Til Barsip

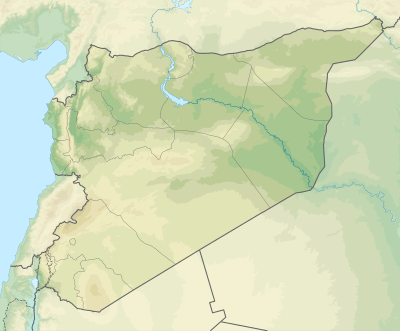

Til Barsip or Til Barsib (Hittite Masuwari,[1] modern Tell Ahmar; Arabic: تل أحمر) is an ancient site situated in Aleppo Governorate, Syria by the Euphrates river about 20 kilometers south of ancient Carchemish.

تل أحمر | |

Shown within Syria | |

| Alternative name | Tell Ahmar |

|---|---|

| Location | Syria |

| Region | Aleppo Governorate |

| Coordinates | 36.674°N 38.121°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 50 hectares (120 acres) |

| History | |

| Periods | Assyrian |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Management | Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums |

| Public access | Yes |

History

The site was inhabited as early as the Neolithic period, but it is the remains of the Iron Age city which is the most important settlement at Tell Ahmar. It was known in Hittite as Masuwari.[1][2] The city remained largely Neo-Hittite up to its conquest by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 856 BC and the Luwian language was used even after that.[3][4] Til Barsip was in the area of the Aramean-speaking Syro-Hittite state of Bît Adini. After being captured by the Assyrians the city was then renamed as Kar-Šulmānu-ašarēdu, after the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, though its original name continued in use. It became a prominent center for the Assyrian administration of the region due to its strategic location at a crossing of the Euphrates river.

Archaeology

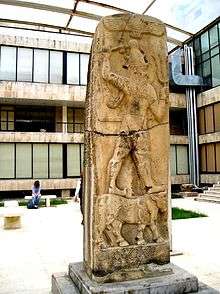

The tell was first examined by David George Hogarth, who proposed the identification as Til Barsip.[5] The site was visited in 1909 by Gertrude Lowthian Bell who also took squeezes from some of the inscriptions there.[6][7] The site of Tell Ahmar was excavated by the French archaeologist François Thureau-Dangin from 1929 to 1931.[8][9] He uncovered the Iron Age city and an Early Bronze Age hypogeum burial with a large amount of pottery. Three important steles were also discovered at the site. These record how the 8th century BC Aramean king Bar Ga'yah, who may be identical with the Assyrian governor Shamshi-ilu, made a treaty with the city of Arpad. Recent excavations at Tell Ahmar were conducted by Guy Bunnens from the University of Melbourne in the late 1980s and through to the present.[10][11][12][13] Excavations ended in 2010.[14] Many ivory carvings of outstanding quality were discovered and these were published in 1997. Current excavations are under the auspices of the University of Liège, Belgium.[15]

Ahmar/Qubbah stele

Among the early Iron Age monuments discovered in the area was a particularly well-preserved stele known as the Ahmar/Qubbah stele, inscribed in Luwian,[12] which commemorates a military campaign by king Hamiyatas of Masuwari around 900 BC. The stele also attests to the continued cult of the deity 'Tarhunzas of the Army', whom Hamiyatas is thought to have linked with Tarhunzas of Heaven and with the Storm-God of Aleppo.[16] This stele also indicates that the first king of Masuwari was named Hapatila, which may represent an old Hurrian name Hepa-tilla.

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Short chronology timeline

Notes

- Hawkins, John D. Inscriptions of the Iron Age. Retrieved 7 Dec. 2010.

- J. D. Hawkins, The Hittite Name of Til Barsip: Evidence from a New Hieroglyphic Fragment from Tell Ahmar, Anatolian Studies, vol. 33, Special Number in Honour of the Seventy-Fifth Birthday of Dr. Richard Barnett, pp. 131-136, 1983

- J. D. Hawkins, The "Autobiography of Ariyahinas's Son": An Edition of the Hieroglyphic Luwian Stelae Tell Ahmar 1 and Aleppo 2, Anatolian Studies, vol. 30, Special Number in Honour of the Seventieth Birthday of Professor O. R. Gurney, pp. 139-156, 1980

- Fred C. Woudhuizen, The Recently Discovered Luwian Hieroglyphic Inscription from Tell Ahmar, Ancient West & East, vol. 9, pp. 1-19, 2010

- D. G. Hogarth, Recent Hittite Research, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 39, pp. 408-415, 1909

- Gertrude Lowthian Bell, The East Bank of the Euphrates from Tel Ahmar to Hit, The Geographical Journal, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 513-537, 1910

- Gertrude Lowthian Bell, Amurath to Amurath, W. Heinemann, 1911

- François Thureau-Dangin, Tell-Ahmar, Syria, vol. 10, iss. 10-3, pp. 185-205, 1929

- F Thureau-Dangin; Maurice Dunand; Lucien Cavro; Georges Dossin, Til-Barsib, Paris : Paul Geuthner, 1936

- Guy Bunnens, Tell Ahmar, 1988 Season, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement Series, vol. 2, Peeters, 1990, ISBN 978-90-6831-322-2

- Guy Bunnens, Melbourne University Excavations at Tell Ahmar on the Euphrates. Short Report on the 1989-1992 Seasons, Akkadica, no. 79-80, pp. 1-13, 1992

- Bunnens, Guy; Hawkins, J.D.; Leirens, I. (2006). A New Luwian Stele and the Cult of the Storm-God at Til Barsib-Masuwari. Tell Ahmar II. Leuven: Publications de la Mission archéologique de l'Université de Liège en Syrie, Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1817-7.

- A. Jamieson, Tell Ahmar III. Neo-Assyrian Pottery from Area C, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement Series, vol. 35, Peeters, 2011, ISBN 978-90-429-2364-5

- Guy Bunnens, A 3rd millennium temple at Tell Ahmar (Syria)_Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East 3, Reports, ed. Oskar KAELIN & Hans-Peter MATHYS, Wiesbaden, pp. 187-198, 2016

- Guy Bunnens, Tell Ahmar / Til Barsib, The Fourteenth and Fifteenth seasons (2001/2002), Orient Express, pp. 40-43, 2003

- Bunnens, Guy (2006). "Religious Context". A New Luwian Stele and the Cult of the Storm-God at Til Barsib-Masuwari. Tell Ahmar II. Leuven: Publications de la Mission archéologique de l'Université de Liège en Syrie, Peeters. pp. 76–81. ISBN 978-90-429-1817-7.

References

- Guy Bunnens, "Carved ivories from Til Barsib", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 101, no.3, pp. 435–450, (July 1997). Online version by JSTOR

- Arlette Roobaert, "A Neo-Assyrian Statue from Til Barsib", Iraq, vol. 58, pp. 79–87, 1996

- Stephanie Dalley, "Neo-Assyrian Tablets from Til Barsib", Abr-Nahrain, vol. 34, pp. 66–99, 1996–1997

- Pierre Bordreuil and Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet, "Aramaic Documents from Til Barsip", Abr-Nahrain, vol. 34, pp. 100–107, 1996–1997

- R. Campbell Thompson, "Til-Barsip and Its Cuneiform Inscriptions", PSBA, vol. 34, pp. 66–74, 1912.

- Arlette Roobaert, "The Middle Bronze Age Funerary Evidence from Tell Ahmar (Syria)", Ancient Near Eastern Studies, vol. 35, pp. 97–105, 1998

- Max E.L. Mallowan, "The Syrian City of Til-Barsib", Antiquity, vol. 11, pp. 328–39, 1937

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Til Barsip. |