Tibúrcio Spannocchi

Tiburzio Spannocchi (1541–1609) (also Spanucchi, Spanochi, Spanoqui, Hispanochi etc.) was "king's engineer" to Philip II of Spain and subsequently to Philip III of Spain. He was named "Chief Engineer" in 1601.[1]

Tiburzio Spannocchi | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1541 |

| Died | 1609 |

| Nationality | Siennese, Spanish |

| Occupation | Military Engineer |

| Known for | Chief engineer to Philip III of Spain |

Origins

Tiburzio Spannocchi was an engineer from Siena.[2][lower-alpha 1] He was born in 1541.[1] He came from a noble Tuscan family, and served the Papal States in the fleet commanded by Marcantonio Colonna. In 1575 he was sent to Sicily as a Viceroy. Spannocchi entered the service of the King of Spain around 1580.[4]

Engineering works

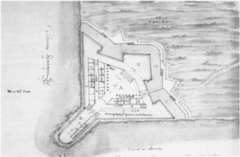

Spannocchi became involved in a project to control the Strait of Magellan.[4] Two forts were to be placed on either side of the start of the first narrows (Primera Angostura) on the Punta Anegada and Punta Delgada, creating an impregnable position.[2] A chain could be slung between the two forts to prevent any ships from passing.[5] Experts agreed that the bastions were extremely efficient in their design.[5] However, the project was abandoned when it was realized that many ships would simply bypass the Strait by sailing round Cape Horn.[4]

Spannocchi worked at Havana between 1586 and 1587, and may have worked at San Juan and Cartagena.[4] In 1588 Spannocchi approved plans for the forts of El Morro and La Punta at Havana, Cuba as senior engineer to King Philip II.[6] Philip II had commissioned the engineer Giovan Giacomo Paleari Fratino to strengthen the Fortifications of Gibraltar. Fratino proposed to destroy the work done on a wall started by his predecessor, Giovanni Battista Calvi, but Spannocchi refused to stop work on the zigzag wall, which was eventually finished in 1599, and is the upper portion of what is now called the Charles V Wall.[7]

Spannocchi undertook various works on the citadel of Aljafería in Zaragoza for which Philip II himself had traced the drawing.[3] Philip II gave him a commission to fortify the palace and transform it into a citadel. He executed the work in 1593, building the fortress of bricks and mortar with cornerstones, and surrounding it by a moat. The two doors were elaborately decorated. After these changes, the Aljafería was used as a military installation until the middle of the 20th century.[8]

Later Spannocchi's main energy went into mapping sites in the Pyrenees along the frontier between Spain and France, during a period of mounting tension between the two countries.[4] The citadel of Jaca was built in the shape of a pentagon under his direction.[9] In 1598 he advocated construction of a small fort to guard the entrance to the port of Pasaia, but planning did not start until 1620.[10] At the start of the 17th century, Spannochi and Jerónimo de Soto were involved in construction of the palace of La Ventosilla in Burgos, including a supply of running water and other features that would contribute to greater comfort.[11]

Spannocchi designed the nine-sided Fortaleza da Lage de São Francisco that defended Recife from the seas, and the Forte do Mar de São Marcelo that defended Salvador da Bahia. The plans for these two forts were sent to Brazil in May 1606.[12] Tibúrcio Spannocchi died in 1609.[1]

Influence

In 1582 Spannocchi and Juan de Herrera founded the Department of Mathematical Military Architecture under the patronage of Philip II, an important school for training military engineers and architects.[13] Jerónimo de Soto was one of Spannocchi's disciples.[14] Another of his pupils was Cristóbal de Rojas, known for working as an assistant to Juan de Herrera in the construction of the monastery of El Escorial. Rojas worked as Spannocchi's deputy and became especially interested in military architecture, undertaking major works in Spain and North Africa. Rojas was the author of Teórica y práctica de la fortificación ("Theory and practice of fortification"), published in 1598, the first book on the science of fortification published in Spain. It was essentially a compendium of lessons from the Madrid Academy of Mathematics. The text highlights the influence of the Italian School's polygonal and radio-concentric theories.[15]

References

Notes

Citations

- Alarcón Pérez 2011, p. 28.

- Ortega 2011, p. 224.

- Mignet & Pérez 1881, p. 307.

- Reinhartz & Saxon 2005, p. 47.

- Ortega 2011, p. 225.

- Marley 2008, p. 132.

- Chipulina 2012.

- Drawing of the Aljaferia...

- Hidalgo, Hidalgo & Piera 1864, p. 58.

- St. Elizabeth's castle.

- Varea 2007, p. 140.

- Bethell 1984, p. 749.

- Cámara Muñoz 1998, p. 102.

- Losada Varea 2007, p. 268.

- González 2009, p. 63.

Sources

- Alarcón Pérez, Enrique (December 2011). EL OCHOCIENTOS De los lenguajes al patrimonio. TÉCNICA E INGENIERÍA EN ESPAÑA VI. Universidad de Zaragoza. ISBN 978-84-9911-151-3. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bethell, Leslie (1984-12-06). The Cambridge History of Latin America. Cambridge University Press. p. 749. ISBN 978-0-521-24516-6. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chipulina, Neville (2012). "1740 – Skinner's Moorish Wall". Retrieved 2012-10-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Drawing of the Aljaferia Palace in Zaragoza, from the east". Ministry of Education. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- González, María Soledad Pita (2009). Referencias a la arquitectura civil en tratados de Fortificación de los siglos XVI al XVIII. Cultivalibros. ISBN 978-84-9923-060-3. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hidalgo, Dionisio; Hidalgo, Manual Fernandez; Piera, Arturo (1864). Boletín bibliográfico español. las escuelas Pias. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Losada Varea, Celestina (2007). La Arquitectura en el Otoño Del Renacimiento: Juan de Naveda 1590–1638. Ed. Universidad de Cantabria. p. 268. ISBN 978-84-8102-438-8. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marley, David (2008-02-28). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-100-8. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mignet, François-Auguste–Marie–Alexis; Pérez, Antonio (1881). Antonio Perez et Philippe II. Didier. p. 307. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cámara Muñoz, Alicia (1998). Fortificación y Ciudad en Los Reinos de Felipe II. Editorial NEREA. ISBN 9788489569263.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ortega, Adolfo García (2011-10-06). Desolation Island. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4464-6824-1. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reinhartz, Dennis; Saxon, Gerald D. (2005-10-01). Mapping and Empire: Soldier-Engineers on the Southwestern Frontier. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70659-0. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "St. Elizabeth's castle". Departamento de Cultura, Juventud y Deporte. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- Varea, Celestina Losada (2007). La Arquitectura en el Otoño Del Renacimiento: Juan de Naveda 1590–1638. Ed. Universidad de Cantabria. ISBN 978-84-8102-438-8. Retrieved 2012-10-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)