Heracleion

Heracleion (Ancient Greek: Ἡράκλειον), also known by its Egyptian name Thonis (Ancient Egyptian: Tȝ-ḥn.t, Coptic: ⲧϩⲱⲛⲓ, Ancient Greek: Θῶνις)[1] and sometimes called Thonis-Heracleion, was an ancient Egyptian city located near the Canopic Mouth of the Nile, about 32 km (20 miles) northeast of Alexandria. Its ruins are located in Abu Qir Bay, currently 2.5 km off the coast, under 10 m (30 ft) of water.[2] A stele found on the site indicates that it was one single city known by both its Egyptian and Greek names.[3] Its legendary beginnings go back to as early as the 12th century BC, and it is mentioned by ancient Greek historians. Its importance grew particularly during the waning days of the Pharaohs.[4]

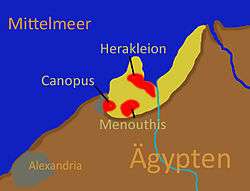

Map of Nile Delta showing ancient Canopus, Heracleion, and Menouthis | |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Location | near Alexandria, Egypt |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°18′15″N 30°06′02″E |

Legendary beginnings

Heracleion is mentioned by many chroniclers in antiquity, including Herodotus, Strabo and Diodorus.[3] The city was said by Herodotus to have been visited by Paris and Helen of Troy[5] before the Trojan war began.[6] They sought refuge there on their flight from the jealous Menelaus,[3] but were rebuffed by Thonis, the watchman at the entrance to the Nile.[7] Alternatively it was believed that Menelaus and Helen had stayed there, accommodated by the noble Egyptian Thon[8] and his wife Polydamna. The 2nd century BC Greek poet Nicander wrote that Menelaus’s helmsman, Canopus, was bitten by a viper on the sands of Thonis.[4] According to Herodotus, a great temple was built at the spot where Heracles first arrived in Egypt.[6] The story of Heracles' visit resulted in the Greeks calling the city by the Greek name Heracleion rather than its original Egyptian name Thonis.

History

Heracleion was originally built on some adjoining islands in the Nile Delta. It was intersected by canals[4] with a number of harbors and anchorages. Its wharves, temples and tower-houses were linked by ferries, bridges, and pontoons. The city was an emporion (trading port)[3] and in the Late Period of ancient Egypt it was the country's main port for international trade[4] and collection of taxes. It had a sister city, Naucratis, which was another trading port lying 72 km (45 mi) further up the Nile. Goods were transferred inland via Naucratis, or they were transported via the Western Lake and through a water channel to the nearby town of Canopus for onward distribution.[3]

Heracleion had a large temple of Khonsou, son of Amun, who was known to the Greeks as Herakles.[9] Later, the worship of Amun became more prominent. During the time when the city especially flourished between the 6th and 4th centuries BC, a large temple of Amun-Gereb, the supreme god of the Egyptians at the time, was located in the middle of the city.[10] Pharaoh Nectanebo I made many additions to the temple in the 4th century B.C.[3] Sanctuaries in Heracleion dedicated to Osiris and other gods were famous for miraculous healing and attracted pilgrims from a wide area.[4] The city was the site of the celebration of the "Mysteries of Osiris" each year during the month of Khoiak. The god in his ceremonial boat was brought in procession from the temple of Amun in that city to his shrine in Canopus.

During the 2nd century BC Alexandria superseded Heracleion as Egypt’s primary port. Over time the city was weakened by a combination of earthquakes, tsunamis and rising sea levels. At the end of the 2nd century BC, probably after a severe flood, the ground on which central island of Heracleion was built succumbed to soil liquefaction. The hard clay turned rapidly into a liquid and the buildings collapsed into the water. A few residents stayed on during the Roman era and the beginning of Arab rule, but by the end of the eighth century AD what was left of the city had sunk beneath the sea.[3]

Ancient references

Until very recently the site had been known only from a few literary and epigraphic sources, one of which interestingly mentions the site as an emporion, just like Naukratis.

The city was mentioned by the ancient historians Diodorus (1.19.4) and Strabo (17.1.16). Herodotus was told that Thonis was the warden of the Canopic mouth of the Nile: Thonis arrested Alexander (Paris), the son of Priam, because Alexander had abducted Helen of Troy and taken much wealth.[11][12]

Heracleion is also mentioned in the twin steles of the Decree of Nectanebo I (the first of which is known as the 'Stele of Naukratis'), which specify that one tenth of the taxes on imports passing through the town of Thonis/Herakleion were to be given to the sanctuary of Neith of Sais.[11] The city is also mentioned in the Decree of Canopus honoring Pharaoh Ptolemy III, which describes donations, sacrifices and a procession on water.[4]

Archaeology

In 1933, an RAF commander flying over Abu Qir Bay saw ruins under the water. At that time, most historians believed that Thonis and Heracleion were two separate cities, both located on what is now the Egyptian mainland.[3] The ruins submerged in the sea were located and explored by the French underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio in 1999, after a five-year search.[13] Numerous finds from the site have indicated that the city's period of major activity ran from the 6th to the 4th century BC,[10] with finds of pottery and coins appearing to stop at the end of the 2nd century BC.[3] Goddio's finds have also included incomplete statues of the god Serapis and the queen Arsinoe II.[14] No more than 5% of the city's area was explored by the archaeologist.[3]

Around 2010 a baris, a type of ancient Nile river boat, was excavated from the waters around Heracleion.[15] Its design was found to be consistent with a description written by Herodotus in 450 BC.[16] In July 2019, a small Greek temple, ancient granite columns, treasure-carrying ships, and bronze coins from the reign of Ptolemy II, dating back to the third and fourth centuries BC, were found at Heracleion. The investigations were conducted by Egyptian and European divers led by Goddio. They also uncovered a devastated historic temple (the city’s main temple) underwater off Egypt's north coast.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

See also

References

- "TM Places". www.trismegistos.org. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- "Heracleion Photos: Lost Egyptian City Revealed After 1,200 Years Under Sea". The Huffington Post. 29 April 2013.

- Shenker, Jack (15 Aug 2016). "Lost cities #6: how Thonis-Heracleion resurfaced after 1,000 years under water". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 Feb 2018.

- Dalya Alberge (2 August 2015). "Ancient Egyptian underwater treasures to be exhibited for the first time". The Guardian.

- Little, Reg (26 February 2015). "Oxford University and the rediscovery of the lost Egyptian city of Heracleion". The Northern Echo.

- "Sunken Civilizations". Franck Goddio. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Hammond, Andrew (2017). Pop Culture in North Africa and the Middle East. Entertainment and Society around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 217. ISBN 9781440833847.

- Stephanus of Byzantium. "Θῶνις". Ethnika kat' epitomen (in Greek).

- Anne Burton, Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. BRILL, 1972 ISBN 9004035141 p105

- "Lost city of Heracleion gives up its secrets". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- Naukratis: a city and trading port in Egypt, British Museum

- Herodotus, Histories, 2.113-115

- "You won't believe what they found under the sea!". Geeks VIP. 12 July 2015. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018.

- Sooke, Alastair. "Sunken Cities: the man who found Atlantis". The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- Alexander Belov (2014). "A New Type of Construction Evidenced by Ship 17 of Thonis-Heracleion" (PDF). The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. Moscow: Center for Egyptological Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12060.

- Dalya Alberge (17 March 2019). "Nile shipwreck discovery proves Herodotus right – after 2,469 years". The Guardian.

- "Mysterious temple discovered in the ruins of sunken ancient city". 9news.com. 26 July 2019.

- History, Laura Geggel 2019-07-29T10:37:58Z. "Divers Find Remains of Ancient Temple in Sunken Egyptian City". livescience.com. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- cowie, ashley. "Subaquatic Temple and Countless Treasures Discovered in Egypt's Sunken City of Heracleion". www.ancient-origins.net. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Santos, Edwin (2019-07-28). "Archaeologists discover a sunken ancient settlement underwater". Nosy Media. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- EDT, Katherine Hignett On 7/23/19 at 11:06 AM (2019-07-23). "Ancient Egypt: Underwater archaeologists uncover destroyed temple in the sunken city of Heracleion". Newsweek. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Topics, Head. "Archaeologists discover a sunken ancient settlement underwater". Head Topics. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heracleion (Thonis). |

- Franck Goddio official website

- "Spectacular finds of lost city revealed". News. BBC. 7 June 2001. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- "Searching for Sunken Cities". Ancient Egypt Magazine. Jul–Aug 2000.

- "Sunken Egyptian city reveals 1,200-year-old secrets". Yahoo!. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- Photos of underwater treasures of Heracleion (French text)