Thymus

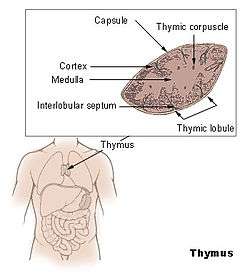

The thymus is a specialized primary lymphoid organ of the immune system. Within the thymus, Thymus cell lymphocytes or T cells mature. T cells are critical to the adaptive immune system, where the body adapts specifically to foreign invaders. The thymus is located in the upper front part of the chest, in the anterior superior mediastinum, behind the sternum, and in front of the heart. It is made up of two lobes, each consisting of a central medulla and an outer cortex, surrounded by a capsule.

| Thymus | |

|---|---|

Thymus | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Third pharyngeal pouch |

| System | Lymphatic system, part of the immune system |

| Lymph | tracheobronchial, parasternal |

| Function | Support the development of functional T cells |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Thymus |

| MeSH | D013950 |

| TA | A13.1.02.001 |

| FMA | 9607 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The thymus is made up of immature T cells called thymocytes, as well as lining cells called epithelial cells which help the thymocytes develop. T cells that successfully develop react appropriately with MHC immune receptors of the body (called positive selection,) and not against proteins of the body, (called negative selection). The thymus is largest and most active during the neonatal and pre-adolescent periods. By the early teens, the thymus begins to decrease in size and activity and the tissue of the thymus is gradually replaced by fatty tissue. Nevertheless, some T cell development continues throughout adult life.

Abnormalities of the thymus can result in a decreased number of T cells and autoimmune diseases such as Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 and myasthenia gravis. These are often associated with cancer of the tissue of the thymus, called thymoma, or tissues arising from immature lymphocytes such as T cells, called lymphoma. Removal of the thymus is called thymectomy. Although the thymus has been identified as a part of the body since the time of the Ancient Greeks, it is only since the 1960s that the function of the thymus in the immune system has become more clear.

Structure

The thymus is an organ that sits beneath the sternum in the upper front part of the chest, stretching upwards towards the neck. In children, the thymus is pinkish-gray, soft, and lobulated on its surfaces.[1] At birth it is about 4–6 cm long, 2.5–5 cm wide, and about 1 cm thick.[2] It increases in size until puberty, where it may have a size of about 40–50 g,[3][4] following which it decreases in size in a process known as involution.[4]

The thymus is made up of two lobes that meet in the upper midline, and stretch from below the thyroid in the neck to as low as the cartilage of the fourth rib.[1] The lobes are covered by a capsule.[3] The thymus lies beneath the sternum, rests on the pericardium, and is separated from the aortic arch and great vessels by a layer of fascia. The left brachiocephalic vein may even be embedded within the thymus.[1] In the neck, it lies on the front and sides of the trachea, behind the sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles.[1]

Microanatomy

The thymus consists of two lobes, merged in the middle, surrounded by a capsule that extends with blood vessels into the interior.[2] The lobes consist of an outer cortex rich with cells and an inner less dense medulla.[4] The lobes are divided into smaller lobules 0.5-2mm diameter, between which extrude radiating insertions from the capsule along septa.[1]

The cortex is mainly made up of thymocytes and epithelial cells.[3] The thymocytes, immature T cells, are supported by a network of the finely-branched epithelial reticular cells, which is continuous with a similar network in the medulla. This network forms an adventitia to the blood vessels, which enter the cortex via septa near the junction with the medulla.[1] Other cells are also present in the thymus, including macrophages, dendritic cells, and a small amount of B cells, neutrophils and eosinophils.[3]

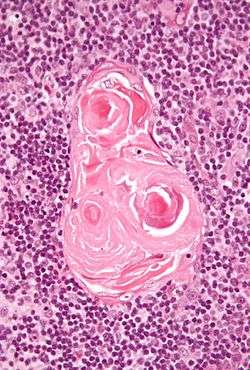

In the medulla, the network of epithelial cells is coarser than in the cortex, and the lymphoid cells are relatively fewer in number.[1] Concentric, nest-like bodies called Hassall's corpuscles (also called thymic corpuscles) are formed by aggregations of the medullary epithelial cells.[3] These are concentric, layered whorls of epithelial cells that increase in number throughout life.[1] They are the remains of the epithelial tubes, which grow out from the third pharyngeal pouches of the embryo to form the thymus.[5]

- Micrograph showing a lobule of the thymus. The cortex (deeper purple area) surrounds a less dense and lighter medulla.

Micrograph showing a Hassall's corpuscle, found within the medulla of the thymus.

Micrograph showing a Hassall's corpuscle, found within the medulla of the thymus.

Blood and nerve supply

The arteries supplying the thymus are branches of the internal thoracic, and inferior thyroid arteries, with branches from the superior thyroid artery sometimes seen.[2] The branches reach the thymus and travel with the septa of the capsule into the area between the cortex and medulla, where they enter the thymus itself; or alternatively directly enter the capsule.[2]

The veins of the thymus end in the left brachiocephalic vein, internal thoracic vein, and in the inferior thyroid veins.[2] Sometimes the veins end directly in the superior vena cava.[2]

Lymphatic vessels travel only away from the thymus, accompanying the arteries and veins. These drain into the brachiocephalic, tracheobronchial and parasternal lymph nodes.[2]

The nerves supplying the thymus arise from the vagus nerve and the cervical sympathetic chain.[2] Branches from the phrenic nerves reach the capsule of the thymus, but do not enter into the thymus itself.[2]

Development

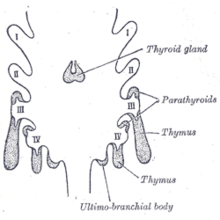

The thymocytes and the epithelium of the thymus have different developmental origins.[4] The epithelium of the thymus develops first, appearing as two outgrowths, one on either side, of the third pharyngeal pouch.[4] It sometimes also involves the fourth pharyngeal pouch.[3] These extend outward and backward into the surrounding mesoderm and neural crest-derived mesenchyme in front of the ventral aorta. Here the thymocytes and epithelium meet and join with connective tissue. The pharyngeal opening of each diverticulum is soon obliterated, but the neck of the flask persists for some time as a cellular cord. By further proliferation of the cells lining the flask, buds of cells are formed, which become surrounded and isolated by the invading mesoderm.[6]

The epithelium forms fine lobules, and develops into a sponge-like structure. During this stage, hematopoietic bone-marrow precursors migrate into the thymus.[4] Normal development is dependent on the interaction between the epithelium and the hematopoietic thymocytes. Iodine is also necessary for thymus development and activity.[7]

Involution

The thymus continues to grow after the birth reaching the relative maximum size by puberty.[2] It is most active in fetal and neonatal life.[8] It increases to 20 - 50 grams by puberty.[3] It then begins to decrease in size and activity in a process called thymic involution.[4] After the first year of life the amount of T cells produced begins to fall.[4] Fat and connective tissue fills a part of the thymic volume.[2] During involution, the thymus decreases in size and activity.[4] Fat cells are present at birth, but increase in size and number markedly after puberty, invading the gland from the walls between the lobules first, then into the cortex and medulla.[4] This process continues into old age, where whether with a microscope or with the human eye, the thymus may be difficult to detect,[4] although typically weights 5 - 15 grams.[3]

The atrophy is due to the increased circulating level of sex hormones, and chemical or physical castration of an adult results in the thymus increasing in size and activity.[9] Severe illness or human immunodeficiency virus infection may also result in involution.[3]

Function

T cell maturation

The thymus facilitates the maturation of T cells, an important part of the immune system providing cell-mediated immunity.[10] T cells begin as hematopoietic precursors from the bone-marrow, and migrate to the thymus, where they are referred to as thymocytes. In the thymus they undergo a process of maturation, which involves ensuring the cells react against antigens ("positive selection"), but that they do not react against antigens found on body tissue ("negative selection").[10] Once mature, T cells emigrate from the thymus to provide vital functions in the immune system.[10][11]

Each T cell has a distinct T cell receptor, suited to a specific substance, called an antigen.[11] Most T cell receptors bind to the major histocompatibility complex on cells of the body. The MHC presents an antigen to the T cell receptor, which becomes active if this matches the specific T cell receptor.[11] In order to be properly functional, a mature T cell needs to be able to bind to the MHC molecule ("positive selection"), and not to react against antigens that are actually from the tissues of body ("negative selection").[11] Positive selection occurs in the cortex and negative selection occurs in the medulla of the thymus.[12] After this process T cells that have survived leave the thymus, regulated by sphingosine-1-phosphate.[12] Further maturation occurs in the peripheral circulation.[12] Some of this is because of hormones and cytokines secreted by cells within the thymus, including thymulin, thymopoietin, and thymosins.[4]

Positive selection

T cells have distinct T cell receptors. These distinct receptors are formed by process of V(D)J recombination gene rearrangement stimulated by RAG1 and RAG2 genes.[12] This process is error-prone, and some thymocytes fail to make functional T-cell receptors, whereas other thymocytes make T-cell receptors that are autoreactive.[13] If a functional T cell receptor is formed, the thymocyte will begin to express simultaneously the cell surface proteins CD4 and CD8.[12]

The survival and nature of the T cell then depends on its interaction with surrounding thymic epithelial cells. Here, the T cell receptor interacts with the MHC molecules on the surface of epithelial cells.[12] A T cell with a receptor that doesn't react, or reacts weakly will die by apoptosis. A T cell that does react will survive and proliferate.[12] A mature T cell expresses only CD4 or CD8, but not both.[11] This depends on the strength of binding between the TCR and MHC class 1 or class 2.[12] A T cell receptor that binds mostly to MHC class I tends to produce a mature "cytotoxic" CD8 positive T cell; a T cell receptor that binds mostly to MHC class II tends to produces a CD4 positive T cell.[13]

Negative selection

T cells that attack the body's own proteins are eliminated in the thymus, called "negative selection".[11] Epithelial cells in the medulla and dendritic cells in the thymus express major proteins from elsewhere in the body.[12] The gene that stimulates this is AIRE.[11][12] Thymocytes that react strongly to self antigens do not survive, and die by apoptosis.[11][12] Some CD4 positive T cells exposed to self antigens persist as T regulatory cells.[11]

Clinical significance

Immunodeficiency

As the thymus is where T cells develop, congenital problems with the development of the thymus can lead to immunodeficiency, whether because of a problem with the development of the thymus gland, or a problem specific to thymocyte development. Immunodeficiency can be profound.[8] Loss of the thymus at an early age through genetic mutation (as in DiGeorge syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, or a vary rare "nude" thymus causing absence of hair and the thymus[14]) results in severe immunodeficiency and subsequent high susceptibility to infection by viruses, protozoa, and fungi.[15] Nude mice with the very rare "nude" deficiency as a result of FOXN1 mutation are a strain of research mice as a model of T cell deficiency.[16]

The most common congenital cause of thymus-related immune deficiency results from the deletion of the 22nd chromosome, called DiGeorge syndrome.[14][15] This results in a failure of development of the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches, resulting in failure of development of the thymus, and variable other associated problems, such as congenital heart disease, and abnormalities of mouth (such as cleft palate and cleft lip), failure of development of the parathyroid glands, and the presence of a fistula between the trachea and the oesophagus.[15] Very low numbers of circulating T cells are seen.[15] The condition is diagnosed by fluorescent in situ hybridization and treated with thymus transplantation.[14]

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) are group of rare congenital genetic diseases that can result in combined T, B, and NK cell deficiencies.[15] These syndromes are caused by mutations that affect the maturation of the hematopoietic progenitor cells, which are the precursors of both B and T cells.[15] A number of genetic defects can cause SCID, including IL-2 receptor gene loss of function, and mutation resulting in deficiency of the enzyme adenine deaminase.[15]

Autoimmune disease

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1, is a rare genetic autoimmune syndrome that results from a genetic defect of the thymus tissues.[17] Specifically, the disease results from defects in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene, which stimulates expression of self antigens in the epithelial cells within the medulla of the thymus. Because of defects in this condition, self antigens are not expressed, resulting in T cells that are not conditioned to tolerate tissues of the body, and may treat them as foreign, stimulating an immune response and resulting in autoimmunity.[17] People with APECED develop an autoimmune disease that affects multiple endocrine tissues, with the commonly affected organs being hypothyroidism of the thyroid gland, Addison's disease of the adrenal glands, and candida infection of body surfaces including the inner lining of the mouth and of the nails due to dysfunction of TH17 cells, and symptoms often beginning in childhood. Many other autoimmune diseases may also occur.[17] Treatment is directed at the affected organs.[17]

Thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity

Thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity can occur in people with thymoma. In this condition, the T cells developed in the thymus are directed against the tissues of the body. This is because the malignant thymus is incapable of appropriately educating developing thymocytes to eliminate self-reactive T cells. The condition is virtually indistinguishable from graft versus host disease.[18]

Myasthenia gravis

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease most often due to antibodies that block acetylcholine receptors, involved in signalling between nerves and muscles.[19] It is often associated with thymic hyperplasia or thymoma,[19] with antibodies produced probably because of T cells that develop abnormally.[20] Myasthenia gravis most often develops between young and middle age, causing easy fatiguing of muscle movements.[19] Investigations include demonstrating antibodies (such as against acetylcholine receptors or muscle-specific kinase), and CT scan to detect thymoma or thymectomy.[19] With regard to the thymus, removal of the thymus, called thymectomy may be considered as a treatment, particularly if a thymoma is found.[19] Other treatments include increasing the duration of acetylcholine action at nerve synapses by decreasing the rate of breakdown. This is done by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as pyridostigmine.[19]

Cancer

Thymomas

Tumours originating from the thymic epithelial cells are called thymomas.[3] They most often occur in adults older than 40.[3] Tumours are generally detected when they cause symptoms, such as a neck mass or affecting nearby structures such as the superior vena cava;[20] detected because of screening in patients with myasthenia gravis, which has a strong association with thymomas and hyperplasia;[3] and detected as an incidental finding on imaging such as chest x-rays.[20] Hyperplasia and tumours originating form the thymus are associated with other autoimmune diseases - such as hypogammaglobulinemia, Graves disease, pure red cell aplasia, pernicious anaemia and dermatomyositis, likely because of defects in negative selection in proliferating T cells.[3][21]

Thymomas can be benign; benign but by virtue of expansion, invading beyond the capsule of the thymus ("invasive thyoma"), or malignant (a carcinoma).[3] This classification is based on the appearance of the cells.[3] A WHO classification also exists but is not used as part of standard clinical practice.[3] Benign tumours confined to the thymus are most common; followed by locally invasive tumours, and then by carcinomas.[3] There is variation in reporting, with some sources reporting malignant tumours as more common.[21] Invasive tumours, although not technically malignant, can still spread (metastasise) to other areas of the body.[3] Even though thymomas occur of epithelial cells, they can also contain thymocytes.[3] Treatment of thymomas often requires surgery to remove the entire thymus.[21] This may also result in temporary remission of any associated autoimmune conditions.[21]

Lymphomas

Tumours originating from T cells of the thymus form a subset of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL).[22] These are similar in symptoms, investigation approach and management to other forms of ALL.[22] Symptoms that develop, like other forms of ALL, relate to deficiency of platelets, resulting in bruising or bleeding; immunosuppression resulting in infections; or infltration by cells into parts of the body, resulting in an enlarged liver, spleen, lymph nodes or other sites.[22] Blood test might reveal a large amount of white blood cells or lymphoblasts, and deficiency in other cell lines - such as low platelets or anaemia.[22] Immunophenotyping will reveal cells that are CD3, a protein found on T cells, and help further distinguish the maturity of the T cells. Genetic analysis including karyotyping may reveal specific abnormalities that may influence prognosis or treatment, such as the Philadelphia translocation.[22] Management can include multiple courses of chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, and management of associated problems, such as treatment of infections with antibiotics, and blood transfusions. Very high white cell counts may also require cytoreduction with apheresis.[22]

Tumours originating from the small population of B cells present in the thymus lead to primary mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphomas.[23] These are a rare subtype of Non-Hodgkins lymphoma, although by the activity of genes and occasionally microscopic shape, unusually they also have the characteristics of Hodgkins lymphomas.[24] that occur most commonly in young and middle-aged, more prominent in females.[24] Most often, when symptoms occur it is because of compression of structures near the thymus, such as the superior vena cava or the upper respiratory tract; when lymph nodes are affected it is often in the mediastinum and neck groups.[24] Such tumours are often detected with a biopsy that is subject to immunohistochemistry. This will show the presence of clusters of differentiation, cell surface proteins - namely CD30, with CD19, CD20 and CD22, and with the absence of CD15. Other markers may also be used to confirm the diagnosis.[24] Treatment usually includes the typical regimens of CHOP or EPOCH or other regimens; regimens generally including cyclophosphamide, an anthracycline, prednisone, and other chemotherapeutics; and potentially also a stem cell transplant.[24]

Thymic cysts

The thymus may contain cysts, usually less than 4 cm in diameter. Thymic cysts are usually detected incidentally and do not generally cause symptoms.[3] Thymic cysts can occur along the neck or in the chest (mediastinum).[25] Cysts usually just contain fluid and are lined by either many layers of flat cells or column-shaped cells.[25] Despite this, the presence of a cyst can cause problems similar to those of thymomas, by compressing nearby structures,[3] and some may contact internal walls (septa) and be difficult to distinguish from tumours.[25] When cysts are found, investigation may include a workup for tumours, which may include CT or MRI scan of the area the cyst is suspected to be in.[3][25]

Surgical removal

Thymectomy is the surgical removal of the thymus.[2] The usual reason for removal is to gain access to the heart for surgery to correct congenital heart defects in the neonatal period.[26] Other indications for thymectomy include the removal of thymomas and the treatment of myasthenia gravis.[2] In neonates the relative size of the thymus obstructs surgical access to the heart and its surrounding vessels.[26] Removal of the thymus in infancy results in often fatal immunodeficiency, because functional T cells have not developed.[2] In older children and adults, which have a functioning lymphatic system with mature T cells also situated in other lymphoid organs, the effect is lesser, and limited to failure to mount immune responses against new antigens.[2]

Society and culture

When used as food for humans, the thymus of animals is known as one of the kinds of sweetbread.[27]

History

The thymus was known to the ancient Greeks, and its name comes from the Greek word θυμός (thumos), meaning "anger", or "heart, soul, desire, life", possibly because of its location in the chest, near where emotions are subjectively felt;[28] or else the name comes from the herb thyme (also in Greek θύμος or θυμάρι), which became the name for a "warty excrescence", possibly due to its resemblance to a bunch of thyme.[29]

Galen was the first to note that the size of the organ changed over the duration of a person's life.[30]

In the nineteenth century, a condition was identified as status thymicolymphaticus defined by an increase in lymphoid tissue and an enlarged thymus. It was thought to be a cause of sudden infant death syndrome but is now an obsolete term.[31]

The importance of the thymus in the immune system was discovered in 1961 by Jacques Miller, by surgically removing the thymus from one day old mice, and observing the subsequent deficiency in a lymphocyte population, subsequently named T cells after the organ of their origin.[32][33] Until the discovery of its immunological role, the thymus had been dismissed as a "evolutionary accident", without functional importance.[13] The role the thymus played in ensuring mature T cells tolerated the tissues of the body was uncovered in 1962, with the finding that T cells of a transplanted thymus in mice demonstrated tolerance towards tissues of the donor mouse.[13] B cells and T cells were identified as different types of lymphocytes in 1968, and the fact that T cells required maturation in the thymus was understood.[13] The subtypes of T cells (CD8 and CD4) were identified by 1975.[13] The way that these subclasses of T cells matured - positive selection of cells that functionally bound to MHC receptors - was known by the 1990s.[13] The important role of the AIRE gene, and the role of negative selection in preventing autoreactive T cells from maturing, was understood by 1994.[13]

Recently, advances in immunology have allowed the function of the thymus in T-cell maturation to be more fully understood.[13]

Other animals

The thymus is present in all jawed vertebrates, where it undergoes the same shrinkage with age and plays the same immunological function as in other vertebrates. Recently, a discrete thymus-like lympho-epithelial structure, termed the thymoid, was discovered in the gills of larval lampreys.[34] Hagfish possess a protothymus associated with the pharyngeal velar muscles, which is responsible for a variety of immune responses.[35]

The thymus is also present in most other vertebrates with similar structure and function as the human thymus. A second thymus in the neck has been reported sometimes to occur in the mouse[36] As in humans, the guinea pig's thymus naturally atrophies as the animal reaches adulthood,[37] but the athymic hairless guinea pig (which arose from a spontaneous laboratory mutation) possesses no thymic tissue whatsoever, and the organ cavity is replaced with cystic spaces.[38]

Additional images

- Thymus of a fetus

On chest X-ray, the thymus appears as a radiodense (brighter in this image) mass by the upper lobe of the child's right (left in image) lung.

On chest X-ray, the thymus appears as a radiodense (brighter in this image) mass by the upper lobe of the child's right (left in image) lung.

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1273 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Standring S, et al., eds. (2008). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- Standring S, Gray H, eds. (2016). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 983–6. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC (2014-08-27). "Chapter 13. Diseases of White Blood Cells, Lymph Nodes, Spleen, and Thymus: Thymus.". Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th (online) ed.). ISBN 9780323296397.

- Young B, O'Dowd G, Woodford P (2013). Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 204–6. ISBN 9780702047473.

- Larsen W (2001). Human Embryology (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 366–367. ISBN 978-0-443-06583-5.

- Swiss embryology (from UL, UB, and UF) qblood/lymphat03

- Venturi S, Venturi M (September 2009). "Iodine, thymus, and immunity". Nutrition. 25 (9): 977–9. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2009.06.002. PMID 19647627.

- Davidson's 2018, p. 67.

- Sutherland JS, Goldberg GL, Hammett MV, Uldrich AP, Berzins SP, Heng TS, et al. (August 2005). "Activation of thymic regeneration in mice and humans following androgen blockade". Journal of Immunology. 175 (4): 2741–53. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2741. PMID 16081852.

- Hall JE (2016). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (13th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 466–7. ISBN 978-1-4557-7016-8.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC (2014-08-27). "Chapter 6. Diseases of the immune system. The normal immune system.". Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th (online) ed.). ISBN 9780323296397.

- Hohl TM (2019). "6. Cell mediated defence against infection: Thymic selection of CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells". In Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ (eds.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (9th (online) ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 9780323482554.

- Miller JF (May 2011). "The golden anniversary of the thymus". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 11 (7): 489–95. doi:10.1038/nri2993. PMID 21617694.

- Harrison's 2015, pp. 2493.

- Davidson's 2018, pp. 79-80.

- Fox JG (2006). The Mouse in Biomedical Research: Immunology. Elsevier. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-08-046908-9.

- Harrison's 2015, pp. 2756-7.

- Wadhera A, Maverakis E, Mitsiades N, Lara PN, Fung MA, Lynch PJ (October 2007). "Thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity: a graft-versus-host-like disease". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 57 (4): 683–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.027. PMID 17433850.

- Davidson's 2018, pp. 1141-43.

- Engels EA (October 2010). "Epidemiology of thymoma and associated malignancies". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 5 (10 Suppl 4): S260-5. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f1f62d. PMC 2951303. PMID 20859116.

- Harrison's 2015, pp. 2759.

- Larson RA (2015). "Chapter 91: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Williams hematology (online) (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0071833004.

- Dabrowska-Iwanicka A, Walewski JA (September 2014). "Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma". Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports. 9 (3): 273–83. doi:10.1007/s11899-014-0219-0. PMC 4180024. PMID 24952250.

- Smith SD, Press OW (2015). "Chapter 98. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma and Related Diseases". Williams hematology (online) (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0071833004.

- Goldstein, Alan J.; Oliva, Isabel; Honarpisheh, Hedieh; Rubinowitz, Ami (1 February 2015). "A Tour of the Thymus: A Review of Thymic Lesions with Radiologic and Pathologic Correlation". Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal. 66 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1016/j.carj.2013.09.003.

- Eysteinsdottir JH, Freysdottir J, Haraldsson A, Stefansdottir J, Skaftadottir I, Helgason H, Ogmundsdottir HM (May 2004). "The influence of partial or total thymectomy during open heart surgery in infants on the immune function later in life". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 136 (2): 349–55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02437.x. PMC 1809033. PMID 15086401.

- "Sweetbread recipes - BBC Food". BBC Food. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- Liddell HG, Scott R. "θυμός". A Greek-English Lexicon. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- "thymus | Origin and meaning of thymus by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- Nishino M, Ashiku SK, Kocher ON, Thurer RL, Boiselle PM, Hatabu H (2006). "The thymus: a comprehensive review". Radiographics. 26 (2): 335–48. doi:10.1148/rg.262045213. PMID 16549602.

- Sapolsky RM (2004). Why zebras don't get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York: Henry Hold and Co./Owl Books. pp. 182–185. ISBN 978-0805073690.

- Miller JF (July 2002). "The discovery of thymus function and of thymus-derived lymphocytes". Immunological Reviews. 185 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.18502.x. PMID 12190917.

- Miller JF (June 2004). "Events that led to the discovery of T-cell development and function--a personal recollection". Tissue Antigens. 63 (6): 509–17. doi:10.1111/j.0001-2815.2004.00255.x. PMID 15140026.

- Bajoghli B, Guo P, Aghaallaei N, Hirano M, Strohmeier C, McCurley N, et al. (February 2011). "A thymus candidate in lampreys". Nature. 470 (7332): 90–4. Bibcode:2011Natur.470...90B. doi:10.1038/nature09655. PMID 21293377.

- Riviere HB, Cooper EL, Reddy AL, Hildemann WH (1975). "In Search of the Hagfish Thymus" (PDF). American Zoologist. 15 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1093/icb/15.1.39. JSTOR 3882269.

- Terszowski G, Müller SM, Bleul CC, Blum C, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J, et al. (April 2006). "Evidence for a functional second thymus in mice". Science. 312 (5771): 284–7. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..284T. doi:10.1126/science.1123497. PMID 16513945.

- Suckow, Mark A.; Stevens, Karla A.; Wilson, Ronald P. (2012). The Laboratory Rabbit, Guinea Pig, Hamster, and Other Rodents. Academic Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-12-380920-9.

- Gershwin, M. Eric; Merchant, Bruce (2012). Immunologic Defects in Laboratory Animals 1. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-4757-0325-2.

- Books

- Ralston SH, Penman ID, Strachan MW, Hobson RP, eds. (2018). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

- Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J (2015). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (19th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 9780071802154.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thymus (organ). |

- T cell development in the thymus. Video by Janice Yau, describing stromal signaling and tolerance. Department of Immunology and Biomedical Communications, University of Toronto. Masters Research Project, Master of Science in Biomedical Communications. 2011.