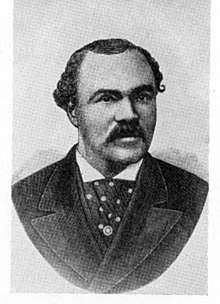

Thomas Bowers (singer)

Thomas J. Bowers (c. 1823–October 3, 1885),[1] also known as "The Colored Mario",[2] was an American concert artist. He studied voice with African-American concert artist Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and toured with her troupe for a few years before embarking on his own successful solo career. He was the brother of professional singer Sarah Sedgwick Bowers, known as "the Colored Nightingale",[1] and John C. Bowers, a Philadelphia entrepreneur and church organist.

Thomas J. Bowers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Thomas J. Bowers |

| Born | c. 1823 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | October 3, 1885 Pennsylvania |

| Occupation(s) | Concert artist |

| Years active | 1854–85 |

A fictionalized version of Thomas Bowers' life was depicted by actor William Marshall in a 1964 episode of Bonanza titled "Enter Thomas Bowers".

Early life

Thomas Bowers was born in 1836 in Philadelphia. His father, John C. Bowers, Sr. (1773-1844), was a secondhand clothing dealer, a vestryman and school trustee at St. Thomas African Episcopal Church, and one of the founders of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.[3]:133[4] His mother's name was Henrietta.[3]:153 As a youngster, Thomas showed a desire to learn music and was taught piano and organ by his older brother John.[1] At the age of 18, he succeeded his brother as organist of St. Thomas African Episcopal Church.[5] He and his brother were trained as tailors and operated a "fashionable merchant tailor shop" catering to upper class gentlemen and businessmen in Philadelphia.[6]

Concert artist

Despite his natural aptitude for music and enjoyment of singing, Bowers deferred to his parents' wishes not to perform outside the church. He declined offers to sing with the famous Frank Johnson's Band of Philadelphia, among others.[5] But as more people became acquainted with his singing, he was persuaded to appear at a Philadelphia recital in 1854 with African American concert artist Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, and became her student in voice.[5] That 1854 appearance met with popular and critical success; the critics began calling him "The Colored Mario" and "The American Mario" for the similarity of his voice to Italian opera tenor Giovanni Mario.[1][7] Bowers personally disliked the sobriquet,[8] but agreed to be billed as "Mareo".[5] He proceeded to tour with Greenfield's troupe in Philadelphia, the Midwestern United States, New York, and Canada,[7] and afterwards embarked on a successful solo career.

Bowers specialised in "romantic ballads and popular arias from well-known operas".[8] His voice was described as having a "wonderful power and beauty"[7] and "extraordinary power, mellowness, and sweetness".[9] His range was nearly two octaves.[5] He was said to be "handsome" and had a strong stage presence.[5][9]

Bowers found the stage an ideal platform from which to espouse his opposition to racial inequality. He was purportedly reluctant to launch a public singing career until he realised: "What induced me more than any thing else to appear in public was to give the lie to 'negro serenaders' (minstrels), and to show to the world that coloured men and women could sing classical music as well as the members of the other race by whom they had been so terribly vilified".[10] He became famous for refusing to perform before segregated or white-only audiences.[7][9] For an 1855 performance in Hamilton, Ontario, where the theatre manager refused to seat six black patrons who had purchased reserved first-class seats, Bowers refused to perform.[1][2][7]

Trotter writes: "Mr. Bowers, during his career, has sung in most of the Eastern and Middle States; and at one time he even invaded the slavery−cursed regions of Maryland. He sang in Baltimore, the papers of which city were forced to accord to him high merit as a vocalist."[5]

Bowers also appeared at benefit concerts to raise funds for the recruitment of black soldiers to the Union Army training camp at Camp William Penn.[11]

Other activities

Together with other members of his family, Bowers was a national organiser of "black opposition to the fugitive slave laws of the 1850s and a state representative of the Equal Rights Convention.[12] In October 1864 he was a delegate from Philadelphia to the National Convention of Coloured Men in Syracuse, New York.[13]

Personal

Bowers married Lucretia Turpin, a native of New York, sometime before 1850.[12][14] They had one daughter, Adelia.[12]

At the time of his death in 1885, he possessed "nearly $10,000 in real estate, Pennsylvania Railroad stock, household furnishings and cash in the Farmers and Mechanics Bank".[12]

Bonanza episode

In a 1964 episode of Bonanza titled "Enter Thomas Bowers", Thomas was portrayed by African American opera singer and actor William Marshall.[1]

References

- Nettles, Darryl Glenn (2003). African American concert singers before 1950. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 0786414677.

- Washington, Linn; Lawrence, Bette Davis (8 February 1988). "Philadelphia's Black Elite In The Shadows Of History 1840-1940". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Winch, Julie (2000). The Elite of Our People: Joseph Willson's Sketches of Black Upper-Class Life in Antebellum Philadelphia. Pennsylvania State University. ISBN 0271020202.

- Foner, Philip Sheldon (1983). History of Black Americans: From the emergence of the cotton kingdom to the eve of the compromise of 1850. Greenwood Press. p. 310. ISBN 0837175291.

- Trotter, James Monroe (1881). "Thomas J. Bowers, Tenor-Vocalist; Often styled the "American Mario"". Music and Some Highly Musical People. Johnson reprint. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Delany, Martin Robison (2012). The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States. Tredition. ISBN 3847207970.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Jr., Henry Louis (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 598. ISBN 0195170555.

- Price, III, Emmett G.; Kernodle, Tammy; Maxille, Horace (2010). Encyclopedia of African American Music. ABC-CLIO. p. 244. ISBN 0313341990.

- Brawley, Benjamin Griffith (1966). The Negro Genius: A New Appraisal of the Achievement of the American Negro in Literature and the Fine Arts. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. p. 99. ISBN 9780819601841.

- Schenbeck, Lawrence (2012). Racial Uplift and American Music, 1878-1943. University Press of Mississippi. p. 50. ISBN 1617032301.

- Scott, Sr., Donald (2008). Camp William Penn. Arcadia Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 9780738557359.

- Lapsansky, Emma Jones (January 1984). "Friends, Wives, and Strivings: Networks and Community Values Among Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia Afroamerican Elites". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography: 20–21.

- Matthews, Harry Bradshaw (2008). African American Freedom Journey in New York and Related Sites, 1823-1870: Freedom Knows No Colour. Africana Homestead Legacy Pb. pp. 213–215. ISBN 9780979953743.

- Autobiography of Dr. William Henry Johnson. Haskell House Publishers Ltd. 1900. p. 116.

Further reading

- Cheatham, Wallace (1997). Dialogues on Opera and the African-American Experience. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810831473.

- Southern, Eileen (1997). The Music of Black Americans: A History. W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393038432.

- Trotter, James M. (1881). Music and Some Highly Musical People.