Thomas Williams (pioneer)

Thomas Williams (died November 30, 1785), originally from Albany, New York, settled in Detroit, Michigan in 1765.[lower-alpha 1] He married Cecile Chapeau from a prominent French-Canadian family that had settled in Michigan in 1710. Williams was a merchant, landowner, and was active in civic and political affairs. Goods were transported to Detroit from Albany via canoe, which could take a number of months for a round-trip. He petitioned for equitable opportunities to engage in trade at Fort Niagara and Detroit. In his role as justice of the peace, he was charged to uphold the law and punish those who were deemed to have broken the law. As notary, he executed legal documents for the settlement. He was also town crier and took the 1782 census. He married Cecile Campeau from a prominent family of French heritage who had come to Michigan about 1710. Cecile's brother, Joseph, was the state's first millionaire. Their son, John R. Williams, was the first mayor of Detroit.

Early life

Williams was born in Albany, New York,[1] where his ancestors settled in 1690.[2] He served in the New York militia as an officer.[3] Williams settled in Detroit in 1765.[2][lower-alpha 1]

Career

Williams was a trader and licensed merchant,[6] who brought goods to Detroit from Albany via canoe.[3] The round-trip could many months.[6] In 1768, he made the round-trip with George Meldrum from Schenectady.[3] His partner was John Casety.[7]

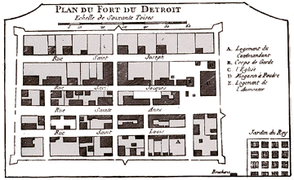

Williams signed a number of petitions against British regulation to sell goods at posts. The political climate was difficult between the British, who had taken rule of Detroit in 1760 and the French, with whom they were still at war in 1762. The French and the Indians attacked the British in May 1763 in what was called the Siege of Fort Detroit. Traders coming to Fort Detroit were killed or captured.[8] Civil unrest continued, particularly regarding the restriction of trading to the posts by the British and a monopoly that William Rutherford held at Fort Niagara. Williams signed a number of petitions against the regulations in 1766 and 1767. In 1766, he was one of the merchants allowed to trade at Fort Niagara.[5] Indians, on their way to Fort Niagara, were often met by people on the lake who sold them their wares, which drove down business at the fort.[9] The British rules also favored the French who were given the fur trade, allowed to winter with the Indians and trade in the process, and got around rules for trading rum by selling on credit.[10] Many of the traders in the region that signed the petitions were from Albany, many of the Albany Dutch.[9]

He was also active in civic and political affairs.[11] Captn. Richard B. Lernhout, the military commandant, appointed Thomas justice of the peace and notary[12] and/or judge in Detroit under British rule.[13] As justice of the peace, his duties were to upload local statutes and ordinances, issue warrants, punish and/or imprison those who break the statutes and ordinance, and ensure the quiet rule of Detroit. He was to execute legal documents in his role as notary.[14] Williams voted in the Detroit's first election that was held in 1768 to elect a judge and justice.[12] He was one of Detroit's town criers who passed on the news of the day by speaking to a crowd of people or by ringing a bell while walking through the streets and calling out the news.[15]

_Detroit%2C_p419_VIEW_OF_DETROIT_IN_1796%2C_FROM_THE_ORIGINAL_PAINTING_IN_PARIS.jpg)

Williams performed the census for Detroit in 1782 and calculated that there were 2,191 people compared to 1,367 in 1773. The totals do not include Indians or the garrison. Clarence M. Burton attributes the growth to people moving to the area to avoid the war. With the number of people in the garrison and those detained as prisoners of war and refugees, Burton estimates that there likely more than 3,000 people in Detroit in 1782.[16]

Personal life

Williams was married to Marie Cecile (commonly called Cecile or Cecelia) Chapeau[1][17] by A.S. DePeyster, commandant of Fort Detroit on May 7, 1781. It was one of Detroit's early Protestant marriages.[1][16] They were married by the commandant because they did not wish to be married by a Catholic priest. Their marriage certificate stated that the couple's relationship would be "conformable by the rule of the Church of England."[16] Cecile was from a prominent family. Her father was Jacques Chapeau[16] and her brothers were Barnabas, Denis, Joseph, Louis, Nicolas and Toussaint Chapeau.[4] Joseph was the state's first millionaire.[18] His mother's family had a French heritage and had been in Michigan since 1710.[13]

They had three children: Catherine, Elizabeth, and John R. Elizabeth taught in a Catholic school that co-founded with three other young women under the auspices of Gabriel Richard, a Detroit priest. She lived a single, chaste lifestyle.[4][18][lower-alpha 2] In 1809, Catherine married Jean Baptiste Peltier with whom she had two children.[4] John R. was the first mayor of Detroit, and served several of times more. He and his wife, Mary Mott Williams, had nine children.[4] Since Cecile was French Canadian, John R. spoke and wrote fluently in both French and English.[4][11]

Williams lived on Woodbridge Street in the 9th Ward in Detroit[20] and owned a lot of land in the area.[1] During the Revolutionary War, William's property in Albany was confiscated. He or his family later had the property returned to them.[18]

He died of the measles[21] on November 30, 1785.[7] On December 12 of the same year, Cecile leased a house from Joseph Campeau that was north of the Detroit River and adjacent to Joseph Campeau's property.[22] At the time of his death, much of his property was lost; there was just some property in Albany and a 600-acre farm on the Huron River of Lake St. Clair. Although these were significant holdings for the time, there was a large loss of his property, perhaps due to his wife's lavish lifestyle or the carelessness of Casety, his partner. Cecile and her children lived on the St. Clair property after Williams' death.[7]

In July 1790,[7] Cecile married Jaques Leson[19] (also spelled Loson[4] and Lauson[7]) and they lived in what is now St. Clair County, Michigan.[19] They had a daughter, Angelique.[19] Cecile died on June 24, 1805 and was buried in the St. Anne's church cemetery.[23]

Notes

- Burton states that Williams settled in Detroit during the Revolutionary War (1775-1783),[4] but he was involved in trade and had signed petitions by 1766.[5]

- Burton states that Elizabeth was born August 2, 1786 and was the daughter of Thomas and Cecile.[18] Thomas died before December 12, 1785 when Cecile was named as his widow on a lease.[19]

References

- Clarence Monroe Burton (1916). Manuscripts from the Burton Historical Collection. Collected and published by C.M. Burton. p. 337.

- "The Rev. G. Mott Williams, M.A.". The Churchman. Churchman Company. 1895. p. 709.

- Walter Scott Dunn (2005). People of the American Frontier: The Coming of the American Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0-275-98181-5.

- Clarence Monroe Burton; William Stocking; Gordon K. Miller (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. p. 1402.

- Walter Scott Dunn (2005). People of the American Frontier: The Coming of the American Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 102, 104, 107. ISBN 978-0-275-98181-5.

- Clarence Monroe Burton; William Stocking; Gordon K. Miller (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. p. 497.

- Historical Collections. 31. The Society. 1902. p. 315.

- Walter Scott Dunn (2005). People of the American Frontier: The Coming of the American Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-275-98181-5.

- Walter Scott Dunn (2001). The New Imperial Economy: The British Army and the American Frontier, 1764-1768. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-275-97180-9.

- Walter Scott Dunn (2001). The New Imperial Economy: The British Army and the American Frontier, 1764-1768. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-275-97180-9.

- "John R. Williams". History of Detroit. com. 2008. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- Clarence Monroe Burton; William Stocking; Gordon K. Miller (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. p. 170.

- "Rev. G. Mott Williams". Memorial Record of the Northern Peninsula of Michigan. Lewis Publishing Company. 1895. p. 370.

- Detroit Public Library (June 15, 1920). "Detroit in the Revolution: Proclamations of Sir Henry Hamilton". Library Service. 3. Detroit Public Library. pp. 2–3.

- Clarence Monroe Burton; William Stocking; Gordon K. Miller (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. p. 790.

- Clarence Monroe Burton; William Stocking; Gordon K. Miller (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. pp. 201–203.

- Silas Farmer (1890). History of Detroit and Wayne County and Early Michigan: A Chronological Cyclopedia of the Past and Present. S. Farmer & Company. p. 1021.

- Clarence Monroe Burton; William Stocking; Gordon K. Miller (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. p. 197.

- History of St. Clair County, Michigan: Containing an Account of Its Settlement, Growth, Development and Resources, Its War Record, Biographical Sketches, the Whole Preceded by a History of Michigan. A.T. Andreas & Company. 1883. p. 231.

- Journal of the Common Council of the City of Detroit: From the Time of Its First Organization. 1876. p. 217.

- Catherine Cangany (March 4, 2014). Frontier Seaport: Detroit's Transformation into an Atlantic Entrepôt. University of Chicago Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-226-09684-1.

- "Lease of House and Lot in Detroit". Historical collections. Collections and researches made by the Michigan pioneer and historical society. 8. Library of Congress. pp. 645, 1174. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- "People Buried from Ste. Anne de Detroit (1800-1805): Part VII" (PDF). Michigan’s Habitant Heritage. October 2011. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-17. Retrieved October 8, 2016.