the object:[23][24]

"In a room appropriated for musical instruments was found an article which merits particular notice, as another proof of the deep hate, and extreme loathing of Tippoo Saib towards the English. This piece of mechanism represents a royal Tyger in the act of devouring a prostrate European. There are some barrels in imitation of an Organ, within the body of the Tyger. The sounds produced by the Organ are intended to resemble the cries of a person in distress intermixed with the roar of a Tyger. The machinery is so contrived that while the Organ is playing, the hand of the European is often lifted up, to express his helpless and deplorable condition. The whole of this design was executed by Order of Tippoo Sultaun. It is imagined that this memorial of the arrogance and barbarous cruelty of Tippoo Sultan may be thought deserving of a place in the Tower of London."

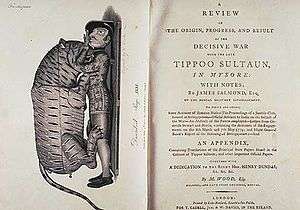

The earliest published drawing of Tippoo's Tyger was the frontispiece for the book "A Review of the Origin, Progress and Result, of the Late Decisive War in Mysore with Notes" by James Salmond, published in London in 1800. It preceded the move of the exhibit from India to England and had a separate preface titled "Description of the Frontispiece" which said:[25]

"This drawing is taken from a piece of mechanism representing a royal tyger in the act of devouring a prostrate European. There are some barrels in imitation of an organ within the body of the tyger, and a row of keys of natural notes. The sounds produced by the organ are intended to resemble the cries of a person in distress, intermixed with the roar of a tyger. The machinery is so contrived, that while the organ is playing, the hand of the European is often lifted up to express his helpless and deplorable condition.

The whole of this design is as large as life, and was executed by order of Tippoo Sultaun, who frequently amused himself with a sight of this emblematic triumph of the Khoodadaud, over the English, Sircar. The piece of machinery was found in a room of the palace at Seringapatam appropriated for the reception of musical instruments, and called the Rag Mehal.

The original wooden figure from which the drawing is taken will be forwarded, by the ships of this season, to the Chairman of the Court of Directors, to be presented to his Majesty. It is imagined that this characteristic emblem of the ferocious animosity of Tippoo Sultaun against the British Nation may not be thought undeserving of a place in the Tower of London."

Unlike Tipu's throne, which also featured a large tiger, and many other treasures in the palace, the materials of Tipu's Tiger had no intrinsic value, which together with its striking iconography is what preserved it and brought it back to England essentially intact. The Governors of the East India Company had at first intended to present the tiger to the Crown, with a view to it being displayed in the Tower of London, but then decided but to keep it for the Company. After some time in store, during which period the first of many "misguided and wholly unjustified endeavours at "improving" the piece" from a musical point of view may have taken place, it was displayed in the reading-room of the East India Company Museum and Library at East India House in Leadenhall Street, London from July 1808.[26][27]

It rapidly became a very popular exhibit, and the crank-handle controlling the wailing and grunting could apparently be freely turned by the public. The French author Gustave Flaubert visited London in 1851 to see the Great Exhibition, writes Julian Barnes, but finding nothing of interest in The Crystal Palace, visited the East India Company Museum where he was greatly enamoured by Tipu's Tiger.[28] By 1843 it was reported that "The machine or organ ... is getting much out of repair, and does not altogether realize the expectation of the visitor".[29] Eventually the crank-handle disappeared, to the great relief of students using the reading-room in which the tiger was displayed, and The Athenaeum later reported that

"These shrieks and growls were the constant plague of the student busy at work in the Library of the old India House, when the Leadenhall Street public, unremittingly, it appears, were bent on keeping up the performances of this barbarous machine. Luckily, a kind fate has deprived him of his handle, and stopped up, we are happy to think, some of his internal organs... and we do sincerely hope he will remain so, to be seen and admired, if necessary, but to be heard no more".[30]

When the East India Company was taken over by the Crown in 1858, the tiger was stored in Fife House, Whitehall until 1868, when it moved down the road to the new India Office, which occupied part of the building still used by today's Foreign and Commonwealth Office. In 1874 it was moved to the India Museum in South Kensington, which was in 1879 dissolved, with the collection distributed between other museums; the V&A records the tiger as acquired in 1880. During World War II the tiger was badly damaged by a German bomb which brought down the roof above it, breaking the wooden casing into several hundred pieces, which were carefully pieced together after the war, so that by 1947 it was back on display. In 1955 it was exhibited in New York at the Museum of Modern Art through the summer and spring.[31][32]

In recent times, Tipu's Tiger has formed an essential part of museum exhibitions exploring the historical interface between Eastern and Western civilisation, colonialism, ethnic histories and other subjects, one such being held at the Victoria and Albert Museum itself in autumn 2004 titled "Encounters:the meeting of Asia and Europe, 1500–1800".[33] In 1995, 'The Tiger and the Thistle' bi-centennial exhibition was held in Scotland on the topic of "Tipu Sultan and the Scots". The organ was considered too fragile to travel to Scotland for the exhibition. Instead, a full-sized replica made of fibre glass and painted by Derek Freeborn, was exhibited in its place. The replica itself also had an earlier Scottish association, having been made in 1986 for 'The Enterprising Scot' exhibition, which was held to commemorate the October 1985 merger of the Royal Scottish Museum and the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland to form a new entity - the National Museum of Scotland.[3]

Today Tipu's Tiger is arguably the best-known single work in the Victoria and Albert Museum as far as the general public is concerned. It is a "must-see" highlight for school-children's visits to the Victoria and Albert Museum, and functions as an iconic representation of the museum, replicated in various forms of memorabilia in the museum shops including postcards, model kits and stuffed toys.[34][34] Visitors can no longer operate the mechanism since the device is now kept in a glass case.

A small model of this toy is exhibited in Tipu Sultan's wooden palace in Bangalore.[35] Although other items associated with Tipu, including his sword, have recently been purchased and brought back to India by billionaire Vijay Mallya,[36] Tipu's Tiger has not itself been the subject of an official repatriation request, presumably due to the ambiguity underlying Tipu's image in the eyes of Indians; his being an object of loathing in the eyes of some Indians while considered a hero by others.[37]:181

Symbolism

Tipu Sultan identified himself with tigers; his personal epithet was 'The Tiger of Mysore,' his soldiers were dressed in 'tyger' jackets, his personal symbol invoked a tiger's face through clever use of calligraphy and the tiger motif is visible on his throne, and other objects in his personal possession, including Tipu's Tiger.[38][39] Accordingly, as per Joseph Sramek, for Tipu the tiger striking down the European in the organ represented his symbolic triumph over the British.[40]

The British hunted tigers, not just to emulate the Mughals and other local elites in this "royal" sport, but also as a symbolic defeat of Tipu Sultan and any other ruler who stood in the path of British domination.[40] The tiger motif was used in the "Seringapatam medal" which was awarded to those who participated in the 1799 campaign, where the British lion was depicted as overcoming a prostrate tiger, the tiger being the dynastic symbol of Tipu's line. The Seringapatam medal was issued in gold for the highest dignitaries who were associated with the campaign as well as select officers on general duty, silver for other dignitaries, field officers and other staff officers, in copper-bronze for the non-commissioned officers and in tin for the privates. On the reverse it had a frieze of the storming of the fort while the obverse showed, in the words of a nineteenth-century tome on medals, "the BRITISH LION subduing the TIGER, the emblem of the late Tippoo Sultan's government, with the period when it was effected and the following words 'ASSUD OTTA-UL GHAULIB', signifying the Lion of God is the conqueror, or the conquering Lion of God."[41]

In this manner, the iconography of this automaton was adopted and overturned by the British.[37]:12, 149 When Tipu's Tiger was displayed in London in the nineteenth century, British viewers of the time "characterised the tiger as a trophy and symbolic justification of British colonial rule".[37] Tipu's Tiger along with other trophies such as Tipu's sword, the throne of Ranjit Singh, Tantya Tope's kurta and Nana Saheb's betel-box which was made of brass, were all displayed as "memorabilia of the Mutiny".[42]

In one interpretation, the display of Tipu's Tiger in South Kensington, served to remind the visitor of the noblesse oblige of the British Empire to bring civilisation to the barbaric lands of which Tipu was king.[43]

Tipu's Tiger is also notable as a literal image of a tiger killing a European, an important symbol in England at the time, and from about 1820 the "Death of Munro" became one of the scenes in the repertoire of Staffordshire pottery figurines.[11][14] Tiger-hunting in the British Raj, is also considered to represent not just the political subjugation of India, but in addition, the triumph over India's environment.[40] The iconography persisted and during the rebellion of 1857, Punch ran a political cartoon showing the Indian rebels as a tiger, attacking a victim in an identical pose to Tipu's Tiger, being defeated by the British forces shown by the larger figure of a lion.

The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, August 15, 1835[44]

It has been suggested that Tipu’s Tiger also contributed indirectly to the development of a popular early-20th-century stereotype of China as the "Sleeping Lion". A recent study describes how this popular stereotype actually drew on Chinese reports about the tiger[45]

Motives for collection of articles, such as Tipu's Tiger, are seen by literary historian Barrett Kalter as having a social and cultural context.[46] The collection of Western and Indian art by Tipu Sultan is seen by Kalter as motivated by the need to display his wealth and legitimise his authority over his subjects who were predominantly Hindu and did not share his religion, viz. Islam.[46] In the case of the East India Company, collection of documents, artefacts and objet's d'art from India helped develop the idea of a subjugated Indian populace in the minds of the British people, the thought being that the possession of such objects of a culture represented understanding of, dominance over, and mastery of that culture.[46]

As a musical instrument

In a detailed study published in 1987 of the tiger's musical and noise-making functions, Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume concluded that since coming to Britain, "the instrument has been ruthlessly reworked, and in doing so much of its original operating principles have been destroyed".[47] There are two ranks of pipes in the organ (as opposed to the wailing and grunting functions), each "comprising eighteen notes, [which] are nominally of 4ft pitch and are unisons - i.e. corresponding pipes in each register make sounds of the same musical pitch. This is an unusual layout for a pipe organ although while selecting the two stops together results in more sound ... there is also detectable a slight beat between the pipes so creating a celeste effect. ... it is considered likely that as so much work has been done ... this characteristic may be more an accident of tuning than an intentional feature".[48] The tiger's grunt is made by a single pipe in the tiger's head and the man's wail by a single pipe emerging at his mouth and connected to separate bellows located in the man's chest, where they can be accessed by unbolting and lifting off the tiger. The grunt operates by cogs gradually raising the weighted "grunt-pipe" until it reaches a point where it slips down "to fall against its fixed lower-board or reservoir, discharging the air to form the grunting sound"[49] Today all the sound-making functions rely on the crank-handle to power them, though Ord-Hume believes this was not originally the case.[19]

Works on the noise-making functions included those made over several decades by the famous organ-building firm Henry Willis & Sons, and Henry Willis III, who worked on the tiger in the 1950s, contributed an account to a monograph by Mildred Archer of the V&A. Ord-Hume is generally ready to exempt Willis work from his scathing comments on other drastic restorations, which "vandalism" is assumed to be by unknown earlier organ-builders.[50] There was a detailed account of the sound-making functions in The Penny Magazine in 1835, whose anonymous author evidently understood "things mechanical and organs in particular".[51] From this and Ord-Hume's own investigations, he concluded that the original operation of the man's "wail" had been intermittent, with a wail only being produced after every dozen or so grunts from the tiger above, but that at some date after 1835 the mechanism had been altered to make the wail continuous, and that the bellows for the wail had been replaced with smaller and weaker ones, and the operation of the moving arm altered.[19][52]

Puzzling features of the present instrument include the placing of the handle, which when turned is likely to obstruct a player of the keyboard.[53] Ord-Hume, using the 1835 account, concludes that originally the handle (which is a nineteenth-century British replacement, probably of a French original) only operated the grunt and wail, while the organ was operated by pulling a string or cord to work the original bellows, now replaced.[54] The keyboard, which is largely original, is "unique in construction", with "square ivory buttons" with round lathe-turned tops instead of conventional keys. Though the mechanical functioning of each button is "practical and convenient" they are spaced such that "it is almost impossible to stretch the hand to play an octave".[55] The buttons are marked with small black spots, differently placed but forming no apparent pattern in relation to the notes produced and corresponding to no known system of marking keys.[56] The two stop control knobs for the organ are located, "rather confusingly", a little below the tiger's testicles.[57] The instrument is now rarely played, but there is a V&A video of a recent performance.[58]

Derivative works

Tipu's Tiger has provided inspiration to poets, sculptors, artists and others from the nineteenth century to the present day.[59] The poet John Keats saw Tipu's Tiger at the museum in Leadenhall Street and worked it into his satirical verse of 1819, The Cap and Bells.[59] In the poem, a soothsayer visits the court of the Emperor Elfinan. He hears a strange noise and thinks the Emperor is snoring.[60]

- "Replied the page: “that little buzzing noise….

- Comes from a play-thing of the Emperor’s choice,

- From a Man-Tiger-Organ, prettiest of his toys"

The French poet, Auguste Barbier, described the tiger and its workings and meditated on its meaning in his poem, Le Joujou du Sultan (The Plaything of the Sultan) published in 1837.[61][62] More recently, the American Modernist poet, Marianne Moore wrote in her 1967 poem Tippoo's Tiger about the workings of the automaton,[63] though in fact the tail was never movable:

- "The infidel claimed Tipu's helmet and cuirasse

- and a vast toy - a curious automaton

- a man killed by a tiger; with organ pipes inside

- from which blood-curdling cries merged with inhuman groans.

- The tiger moved its tail as the man moved his arm."

Die Seele (The Souls), a work by painter Jan Balet (1913–2009), shows an angel trumpeting over a flower garden while a tiger devours a uniformed French soldier.[59] The Indian painter M. F. Husain painted Tipu's Tiger in his characteristic style in 1986 titling the work as "Tipu Sultan's Tiger".[64] The sculptor Dhruva Mistry, when a student at the Royal College of Art, adjacent to the Victoria and Albert Museum, frequently passed Tipu's Tiger in its glass case and was inspired to make a fibre-glass and plastic sculpture Tipu in 1986.[59] The sculpture Rabbit eating Astronaut (2004) by the artist Bill Reid is a humorous homage to the tiger, the rabbit "chomping" when its tail is cranked round.[65]

Notes

- Victoria & Albert Museum (2011). "Tipu's Tiger". London: Victoria & Albert Museum. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Ivan; Corinne A. (2000). "Reflections on the fate of Tippoo's Tiger - Defining cultures through public display". In Hallam, Elizabeth (ed.). Cultural encounters: representing otherness. Street, Brian V. Routledge. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-415-20280-0. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Unattributed (2000). "1.1 Tippoo's Tiger". The Tiger and the Thistle - Tipu Sultan and the Scots in India. The National Galleries of Scotland. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Brittlebank, K. (1995). "Sakti and Barakat: The Power of Tipu's Tiger. An Examination of the Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of Mysore". Modern Asian Studies. 29 (2): 257–269. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00012725. JSTOR 312813.

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, p. 23.

- Davis, 156-157 on the throne, and 153-157 on the prize fund generally

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, pp. 23-24.

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, p. 24.

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, pp. 24-25.

- Archer, Mildred (1959). Tippoo's Tiger. Museum Monograph, Victoria & Albert Museum. London: HM Stationery Office. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, p. 26.

- Munro, Colin (4 January 2018). "Thus were the British defeated". London Review of Books. 40: 20–21.

- Victoria & Albert Museum (2011). "Tipu's Tiger Sound and Movement animation". London: Victoria & Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- de Almeida, 38

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, pp. 25-26.

- Susan., Stronge (2009). Tipu's tigers. Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V & A Publishing. ISBN 978-1851775750. OCLC 317927180.

- Angelika (21 November 2009). "Part 13. The First Portable Music Player – The Most Popular Automatic Music Instrument in the World". The Race Music. theracemusic.net. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2011.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Stronge, Susan (2009). Tipu's Tigers. London: V & A Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-85177-575-0. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, p. 66.

- V&A Conservation in Action - Tippoo's Tiger video, accessed, 17 July 2011

- Tippoo's Tiger on Victoria & Albert Museum website Archived 25 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine; to Ord-Hume he is "a European soldier" (Part 1, 21), but to de Almeida and Gilpin he is "an English gentleman" (p. 35)

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, summarized at p. 64 and throughout in more detail.

- The St James's Chronicle, April 1800; also reported in the Edinburgh Caledonian Mercury 24 April 1800.

- Stronge 2009, p. 62

- As quoted in Wood, Col Mark (2000). "2.4 Tippoo's Tiger: Frontispiece". The Tiger and the Thistle - Tipu Sultan and the Scots in India. The National Galleries of Scotland. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Ord-Hume, 1987a, pp. 29-31.

- 153-157

- Pritchett, Prof Frances W. (2000). "Symbols". Tipu Sultan of Mysore (r. 1782-99). Columbia University. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, 79

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, 79, quoting The Athenaeum, June 5, 1869, p. 766

- Ord-Hume, Part 1, 31

- Mann, Phyllis G. (1957). "News and Notes". Keats-Shelley Journal. 6: 9–12. JSTOR 30210016.

- Jaffer, Amin (January 2007). "Histories from the Sea: Use of Images, Video and Audio Materials as Tools for Understanding and Teaching South Asia-Europe Maritime History" (PDF). In Gomes, Francisco José (ed.). Histories from the Sea - Proceedings of International Conference 30–31 January 2007. Alexandra Curvelo, Clare Anderson, Bhaswati Bhattacharya, Kévin Le Doudic, Momin Chaudhury, Samuel Berthet, Bhagwan S. Josh & K. Madavane. New Delhi: Centre for French and Francophone Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawarharlal Nehru University. pp. 27–35. Archived from the original (pdf) on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Kromm, Jane; Bakewell, Susan Benforado (2 February 2010). A history of visual culture: Western civilization from the 18th to the 21st century. Berg. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-84520-492-1. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ECity Bangalore (2011). "Tipu Sultan's Fort and Palace". Archived from the original on 9 December 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Singh, Kishore (10 December 2009). "In search of Tipu's wealth". Business Standard. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Davis, Richard H. (1999). Lives of Indian Images. American Council of Learned Societies. Princeton University Press. pp. 150–157, 178–185. ISBN 978-0-691-00520-1. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Unattributed (2000). "1.0 Tiger Introduction". The Tiger and the Thistle - Tipu Sultan and the Scots in India. The National Galleries of Scotland. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Walsh, Robin (1999). "Images - Tiger Motif". Seringapatam 1799: letters and journals of Lachlan Macquarie in India. McQuarrie University. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Sramek, Joseph (Summer 2006). ""Face Him Like a Briton": Tiger Hunting, Imperialism, and British Masculinity in Colonial India, 1800-1875". Victorian Studies. 48 (4): 659–680. doi:10.1353/vic.2007.0035 (inactive 21 May 2020). ISSN 0042-5222.

- Carter, Thomas (1893). War medals of the British army, and how they were won (War medals of the British army, and how they were won. ed.). London: Norie and Wilson. OL 14047956M.

- Neela (1 January 1999). "Displaying histories - Museums and the Politics of Culture". In Dossal, Mariam (ed.). State intervention and popular response: western India in the nineteenth century. Maloni, Ruby. Popular Prakashan. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-7154-855-2. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Yallop, Jacqueline (1 April 2010). Magpies, Squirrels and Thieves: How the Victorians Collected the World. Atlantic Books, Limited. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-84354-750-1. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Knight, Charles; Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain) (1834). The penny magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Charles Knight. p. 320. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Ari Larissa Heinrich, Chinese Surplus: Biopolitical Aesthetics and the Medically Commodified Body, Ch. 1, (Duke, 2018)

- Kalter, Barrett (2008). "Review Essay: "Shopping, Collecting, and Feeling at Home"". Eighteenth-Century Fiction. 20 (3, Article 11): 469–477. doi:10.1353/ecf.0.0008. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Ord-Hume, Part 1, 31, though his main discussion of the matter is in his Part 2.

- Ord-Hume, 1987b, p. 69.

- Ord-Hume, 1987b, pp. 64-66, photos 67-68.

- Ord-Hume, Part 1, 30, and Part 2 passim

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, 75, preceding his full reproduction of the text.

- video of David Dimbleby playing the grunt and wail only

- Ord-Hume, Part 1, 21

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, 71, 73, 75, 77, and see videos linked at the end of the section

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, 69, 73, and see videos linked at the end of the section

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, 69, and see videos linked at the end of the section

- Ord-Hume, Part 2, 64

- Vimeo.com Conservation in Action - Playing Tippoo's Tiger Part 2, and Part 1, with the top of the tiger removed, accessed 17 July 2011

- Unattributed (2000). "3.43 Tiger Buckle". The Tiger and the Thistle - Tipu Sultan and the Scotts in India. The National Galleries of Scotland. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Radcliffe, David A. "The Cap and Bells; or, the Jealousies, a Faery Tale. Unfinished. - John Keats". Department of English, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. Retrieved 18 July 2011.. Dead website, retrieved through The Wayback Machine

- Unattributed (2000). "2.5 Tippoo's Tiger: On Show, Leadenhall St Museum". The Tiger and the Thistle - Tipu Sultan and the Scotts in India. The National Galleries of Scotland. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Text of Le Joujou du Sultan, from Auguste Barbier, Iambes et poèmes, published E. Dentu, 1868.

- Vincent, John (2002). "The Magician's Advance : Late Moore". Queer lyrics: difficulty and closure in American poetry. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-312-29497-7. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Unattributed (15 June 2010). "Lot 46 HUSAIN Maqbool Fida, *1915 (India)". Art, Luxe and Collection. artvalue.com. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Illustrated Stronge, p.89; beebomb.com here Archived 27 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Brittlebank, Kate (May 1995), "Sakti and Barakat: The Power of Tipu's Tiger. An Examination of the Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of Mysore", Modern Asian Studies, 29 (2): 257–269, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00012725, JSTOR 312813

- De Almeida, Hermione; Gilpin, George H. (2005), Indian Renaissance: British romantic art and the prospect of India, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7546-3681-6, retrieved 16 July 2011

- Ord-Hume, Arthur (1987), "Tipu's Tiger - its History and Description - Part I", Music and Automata, 3 (9)

- Ord-Hume, Arthur (1987), "Tipu's Tiger - its History and Description - Part II", Music and Automata, 3 (10)

- Stronge, Susan (2009), Tipu's Tigers, V&A Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85177-575-0

Videos of the tiger in performance

- Video of David Dimbleby playing the grunt and wail only.

- V&A video of a recent performance of the organ from Vimeo.com: Conservation in Action - Playing Tipu's Tiger Part 2, and Part 1, with the top of the tiger removed.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tipu's Tiger. |

- Accession page for Tipu's Tiger on Victoria & Albert Museum website

- Article on Tipu's Tiger on Victoria & Albert Museum website

- Sound and Movement animation at the Victoria & Albert Museum web site

- Tiger - Decorative motif & symbol of Tipu Sultan

- Tipu biography & Mysore history

- Death of Munrow c. 1814

- Discussion by Janina Ramirez and Sona Datta of Peabody Essex Museum: Art Detective Podcast, 17 Mar 2017