Thomas Savery

Thomas Savery (/ˈseɪvəri/; c. 1650 – 1715) was an English inventor and engineer, born at Shilstone, a manor house near Modbury, Devon, England. He invented the first commercially used steam powered device, a steam pump which is often referred to as an "engine", although it is not technically an "engine". Savery's "engine" was a revolutionary method of pumping water, which solved the problem of mine drainage and made widespread public water supply practicable.

Thomas Savery | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1650 Shilstone, Modbury, Devon, England |

| Died | 1715 London |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Engineer |

Career

Savery became a military engineer, rising to the rank of Captain by 1702, and spent his free time performing experiments in mechanics. In 1696 he took out a patent for a machine for polishing glass or marble and another for "rowing of ships with greater ease and expedition than hitherto been done by any other" which involved paddle-wheels driven by a capstan and which was dismissed by the Admiralty following a negative report by the Surveyor of the Navy, Edmund Dummer.[1]

Savery also worked for the Sick and Hurt Commissioners, contracting the supply of medicines to the Navy Stock Company, which was connected with the Society of Apothecaries. His duties on their behalf took him to Dartmouth, which is probably how he came into contact with Thomas Newcomen.

First steam engine mechanism

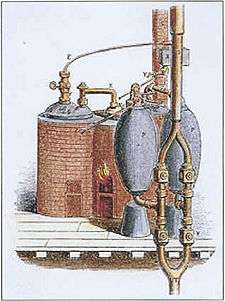

On 2 July 1698 Savery patented an early steam engine, "A new invention for raising of water and occasioning motion to all sorts of mill work by the impellent force of fire, which will be of great use and advantage for draining mines, serving towns with water, and for the working of all sorts of mills where they have not the benefit of water nor constant winds."[2] He demonstrated it to the Royal Society on 14 June 1699. The patent had no illustrations or even description, but in 1702 Savery described the machine in his book The Miner's Friend; or, An Engine to Raise Water by Fire,[3] in which he claimed that it could pump water out of mines.

Savery's engine had no piston, and no moving parts except from the taps. It was operated by first raising steam in the boiler; the steam was then admitted to one of the first working vessels, allowing it to blow out through a downpipe into the water that was to be raised. When the system was hot and therefore full of steam the tap between the boiler and the working vessel was shut, and if necessary the outside of the vessel was cooled. This made the steam inside it condense, creating a partial vacuum, and atmospheric pressure pushed water up the downpipe until the vessel was full. At this point the tap below the vessel was closed, and the tap between it and the up-pipe opened, and more steam was admitted from the boiler. As the steam pressure built up, it forced the water from the vessel up the up-pipe to the top of the mine.

However, his engine had four serious problems. First, every time water was admitted to the working vessel much of the heat was wasted in warming up the water that was being pumped. Secondly, the second stage of the process required high-pressure steam to force the water up, and the engine's soldered joints were barely capable of withstanding high pressure steam and needed frequent repair. Thirdly, although this engine used positive steam pressure to push water up out of the engine (with no theoretical limit to the height to which water could be lifted by a single high-pressure engine) practical and safety considerations meant that in practice, to clear water from a deep mine would have needed a series of moderate-pressure engines all the way from the bottom level to the surface. Fourthly, water was pushed up into the engine only by atmospheric pressure (working against a condensed-steam 'vacuum'), so the engine had to be no more than about 30 feet (9.1 m) above the water level – requiring it to be installed, operated, and maintained far down in the dark mines all over.

Fire Engine Act

Savery's original patent of July 1698 gave 14 years' protection; the next year, 1699, an Act of Parliament was passed which extended his protection for a further 21 years. This Act became known as the "Fire Engine Act". Savery's patent covered all engines that raised water by fire, and it thus played an important role in shaping the early development of steam machinery in the British Isles.

The architect James Smith of Whitehill acquired the rights to use Savery's engine in Scotland. In 1699, he entered into an agreement with the inventor, and in 1701 he secured a patent from the Parliament of Scotland, modelled on Savery's grant in England, and designed to run for the same period of time. Smith described the machine as "an engine or invention for raising of water and occasioning motion of mill-work by the force of fire", and he claimed to have modified it to pump from a depth of 14 fathoms, or 84 feet.[2][4]

In England, Savery's patent meant that Thomas Newcomen was forced to go into partnership with him. By 1712, arrangements had been between the two men to develop Newcomen's more advanced design of steam engine, which was marketed under Savery's patent, adding water tanks and pump rods so that deeper water mines could be accessed with steam power.[5] Newcomen's engine worked purely by atmospheric pressure, thereby avoiding the dangers of high-pressure steam, and used the piston concept invented in 1690 by the Frenchman Denis Papin to produce the first steam engine capable of raising water from deep mines.[6]

When Denis Papin was back to London in 1707, he was asked by Newton, new President of The Royal Society after Robert Boyle, Papin's friend, to work with Savery, who worked for 5 years with Papin, but never gave any credit nor revenue to the French scientist.

After his death in 1715 Savery's patent and Act of Parliament became vested in a company, The Proprietors of the Invention for Raising Water by Fire.[7] This company issued licences to others for the building and operation of Newcomen engines, charging as much as £420 per year patent royalties for the construction of steam engines.[8] In one case a colliery paid the Proprietors £200 per year and half their net profits "in return for their services in keeping the engine going".[9]

The Fire Engine Act did not expire until 1733, four years after the death of Newcomen.[10]

Application of the engine

A newspaper in March 1702 announced that Savery's engines were ready for use and might be seen on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons at his workhouse in Salisbury Court, London, over against the Old Playhouse.

One of his engines was set up at York Buildings in London. According to later descriptions this produced steam 'eight or ten times stronger than common air' (i.e. 8–10 atmospheres), but blew open the joints of the machine, forcing him to solder the joints with spelter.[11]

Another was built to control the water supply at Hampton Court, while another at Campden House in Kensington operated for 18 years.[12]

A few Savery engines were tried in mines, an unsuccessful attempt being made to use one to clear water from a pool called Broad Waters in Wednesbury (then in Staffordshire) and nearby coal mines. This had been covered by a sudden eruption of water some years before. However the engine could not be 'brought to answer'. The quantity of steam raised was so great as 'rent the whole machine to pieces'. The engine was laid aside, and the scheme for raising water was dropped as impracticable.[13][14] This may have been in about 1705.[14]

Another engine was proposed in 1706 by George Sparrow at Newbold near Chesterfield, where a landowner was having difficulty in obtaining the consent of his neighbours for a sough to drain his coal. Nothing came of this, perhaps due to the explosion of the Broad Waters engine.[14] It is also possible that an engine was tried at Wheal Vor, a copper mine in Cornwall.[15]

Comparison with Newcomen engine

The Savery engine was much lower in capital cost than the Newcomen engine, with a 2 to 4 horsepower Savery engine costing from 150-200 GBP.[16] It was also available in small sizes, down to one horsepower. Newcomen engines and early high pressure steam engines were larger and much more expensive. The larger size was due to the fact that piston steam engines became very inefficient in small sizes, at least until around 1900 when 2 horsepower piston engines were available.[17] Savery type engines continued to be produced well into the late 18th century.

Inspiration for later work

Several later pumping systems may be based on Savery's pump. For example, the twin-chamber pulsometer steam pump was a successful development of it.[18]

Notes

- Fox, Celina (2007). "The Ingenious Mr Dummer: Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England" (PDF). Electronic British Library Journal. p. 25. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- Jenkins, Rhys (1936). Links in the History of Engineering and Technology from Tudor Times. Ayer Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 0-8369-2167-4.

- Savery, Thomas (1827). The Miner's Friend: Or, an Engine to Raise Water by Fire. S. Crouch.

- The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, K.M. Brown et al eds (St Andrews, 2007–2013), date accessed: 24 June 2013.

- "Steam Condensate: Important Things to Know | DFT Valves". DFT Valves. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- L. T. C. Rolt and J. S. Allen, The Steam Engine of Thomas Newcomen (Landmark Publishing, Ashbourne 1997).

- Jenkins, pp. 78–79

- Oldroyd, David (2007). Estates, Enterprise and Investment at the Dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Ashgate Publishing Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 0-7546-3455-8.

- Roll, Eric (1968). An Early Experiment in Industrial Organisation. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 0-7146-1357-6.

- Armytage, W.H.G. (1976). A Social History of Engineering. Westview Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-89158-508-7.

- L.T.C. Rolt and J. S. Allen, The Steam Engine of Thomas Newcomen (Landmark Publishing, Ashbourne 2007), pp. 27–28

- E. I. Carlyle, 'Savery, Thomas (1650?–1715)', rev. Christopher F. Lindsey, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 29 April 2006 URL

- Richard Wilkes of Willenhall, quoted in Stebbing Shaw, History and Antiquities of Staffordshire (1798–1801) II(1), 120

- P. W. King. 'Black Country Mining before the Industrial Revolution' Mining History: The Bulletin of the Peak District Mines History Society 16(6), 42–3.

- Earl, Bryan (1994). Cornish Mining: The Techniques of Metal Mining in the West of England, Past and Present (2nd ed.). St Austell: Cornish Hillside Publications. p. 38. ISBN 0-9519419-3-3.

- Landes, David. S. (1969). The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present. Cambridge, New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. p. 62, Note 2. ISBN 0-521-09418-6.

- Hunter, Louis C.; Bryant, Lynwood (1991). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730-1930, Vol. 3: The Transmission of Power. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press. p. xxi. ISBN 0-262-08198-9.

- "SPP Pumps". spppumps.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006.

Further reading

- Savery, Thomas (1827). The Miner's Friend: Or, an Engine to Raise Water by Fire. S. Crouch.

- Smiles, Samuel (1865). Lives of Boulton and Watt. Lippincott.

- There are countless modern day reprints: Lives of Boulton and Watt. ISBN 1-4255-6053-9., Lives of Boulton and Watt. ISBN 1-4067-9863-0., Lives of Boulton and Watt. ISBN 1-84588-371-3..

- Reprinted in Appendix B of: Savary, A.W.; Lydia A. Savary (1893). A Genealogical and Biographical Record of the Savery Families and of the Severy Family. Lippincott.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1885–1900 Dictionary of National Biography's article about Thomas Savery. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Savery |

- Diagram of Savery's pump at the Wayback Machine (archived 14 August 2007)

- Works by or about Thomas Savery in libraries (WorldCat catalog)