The White Doe of Rylstone

The White Doe of Rylstone; or, The Fate of the Nortons is a long narrative poem by William Wordsworth, written initially in 1807–08, but not finally revised and published until 1815. It is set during the Rising of the North in 1569, and combines historical and legendary subject-matter. It has attracted praise from some critics, but has never been one of Wordsworth's more popular poems.

Synopsis

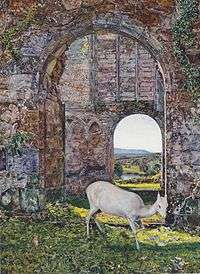

The White Doe of Rylstone opens outside Bolton Abbey in Wharfedale, where the poet sees the white doe enter the churchyard and lie down by one particular grave, where it is recognized as a regular visitor by the parishioners. The poem then moves back in time to Emily Norton at Rylstone Hall; at her father's command she embroiders a banner for his followers, who are to rise in rebellion. Emily's brother Francis tries unsuccessfully to dissuade their father from this course, then resolves to follow them unarmed, in the hope that he can still dissuade his father. Norton's band of soldiers, including other brothers of Emily, joins forces with those of the Earl of Northumberland and other Catholic rebels, and they march to Wetherby. On the approach of Queen Elizabeth's army the rebels fall back in retreat. The poem then returns to Rylstone Hall, where Emily encounters the white doe by moonlight. She sends an old friend of her father to get news of his fate; he returns to say that her father is taken prisoner, and that he has told Francis to regain the banner and take it to Bolton Abbey, where it can serve as an emblem of the purity of his motives. Richard almost accomplishes this task, but he is surprised by a party of the royal army and is killed. When Rylstone Hall suffers devastation Emily flees, and only returns years later, there to find the same white doe, which henceforth becomes her faithful friend, going wherever she goes. Emily at last dies and is buried at Bolton Abbey. The mystery of why the white doe visits the grave is thus explained.

Sources

It has been argued that Wordsworth was induced to write a historical poem by observing the success of Walter Scott's The Lay of the Last Minstrel. Wordsworth found in Thomas Whitaker's The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven the legend of a white doe which, after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, continued to make a weekly pilgrimage from Rylstone to Bolton Abbey.[1] The historical parts of the story of The White Doe are taken from a ballad called "The Rising in the North", which Wordsworth had read in Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, and also from Nicolson and Burn's The History and Antiquities of the Counties of Westmorland and Cumberland. The influence of other ballads from Percy's Reliques has also been traced in the poem, and the dedicatory poem to The White Doe is filled with references to Spenser's The Faerie Queene.[2][3] The metre of the poem is similar to that of Coleridge's Christabel, and Wordsworth acknowledged his debt to it in a preface, but Scott, Virgil and Samuel Daniel have also been cited as possible influences on the metre.[4][5]

Composition and publication

In June 1807 Wordsworth and his sister visited Bolton Abbey. Later that year he read Whitaker's account of the legend of the white doe, and, in October 1807, began to write The White Doe, finally completing it on 18 January 1808.[6][7] In February 1808 Wordsworth visited London to consult Coleridge about The White Doe, and to try to sell it for, Wordsworth hoped, 100 guineas. Together the two dined with the publisher Longman to discuss the poem, then Wordsworth returned home, leaving the manuscript with Coleridge so that he could show it to Charles Lamb (who professed himself dissatisfied with the inactivity of the main characters) and continue negotiations with Longman. Dorothy Wordsworth, acutely aware of the need for money in the Wordsworth household, wrote to Coleridge to urge on his efforts.[8][9][10] Three months later Coleridge was surprised and annoyed to discover that Wordsworth had written to Longman to the effect that he had decided not to publish the poem. When Coleridge protested to Wordsworth his objections were swept aside, provoking a serious quarrel between the two friends.[11][12] Wordsworth's reason for withdrawing The White Doe may have been his dismay at the appalling reviews of his Poems, in Two Volumes; at any rate he remained unwilling to publish the poem for several more years.[13] By 1815 however Wordsworth had come up with a revised and expanded text, for which he wrote a dedication to his wife Mary in Spenserian metre, completing it on 20 April. It was published in quarto, priced at one guinea, on 2 June.[14][15]

Reception

Wordsworth himself believed The White Doe to be one of his finest poems, but the reviewers were at best lukewarm. The Eclectic Review did concede that "where he comes in contact with the ordinary sympathies of human nature, no living poet leaves so strongly the impression of a master genius", but Francis Jeffrey of the Edinburgh Review, a long-time foe of the Lake Poets, thought it had "the merit of being the very worst poem we ever saw imprinted in a quarto volume".[16] Coleridge, by then in a state of uneasy reconciliation with Wordsworth, quoted a passage from The White Doe in his Biographia Literaria, praising its beauty and imaginative power.[17][18] John Ruskin, in a private letter, compared it favourably with Coleridge's Christabel, calling it "a poem of equal grace and imagination, but how pure, how just, how chaste in its truth, how high in its end".[19] Later in the century Leslie Stephen thought that the poem unduly exalted passive heroism at the expense of active heroism, and thought its "rough borderers" unlikely mouthpieces for Wordsworth's message of quietism and submission to circumstances. His wry comment was that "The White Doe is one of those poems which make many readers inclined to feel a certain tenderness for Jeffrey's rugged insensibility; and I confess that I am not one of its warm admirers".[20] In the 20th century the critic Alice Comparetti and the poet Donald Davie were agreed in finding in The White Doe the melancholy of Thomson, Gray and Milton. Davie praised the purity of the poem's diction, which he thought unequalled in any other long Wordsworth poem; he summarised it as "impersonal and self-contained, thrown free of its creator with an energy he never compassed again".[21]

The critical verdict has therefore been mixed. Among the reading public it has never been one of Wordsworth's most popular poems, perhaps because his lofty conception of The White Doe led him to make few concessions to the ordinary poetry-reader.[2][4]

Notes

- Moorman 1968, p. 110.

- Gill 1990, p. 261.

- Comparetti, Alice Pattee, ed. (1940). The White Doe of Rylstone by William Wordsworth. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. pp. 110–115.

- Davie 1972, p. 359.

- Moorman 1968, pp. 112-113, 121.

- Pinion 1988, p. 72.

- Moorman 1968, pp. 108, 110.

- Holmes 1999, pp. 122-123, 125-126.

- Gill 1990, p. 262.

- Moorman 1968, p. 120.

- Holmes 1999, pp. 138-139.

- Pinion 1988, p. 74.

- Gill 1990, pp. 266-268.

- Pinion 1988, pp. 97-98.

- Moorman 1968, p. 283.

- Moorman 1968, p. 284.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1991) [1906]. Watson, George (ed.). Biographia Literaria, or Biographical Sketches of My Literary Life and Opinions. London: Everyman's Library. pp. 273–275. ISBN 0460871080. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Moorman 1968, p. 311.

- Ruskin, John (1972). "From a Letter to the Rev. Walter Brown". In McMaster, Graham (ed.). William Wordsworth. Penguin Critical Anthologies. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 179. ISBN 0140806695. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Stephen, Leslie (1972). "From "Wordsworth's Ethics"". In McMaster, Graham (ed.). William Wordsworth. Penguin Critical Anthologies. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 216. ISBN 0140806695. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Davie 1972, pp. 361, 362, 364.

References

- Davie, Donald (1972). "From "Diction and Invention: Wordsworth"". In McMaster, Graham (ed.). William Wordsworth. Penguin Critical Anthologies. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0140806695.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gill, Stephen (1990) [1989]. William Wordsworth: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192827472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Richard (1999) [1998]. Coleridge: Darker Reflections. London: Flamingo. ISBN 0006548423.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moorman, Mary (1968) [1965]. William Wordsworth: A Biography. The Later Years, 1803-1850. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198811462.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pinion, F. B. (1988). A Wordsworth Chronology. Boston: G. K. Hall. ISBN 0816189501.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)