The Wounded Montenegrin

The Wounded Montenegrin (Serbian: Рањени Црногорац, Ranjeni Crnogorac) is the title of four nearly identical compositions by the artist Paja Jovanović depicting a wounded youth surrounded by peasants in traditional clothing, likely during the Montenegrin–Ottoman War of 1876–78.

The first rendering garnered praise from critics, and won the first-place prize at the Academy of Fine Arts' annual art exhibition in Vienna in 1882. Given its success, Jovanović was granted an Austro-Hungarian government scholarship and entered into a contract with the French Gallery in London to produce a series of paintings on Balkan life. Art historians consider The Wounded Montenegrin one of Jovanović's best Orientalist works. Jovanović went on to complete three further versions of the composition in the ensuing decades, three of which are oil paintings. The first is currently on display at the Matica Srpska gallery in Novi Sad, the second and third are in private collections, and the fourth is housed at the Museum of Yugoslav History in Belgrade.

Description

The original oil painting measures 114 by 189 centimetres (45 in × 74 in).[lower-alpha 1] It shows a muscular, wounded youth surrounded by ten peasants in a humble, single-room dwelling.[2] The peasants wear hand-sewn shirts, rough leggings and leather shoes. They stand over a dirt floor, and in the background, a collection of eating utensils hang precariously from a makeshift shelf. The youth is cradled in the arms of a crouching, shaved-headed warrior. The two are surrounded by a pair of heavily armed men on either side of them.[3] Nearby, a light-haired girl quietly grieves. To the right of these figures stands a grief-stricken old man, himself surrounded by a number of figures in folk attire.[2] To the far right, two figures can be seen standing inauspiciously in the shadows. The artist's signature, rendered as Joanowits P., can be found at the bottom right.[4]

Jovanović composed a total of four versions of The Wounded Montenegrin, three oil paintings and one sketch. What distinguishes the first rendering from subsequent versions is its size (it is the largest by far), detailed precision, and the artist's removal of the two figures seen lingering in the shadows in the original.[4] The second version, an oil painting, measures 100 by 152 centimetres (39 in × 60 in). The artist's signature, P. Ivanovitch, can be seen at the bottom right.[5] The third rendition is a sketch measuring 23 by 35 centimetres (9.1 in × 13.8 in), with the artist's signature, Pa. Jo., at the bottom right.[6] The fourth version, another oil painting, measures 70 by 103 centimetres (28 in × 41 in). The artist's signature, Paul Ivanovitch, can be seen at the bottom right.[5]

Jovanović did not assign titles to his works, as he felt that if a painting was well composed viewers would be able to deduce the title themselves. Thus, the majority of the artist's works are referred to by a number of different titles.[7] The Wounded Montenegrin also appears under the titles The Wounded Herzegovinian (Ranjeni Hercegovac), The Wounded Bosnian (Ranjeni Bosanac), Sad Encounter (Žalosni susret), Sad Farewell (Žalosni rastanak) and Unsuccessful Banditry (Neuspelo razbojništvo).[4]

History

Background

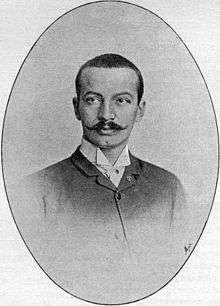

Paja Jovanović (1859–1957) was one of the most prominent Serbian realist painters of the late 19th century.[8] During his early career, he came to be identified with Orientalist painting, depicting scenes from the Balkans, which were then under the control of the Ottoman Empire.[2] Between 1877 and 1882, he attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where he came under the mentorship of painting instructors Christian Griepenkerl and Leopold Müller. Griepenkerl taught the young Jovanović the underlying structural principles of Renaissance and Baroque art, thus helping him better understand spatial problems and the arrangement of large numbers of figures, both moving and static. Müller encouraged Jovanović to take a naturalist approach to painting, recording only what he could see and relying as little as possible on his imagination. It was in this context that Müller instructed Jovanović to make direct studies of Balkan life during his visits home, purposely steering him towards Orientalist painting.[9]

Orientalist works, vignettes of "exotic life" in the Middle East, North Africa and the Balkans, were quite popular with Central and Western European art collectors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At the time of The Wounded Montenegrin's composition, events in the Balkans had been making headline news in European capitals for decades.[3] The Montenegrins had fought and lost the 1861–62 Montenegrin–Ottoman War. This was followed by about a decade of peace, but in 1872, the Ottomans massacred more than 20 Montenegrins. The Herzegovina Uprising of 1875 prompted Montenegro and Serbia to declare war on the Ottoman Empire, sparking the Great Eastern Crisis of 1875–78. The wars ended in the Treaty of Berlin in 1878, but occasional cross-border skirmishing continued until the early 1880s.[2] Although Jovanović never specified, it is likely the painting is set during the 1876–78 Montenegrin–Ottoman War.[3]

Provenance

Jovanović composed the first, and most famous, version of The Wounded Montenegrin in 1882 while studying at the Vienna Academy. It was sold to a merchant named Schwartz in Vienna later that year. Within several months, Schwartz sold the painting to a Budapest casino for 1,000 florins. After World War II, it came into the possession of the Yugoslav embassy in Budapest, which gifted it to the Matica Srpska gallery in 1971, where it is on permanent display. It is catalogued under inventory code ГМС Y/3912.[4]

The second version of The Wounded Montenegrin was composed in 1891. It was initially owned by Arthur Toot & Sons, a London art dealer, before coming into the possession of the Salon. Afterwards, it entered into a private collection, and remained in private ownership until 1989, when it was auctioned off at Sotheby's. Between 1989 and 1997, it was housed at a museum in Rome, but sold again thereafter. It is currently in a private collection.[5]

The third version, composed after 1900, is part of a private collection.[6] The fourth, painted in the 1920s, was in a private collection until World War II. After the war, it was confiscated by the communists. Following the death of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito, it was put on display at Tito's mausoleum, the House of Flowers. It is currently on display at the Museum of Yugoslav History, and catalogued under the inventory code 59 R.[5]

Analysis

In line with Müller's advice, Jovanović avoided creating a sentimental work and focused instead on depicting characters and situations he observed during his time in the Balkans. This differentiates the painting from other Orientalist paintings of the day, which were based on travel accounts rather than first-hand experience.[3] The art historian Lilien Filipovitch-Robinson notes that the grouping of the figures and their interactions with one another are reminiscent of images of the lamentation over the body of Christ.[2] The right half of the scene recedes into shadow while the brightly illuminated left, where the principal figures are located, appears to expand towards the viewer. Jovanović thus directs the viewer's eye from left to right, foreground to background, through the circular pattern of the groupings as well as the diagonal lines of the peasants' swords. In line with Müller's teachings regarding light and colour, Jovanović adds touches of bright red to give warmth and movement to the scene, making it appear as though it is unfolding before the viewer. The brushwork is varied, ranging from the smooth broad strokes that define the solidity of the walls to quick short ones that make it appear like the figures are in motion.[10]

Filipovitch-Robinson praises Jovanović's "skillful handling" of linear and aerial perspective. She notes that the work is devoid of the "studio-contrived quality" of other Orientalist paintings, and argues that Jovanović's main goal was not to depict a particular historical event but rather to remind his audience of the Balkan peoples' ongoing struggle against the Ottoman Turks and provide a human face to those engaged in that struggle.[10]

Reception and legacy

The painting was first shown in public in 1882, at the Vienna Academy's annual student exhibition, which exhibited works produced during the 1881–82 academic year.[4] It was well received by art critics and Jovanović's peers, who judged it to be the exhibition's finest work and bestowed him the first-place prize.[11] Jovanović also received an Austro-Hungarian government scholarship. The exact amount accorded to the artist is disputed. Petar Petrović, the curator of the National Museum of Serbia, writes that the scholarship amounted to 300 florins.[4] Art historians Radmila Antić[12] and Nikola Kusovac[13] state the scholarship amounted to 1,000 florins. Jovanović's triumph at the student exhibition and the subsequent scholarship gave him the means to travel over the summer holidays, during which he came up with a number of ideas for future paintings, such as The Fencing Lesson (Mačevanje).[13] Winning the Vienna Academy prize established him as a respected painter of Orientalist works and set the stage for further recognition and success.[3] In 1883, Jovanović entered into a contract with Ernest Gambart's French Gallery in London to produce a series of paintings on Balkan life.[14] This contract assured him lifelong financial security.[15]

Art historians consider The Wounded Montenegrin to be one of Jovanović's best Orientalist works.[16] Petrović calls it the "crowning achievement" of the artist's studies under Müller.[4] Jovanović went on to paint a number of other Orientalist pieces, notably The Snake Charmer (1887).[17]

References

Endnotes

- Filipovitch-Robinson gives the dimensions as 114 by 186 centimetres (45 in × 73 in).[1]

Citations

- Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 45.

- Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 39.

- Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 44.

- Petrović 2012, p. 16.

- Petrović 2012, p. 44.

- Petrović 2012, p. 41.

- Kusovac 2012, p. 118, note 156.

- Jelavich & Jelavich 1977, p. 280.

- Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 43.

- Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 40.

- Antić 1970, p. 30.

- Antić 1970, p. 31.

- Kusovac 2009, p. 35.

- Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 46.

- Filipovitch-Robinson 2007, p. 122.

- Antić 1970, p. 31; Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 39.

- Popović 2014, pp. 27–31.

Bibliography

- Antić, Radmila (1970). Paja Jovanović. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Belgrade City Museum. OCLC 18028481.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien (2007). "Exploring Modernity in the Art of Krstić, Jovanović and Predić" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers. 21 (1): 115–35. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien (2008). "Paja Jovanović and the Imagining of War and Peace" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers. 22 (1): 35–53. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-08.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien (2014). "From Tradition to Modernism: Uroš Predić and Paja Jovanović". In Bogdanović, Jelena; Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien; Marjanović, Igor (eds.). On the Very Edge: Modernism and Modernity in the Arts and Architecture of Interwar Serbia (1918–1941). Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. ISBN 978-90-5867-993-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1977). The Establishment of the Balkan National States: 1804–1920. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80360-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kusovac, Nikola (2009). Паја Јовановић [Paja Jovanović] (in Serbian). Belgrade: National Museum of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-80619-55-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petrović, Petar (2012). Паја Јовановић: Систематски каталог дела [Paja Jovanović: A Systematic Catalogue of His Works] (in Serbian). Belgrade: National Museum of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-7269-130-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Popović, Radovan (2014). "Разматрање формално-композиционих карактеристика оријенталистичких слика Паје Јовановића" [An Analysis of Formal Compositional Characteristics in the Orientalist Paintings of Paja Jovanović] (PDF) (in Serbian). Novi Sad, Serbia: University of Novi Sad. ISSN 2334-8666. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)