Bewick's wren

The Bewick's wren (Thryomanes bewickii) is a wren native to North America. At about 14 cm (5.5 in) long, it is grey-brown above, white below, with a long white eyebrow. While similar in appearance to the Carolina wren, it has a long tail that is tipped in white. The song is loud and melodious, much like the song of other wrens. It lives in thickets, brush piles and hedgerows, open woodlands and scrubby areas, often near streams. It eats insects and spiders, which it gleans from vegetation or finds on the ground.[2]

| Bewick's wren | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Troglodytidae |

| Genus: | Thryomanes P.L. Sclater, 1862 |

| Species: | T. bewickii |

| Binomial name | |

| Thryomanes bewickii (Audubon, 1829) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

1–2 dozen living, 2 recently extinct; see article text | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

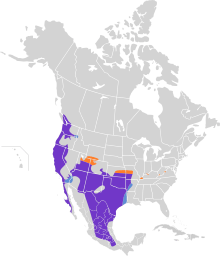

Its historic range was from southern British Columbia, Nebraska, southern Ontario, and southwestern Pennsylvania, Maryland, south to Mexico, Arkansas and the northern Gulf States. However, it is now extremely rare east of the Mississippi River.[3]

Taxonomy

John James Audubon is credited with having first described a specimen of the Bewick's wren, collecting the first known specimen in 1821. The Bewick's Wren is named after Audubon's friend Thomas Bewick, an English engraver and natural historian.[3]

This is currently the only species of its genus, Thryomanes. The Socorro wren, formerly placed here too, is actually a close relative of the house wren complex, as indicated by biogeography and mtDNA NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 sequence analysis, whereas Thryomanes seems not too distant from the Carolina wren.[4]

Subspecies

A list of commonly recognized subspecies follows. Two have gone extinct during the 20th century, mainly due to habitat destruction and cat predation.[5]

- T. b. bewickii – (Audubon, 1827): nominate, Midwestern USA from NE Kansas to Missouri and E Texas. Includes T. b. pulichi as a junior synonym.

- T. b. altus – Aldrich, 1944: Formerly in Appalachian region; S Ontario to South Carolina, now quite rare. Possibly an endangered subspecies, but possibly not distinct from bewickii.

- T. b. cryptus – Oberholser, 1898: Central Kansas to N Tamaulipas in Mexico. Includes T. b. niceae. Southeastern birds are sometimes separated as T. b. sadai.

- T. b. eremophilus – Oberholser, 1898: E California inland, south to Zacatecas in Mexico.

- T. b. calophonus – Oberholser, 1898: SW British Columbia, Canada, to W Oregon. Includes T. b. ariborius and T. b. hurleyi. The former name refers to the population found in the area of Seattle and Vancouver; these birds are sometimes called Seattle wren.

- T. b. marinensis – Grinnell, 1910: Coastal NW California to Marin County.

- T. b. spilurus – (Vigors, 1839): Coastal California from San Francisco Bay to Santa Cruz County.

- T. b. drymoecus – Oberholser, 1898: SW Oregon to California Central Valley.

- T. b. atrestus – Oberholser, 1932: S Oregon to W Nevada. Probably not valid.

- T. b. correctus Grinnell. SW coastal California to Mexican border; possibly synonym of charienturus.

- T. b. charienturus – Oberholser, 1898: N Baja California Peninsula to about 30°N.

- T. b. magdalenensis – Huey, 1942: SW Baja California Peninsula from 26 to 24°N.

- T. b. nesophilus Oberholser. Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Anacapa Islands, California; probably also Santa Barbara and San Nicolas; found on the mainland in winter. Possibly synonym of charienturus.

- T. b. catalinae – Grinnell: Santa Catalina Island, California; found on the mainland in winter. Possibly synonym of charienturus.

- T. b. cerroensis – (Anthony, 1897): Cedros Island (Mexico) and W central Baja California. Includes T. b. atricauda.

- T. b. leucophrys † – (Anthony, 1895): San Clemente Bewick's wren. Formerly San Clemente Island, California.

- Extinct since the 1940s due to habitat destruction by feral goats and sheep. Also called T. b. anthonyi. Observations of leucophrys in 1897[6] refer to cerroensis; at that time, the San Clemente wren was considered a good species which included the Cedros population.

- T. b. brevicauda † – Ridgway, 1876: Guadalupe Bewick's wren. Formerly Guadalupe Island, Mexico.

- This subspecies is extinct since (probably) the late 1890s due to habitat destruction by feral goats and predation by feral cats. Overcollecting by scientists might have hastened its demise.[7] It was last collected (3 specimens) by Anthony and Streator in May 1892[7] and seen but found to be "nearly extinct" on March 22, 1897.[6] It was not found by Anthony in several searches between 1892 and 1901 and considered certainly extinct by 1901;[7] a thorough search in 1906 confirmed the subspecies' extinction.[8][9]

- T. b. murinus – (Hartlaub, 1852): Eastern and central Mexico.

- T. b. bairdi – (Salvin and Goodman): SE Mexico to S Puebla.

- T. b. percnus – (Oberholser): Jalisco to Guerrero, Mexico.

The last three are sometimes united as T. b. mexicanus. The validity of subspecies needs to be verified using freshly caught birds and/or molecular data, as specimens are prone to foxing quickly.[5]

Description

The Bewick's wren has an average length of 5.1 inches (13 cm) and an average weight of 0.3 to 0.4 ounces (8 -12 g). Its plumage is brown on top and light grey underneath, with a white stripe above each eye. Its beak is long, slender, and slightly curved.[2] Its most distinctive feature is its long tail with black bars and white corners. It moves its tail around frequently, making this feature even more obvious for observers.[10]

Juveniles look similar to adults, with only a few key differences. Their beaks are usually shorter and stockier. In addition, their underbelly might feature some faint speckling.[2] Males and females are very similar in appearance.[2]

Vocalizations

Bewick's wrens, like many wrens, are very vocal. Both females and males make short calls while foraging and both use a harsh scolding call when agitated.[2] Males also sing in order to attract mates and protect their territory.[2] The song is broken into two or three individual parts; one individual male may exhibit up to twenty-two different variations on the song pattern, and may even throw in a little ventriloquism to vary it even further.[11] A male wren learns its song from neighboring males, so its song will be different from its father's.[2]

Geographic variation

Geographic differences have been observed in the appearance of the Bewick's wren. Eastern populations, prior to their decline, were described as being more colorful, such as having a reddish tint to its brown feathers. Pacific populations are described as being darker in appearance, while populations in the Southwest are described as having a grayer plumage.[10]

Geographic differences have also been noted in the song of Bewick's wrens. Each regional population of Bewick's wrens have distinctive vocalizations, in particular their call notes. Pacific populations sing notably more complicated songs than Southwestern populations. Eastern populations were also noted to be excellent singers.[10]

Distribution and habitat

The Bewick's wren once had a range that extended throughout much of the United States and Mexico and parts of Canada. It used to be fairly common in the Midwest and in the Appalachian Mountains, but it is now extremely rare east of the Mississippi River. It is still found along the Pacific Coast from Baja California to British Columbia, in Mexico, and in a significant portion of the Southwest, including Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.[3] Western populations do not tend to migrate. Eastern populations, prior to their decline, used to migrate from its northern range to the Gulf Coast.[2]

The preferred habitat of the Bewick's wren is that of open woodlands and brush-filled areas such as hillsides and uplands. They are more common than house wrens in drier habitats, such as those found in the Southwest.[3] In California, Bewick's wrens inhabit a shrubland area called chaparral.[12]

Behavior

Feeding

Bewick's wrens are insect eaters. They glean insects and insect eggs from vegetation, including the trunks of trees. They typically do not feed on vegetation higher than 3 meters, but they will forage on the ground.[3] Bewick's wrens are capable of hanging upside down in order to acquire food, such as catching an insect on the underside of a branch. When it catches an insect, it kills the insect prior to swallowing it whole. Bewick's wrens will repeatedly wipe their beaks on its perch after a meal.

Bewick's wrens will visit backyard feeders. They will eat suet, peanut hearts, hulled sunflower seeds, and mealworms.[13] Like many insect-eating birds, the Bewick's wren widens its diet to include seeds in the winter.[14]

Breeding

Courtship begins with the male singing from its perch. It will occasionally pause its song in order to chase its competitors. Bewick's wrens form monogamous pairs that will then forage together.[2] The male wren begins building the nest in a cavity or birdhouse, with the female joining in later. The nest is constructed from twigs and other plant materials and is often lined with feathers. The nest is cup-shaped and located in a nook or cavity of some kind. It lays 5–7 eggs that are white with brown spots. The Bewick's wren produces two broods in a season. Pairs are more or less monogamous when it comes to breeding, but go solitary throughout the winter.[5]

Status and conservation

In 2016, the Bewick's wren was listed as least concern on the IUCN Red List of threatened species due to the size of its range and estimates of its population size.[15] However, ornithologists have noted a severe decline in its eastern range and parts of its western range.[3] In particular, it has virtually disappeared from east of the Mississippi. In 1984, the state of Maryland classified the Bewick's wren as endangered under its Maryland Endangered Species Act of 1971. Despite this classification, no breeding pairs of Bewick's wrens are known to remain in Maryland.[16] In 2014, the North American Bird Conservation Initiative placed the eastern Bewick's wren on its watch list.[17]

Several theories have been proposed to explain its decline in its eastern range, including pesticide use and competition from other bird species.[3] The most likely reason seems to be competition from house wrens. House wrens compete with Bewick's wrens for similar nesting sites. House wrens will destroy both the nests and eggs of Bewick's wrens.[2] The reforestation of once open land has also negatively impacted the eastern Bewick's wrens.[2]

In California, habitat loss due to development has impacted the Bewick's wren. In San Diego, the development of canyons has led to the gradual decline of native bird species, including the Bewick's wren.[12]

In Washington, development has actually benefited the Bewick's wren, leading to an increase in its population. However, this has coincided with the decline of the Pacific wren thanks to increased competition between the two species.[18]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Thryomanes bewickii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Bewick's Wren". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- "Bewick's Wren - Introduction | Birds of North America Online". birdsna.org. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- Martínez Gómez; Juan E.; Barber, Bruian R. & Peterson, A. Townsend (2005). "Phylogenetic position and generic placement of the Socorro Wren (Thryomanes sissonii)" (PDF). Auk. 122 (1): 50–56. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[0050:PPAGPO]2.0.CO;2. hdl:1808/16612. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- Kennedy, E.D.; White, D.W. (1997). Poole, A.; Gill, F. (eds.). "Bewick's Wren (Thryomanes bewickii)". The Birds of North America. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA & The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, D.C. (315). doi:10.2173/bna.315.

- Kaeding, Henry B. (1905). "Birds from the West Coast of Lower California and Adjacent Islands (Part II)" (PDF). Condor. 7 (4): 134–138. doi:10.2307/1361667. JSTOR 1361667.

- Anthony, A.W. (1901). "The Guadalupe Wren" (PDF). Condor. 3 (3): 73. doi:10.2307/1361475. JSTOR 1361475.

- Thayer, John E.; Bangs, Outram (1908). "The Present State of the Ornis of Guadaloupe Island" (PDF). Condor. 10 (3): 101–106. doi:10.2307/1360977. hdl:2027/hvd.32044072250186. JSTOR 1360977.

- The often-reported extinction date of 1903 seems to be the first record of its absence rather than the last record of its presence. Actually, there appears to be no post-1897 record. The schedule of Anthony's visits after 1892 is not known; if he visited the island before 1897 he must have overlooked the last remnant of the population and thus his extinction date of 1901 may be called into question. By the balance of evidence, it is likely however that the subspecies became extinct between 1897 and 1901.

- Kaufman, Kenn (2006). "Bewick's Wren". Birder's World. 20: 60–61.

- Beedy, Edward C.; Pandolfino, Edward R. (2013-06-17). Birds of the Sierra Nevada: Their Natural History, Status, and Distribution. ISBN 9780520274938.

- Diamond, Jared (1988). "Urban extinction of birds". Nature. 333 (6172): 393–394. Bibcode:1988Natur.333..393D. doi:10.1038/333393a0.

- "Common Feeder Birds - FeederWatch". feederwatch.org. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- "Winter - Wild Birds Unlimited". Wild Birds Unlimited. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- "Thryomanes bewickii (Bewick's Wren)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- "Wrens of Maryland - Maryland's Wild Acres". dnr2.maryland.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- "2014 Report — The State of the Birds Report 2014". www.stateofthebirds.org. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- Farwell, Laura; Marzluff, John (2013). "A new bully on the block: Does urbanization promote Bewick's wren (Thryomanes bewickii) aggressive exclusion of Pacific wrens (Troglodytes pacificus)?". Biological Conservation. 161: 128–141. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.03.017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thryomanes bewickii. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Thryomanes bewickii |

- Bewick's wren - Thryomanes bewickii - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Bewick's wren Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "Bewick's wren media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Bewick's wren photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Thryomanes bewickii at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Bewick's wren on Xeno-canto.