Theodore Palaiologos (stratiote)

Theodore Palaiologos (Italian: Teodoro Paleologo, Greek: Θεόδωρος Παλαιολόγος, romanized: Theodōros Palaiologos; 1452–1532) was a 15th- and 16th-century Greek stratiote (light-armed mercenary cavalryman) and diplomat in the service of the Republic of Venice and one of the key early formative figures of the Greek community in Venice. He was not related to the Palaiologos dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, but his family may have been their distant cousins.

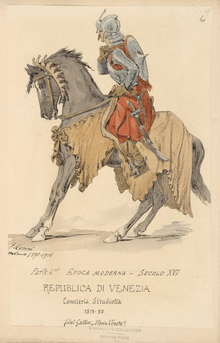

Theodore Palaiologos | |

|---|---|

Portrait of a stratiote, believed to be Theodore Palaiologos | |

| Native name | Theodōros Palaiologos |

| Other name(s) | Teodoro Paleologo |

| Born | 1452 Mystras, Despotate of the Morea |

| Died | 1532 (aged c. 80) Venice |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Stratioti |

| Years of service | 1478–1525 |

| Rank | Capo dei stratioti |

| Awards | Order of Saint Mark |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Kantakouzene |

| Children | Paolo Paleologo Demetri Paleologo Efrosina Paleologo Emilia Paleologo Lucia Paleologo Helena Paleologo Nicolosa Paleologo Another daughter (name unknown) |

| Relations | Paulos Palaiologos (father) Georgios Palaiologos (brother) Matthew Palaiologos (brother) A sister (name unknown) |

Originally a soubashi (debt-collector/police enforcer) in Ottoman service in the Peloponnese, Theodore left Greece in 1478. He would serve as a stratiote for more than forty years, partaking in numerous battles and campaigns and would also serve as a military governor on the Venetian-held Greek island of Zakynthos for thirty years, from 1483 to 1513. As one of the most respected Greeks in Venice, the esteem held for Theodore by the Venetian government is probably what led to the Venetians allowing the local Greeks to construct their own Greek Orthodox church, San Giorgio dei Greci, in the city. After giving up soldiering in 1525, Theodore served as a diplomat and translator, and since he could speak Italian, Greek and Turkish, he accompanied Venetian ambassadors to the Ottoman Empire several times.

Biography

Background and early life

Theodore Palaiologos was born in 1452,[1] the son of Paulos Palaiologos.[1][2] Paulos was probably from the Morea (the medieval name for the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece) and Theodore was likely born at Mystras, the peninsula's capital.[1][2][3] They shared their last name with the Palaiologos dynasty, the final ruling dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, but are unlikely to have been related to the imperial family.[2] The Palaiologos family had been extensive even before they became the empire's ruling dynasty,[3] so it is plausible that Theodore and his family were distant cousins of the emperors. Theodore had three siblings; Georgios (Giorgio or Zorzi in Italian), Matthew (who would become the abbot of a monastery on Zakynthos) and a sister whose name remains unknown.[2]

In his youth, Theodore originally worked as a soubashi (debt-collector/police enforcer) in the Peloponnese on behalf of the Ottoman Empire, which conquered the Morea in 1460, before he, his father,[1] and his brother Georgios,[2] took up service with the Republic of Venice as stratioti (light-armed mercenary cavalrymen)[1][3] in 1478.[1] In due time, Paulos, Theodore and Georgios would all rise through the ranks to become capo dei stratioti ("head of the stratioti").[2]

Career as a stratiote

One of the earliest preserved references to Theodore is a 1479 decision by the Venetian Senate concerning him, which states that he had recently proven himself in battle on a campaign in Friuli.[2]

In 1483, Theodore and his brother Georgios were appointed as military governors on the Venetian-held Greek island of Zakynthos, being granted grand properties and salaries.[2]

On 15 November 1486, Theodore married Maria Kantakouzene in Corfu. She was the daughter of a Demetrios Kantakouzenos and a woman by the name of Simone Gudellina. Since Maria and her father appears to have been genuine members of the noble Byzantine Kantakouzenos family, Theodore's branch of the Palaiologoi must have had a certain noble status. Theodore and Maria had two sons; Paolo and Demetrio, and six daughters; Efrosina, Emilia, Lucia, Helena, Nicolosa and a sixth daughter whose name is unknown.[2]

In 1489, Theodore was granted the small island of Cranae by the Venetian government, but he soon ceded it to another family. In the autumn of 1495, he was present at a siege of Novara, where the Venetians attempted to take the city from France. In March 1496, Theodore was one of the c. 250 stratioti who accompanied Venetian naval captain Domenico Malipiero in a campaign in Savona. In 1500 he partook in the Siege of the Castle of Saint George on the island of Cephalonia. In December 1502, Theodore was captured at Canosa di Puglia by French troops, though he was soon freed. In February 1503, he was fighting alongside c. 300 other stratioti in Calabria. In August 1511 he was stationed as a guard at Treviso, and from 1511 to 1512 he is recorded as travelling around Italy, serving as a guard and scout. Theodore was taken captive at the Battle of La Motta (7 October 1513), but was released at the end of the month.[1]

In 1513, there was an earthquake on Zakynthos. Theodore's wife Maria died, their youngest daughter was maimed and their son Demetri was injured. Theodore decided to move both his own family, and the family of his brother Georgios, who had been killed in battle near Bressano in 1497, to Venice. Theodore had to look after and support his own eight underage children, Georgios's widow, Theodore, and Georgios's and Theodora's six children; Costantino, Niccolò, Zuanne, Alessandro, Elisabeta and a daughter of unknown name. After Theodore's oldest son Paolo was killed in 1525, Theodore also had to look after Paolo's wife, Emilia, and their six daughters. The large number of people he quickly became responsible for might be why Theodore gave up soldiering.[2]

Later life

After 1525, Theodore became a diplomat in Venetian service. In addition to Greek and Italian, he also spoke Ottoman Turkish, and he frequently accompanied Venetian ambassadors and other officials on their visits to the eastern Mediterranean. Because they could speak Turkish, Theodore and his nephew Costantino (son of his brother Georgios) served as dragomani (translators/interpreters) for Ottoman dignitaries visiting Venice.[4] Theodore had prior knowledge of diplomacy, having accompanied the Venetian ambassador Alvise Maneti to the Ottoman court in Adrianople in March 1500. In 1517, he was recorded as on a diplomatic mission to Constantinople, the Ottoman (and former Byzantine) capital.[1] On account of his years of military service and his work as a diplomat and translator, the Venetian government awarded Theodore with their highest honor; bestowing upon him a Knighthood of Saint Mark.[4]

In addition to serving as a diplomat, Theodore also devoted himself to the Greek community in Venice, of which Theodore was one of the early key formative figures. The local Greeks had been petitioning the Venetian government for a Greek Orthodox church in the city since 1511, a cause which Theodore championed for years, regularly visiting officials and urging them to hand down a resolution. He was admired and respected by the other Greeks in the city. The esteem the Venetian government had for him is likely what eventually resulted in the construction of an Orthodox church in the city.[4]

Theodore was often called upon to settle disputes between towns and their hired stratioti, or between different quarreling bands of stratioti. In 1524, the town of Cattaro appealed to the Venetian government that their stratiote and military governor, Zuanne Paleologo (another son of Theodore's brother Georgios) spent most of his time in Cephalonia, away from the town he was supposed to protect. The people of Cattaro explicitly asked for "Teodoro Paleologo, a loved and much desired man" to travel to Cattaro and restore order.[4] The Venetian senate agreed and on 2 September 1424, Theodore and his son Demetri were sent to Cattaro to replace Zuanne.[5]

Theodore died in 1532.[3] His funeral took place on 3 September that same year and was a grand ceremony. His coffin was carried by a guard of honor of mariners to the temporary structures on the site were the city's Greek Orthodox church, San Giorgio dei Greci, was being built. Despite the building being a Greek Orthodox structure, representatives from local Roman Catholic churches, and other religious representatives, were present, as were dignitaries from the Venetian government. The funeral was held according to Greek rite, the customs of which were adhered to even by the Catholics present.[5]

References

- Damiani.

- Burke 2014, p. 121.

- Nicol 1992, p. 117.

- Burke 2014, p. 122.

- Burke 2014, p. 123.

Cited bibliography

- Burke, Ersie (2014). "Surviving Exile: Byzantine Families and the Serenissima 1453–1600". In Nilsson, Ingela; Stephenson, Paul (eds.). Wanted: Byzantium: The Desire for a Lost Empire. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-9155489151.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1992). The Immortal Emperor: The life and legend of Constantine Palaiologos, last Emperor of the Romans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41456-3.

Cited web sources

- Damiani, Roberto. "Teodoro Paleologo Greco". Condottieri di ventura (in Italian). Retrieved 2020-06-17.