The Third Bullet

The Third Bullet: the political background of the assassination of Zoran Đinđić (Serbian: Treći metak: politička pozadina ubistva Zorana Đinđića) is a 2014 non-fiction book written by security officer Milan Veruović and journalist Nikola Vrzić. It analyzes the events surrounding the assassination of Zoran Đinđić and gives views on the political background of the assassination.

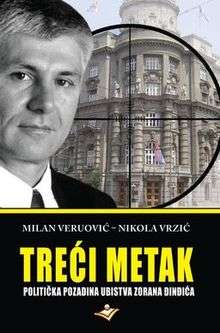

Cover page of the first edition | |

| Author | Milan Veruović, Nikola Vrzić |

|---|---|

| Original title | Treći metak: politička pozadina ubistva Zorana Đinđića |

| Country | Serbia |

| Language | Serbian |

| Subject | Assassination of Zoran Đinđić |

| Publisher | Pi-Press Books, Rotografika Subotica |

Publication date | 5 September 2014 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 446 pp (hardcover) |

| ISBN | 978-86-80008-00-4 |

Background

1990s: Yugoslav Wars

The Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, and the sanctions which were imposed on Serbia as the main federal state of SFR Yugoslavia, severely hit the state economy. The 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia also much contributed to the failed economy. Hyperinflation, restrictions on fuel, electricity, water, cigarettes and lack of basic foodstuffs, high unemployment and general deterioration of society, led to many illegal activities, grey market and massive smuggling activities. Also, criminal and murder rates increased to their highest levels.

The opposition parties in Serbia, most notably Serbian Renewal Movement and Democratic Party, have organised many massive protests during the 1990s. On 5 October 2000, Yugoslav president Milošević was overthrown in a massive protest on presidential results. Serbian elite police unit JSO, operated under the command of State Security Service during the 1990s, and its leader at the time Milorad Ulemek had a major role in the overthrow of Milošević, to whom the unit was loyal in the past and executed many operations for him; some, including Vuk Drašković dubbed the unit as "Milošević's squadrons of death" (see Ibar Highway assassination attempt). Following the transitional government, the Democratic Opposition of Serbia secured the supermajority in December 2000 parliamentary elections. On 25 January 2001, Zoran Đinđić formed the cabinet and became the Prime Minister of Serbia.

2001–03: Đinđić's government

The main goal of the Đinđić's government was to reform the country exhausted of 1990s wars and to work towards joining the EU. The newly elected Yugoslav president Vojislav Koštunica, although ally of Đinđić, had much more conservative policies opposed to Đinđić's policies. Đinđić was seen as a pro-western politician and Koštunica as neutral, with aspirations to closer ties with Russia.

Although many new laws in this period were adopted and the economy stabilised with the great help from the western countries, the consequences of the bloody 1990s remained in some form. The western countries pushed the Đinđić's government to cooperate with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Their financial help was heavily conditioned on the degree of fulfilment of those demands.

12 March 2003: Assassination

In 2002, one of the main tasks of the Đinđić's government was the suppression of the organised crime. Many new laws for the organised crime were adopted, including the foundation of the Special Court for the organised crime. Many parallel structures in the country, including the Belgrade-based criminal gangs, most notably the Zemun Clan saw the great threat in government actions. Zemun Clan headquarters in Belgrade's Schiller Street, many saw as the parallel centre of the power in the country. Also, leaders of the mentioned elite police unit JSO had their connections to the Zemun Clan.

On 21 February 2003, near the Limes Hall on the Belgrade–Zagreb highway, the assassination was attempted by the Zemun Clan members. Dejan Mileković Bagzi, a truck driver who had a goal to perform the traffic accident, while the other members had to kill the Prime Minister with the rocket throwers after the car incident. However, by mere coincidence and good response from driver of the motorcade, the car accident was avoided. Milenković was arrested, but unfortunately, the plan to assassinate the Prime Minister was not proven and he was released days after. Later turned out that the police had collected the evidences of a planned assassination, but someone covered it up.

On 12 March 2003, at 12:25 Central European Time, Đinđić was fatally wounded by a gunshot while entering the Serbian government building where he was supposed to meet Foreign Minister of Sweden, Anna Lindh, and her colleague Jan O. Karlsson. The high-powered bullet with which he was shot penetrated his heart and killed him almost instantly.[1] According to the official government statement, Đinđić was not conscious and did not have a pulse upon arriving at the emergency ward.[2] His personal bodyguard, Milan Veruović, was also seriously wounded in the stomach by another shot, but eventually survived.

According to the official verdict, member of JSO Zvezdan Jovanović, fatally shot Đinđić from the window of a building approximately 180 meters away, using a 7.62mm Heckler & Koch G3 rifle.[3]

March–April 2003: Operation Sabre

Shorty after the assassination, state of emergency in Serbia was launched.[4] In full-scale police operation Sabre, 11,665 people were detained in Serbia, many criminals have been killed, including the boss of Zemun Clan Dušan Spasojević. Milorad Ulemek, the prime suspect who allegedly organized the assassination, was on the run for more than a year, and surrendered in 2004.

Trial

The Zoran Đinđić trial in newly formed Special Court for the organised crime, lasted until 2007 and was dubbed by some media as the most important trial of Serbian Justice in a century (Serbian: sudski proces veka).[5] Four members of Zemun Clan received a special status of cooperative witness. In 2006, President of the Chamber in the trial, withdrew from the case, and the other Chamber member Nata Mesarović stepped in his place.

The trial was marked with great political pressure and life threats to the Chamber members and cooperative witnesses. Also, several witnesses were murdered during the trial.

On 23 May 2007, the Special Court found Simović and eleven other men - Milorad Ulemek, Zvezdan Jovanović, Dejan Milenković, Vladimir Milisavljević, Sretko Kalinić, Ninoslav Konstantinović, Milan Jurišić, Dušan Krsmanović, Željko Tojaga, Saša Pejaković and Branislav Bezarević - guilty for the premeditated murder of Zoran Đinđić.[4] Many of them were sentenced to 40 years – maximum sentence in Serbia. However, no evidences for the political background were found.[4]

In April 2008, Carla Del Ponte, former Chief Prosecutor of two United Nations international criminal law tribunals, published a book The Hunt: Me and the War Criminals, in which she stated that Đinđić cooperated with the Hague Tribunal unconditionally in accordance to international obligations of Serbia, even though he had great resistance in national political, intelligence and defence circles.[6]

Overview

Security officer Milan Veruović, personal bodyguard of Zoran Đinđić, who was also severely injured by the sniper shot, testified on the day of the assassination, in the Emergency Center intensive care room, that there were three shots fired instead of what was believed - two shots.[7] Four months later in July 2003, he was officially interrogated for the first time.

On 21 October 2003, he gave interview in B92 radio's morning talk-show Kažiprst in which he said that: "(I) suspect (that) Đinđić was shot at by two snipers. I believe that the bullet which hit the prime minister could not, by the position of the body, have come from Admiral Geprat Street, but from the opposite direction, from No.6 Birčaninova Street"[7] and that all 9 members of the personal security of Prime Minister, who were closest to the crime scene, heard three bullets fired, of which the first hit Đinđić, the second hit Veruović, and the third hit the door frame of the government building entrance.[7] That was the first time he came publicly with the statement of the third bullet.

Eleven years following the assassination of Zoran Đinđić, seven years after final verdicts, Veruović and Vrzić have published the first edition of the book, on 5 September 2014.[8] The book is based on the vast material, from court records and transcripts of the trial to police reports and public testimonies.[8]

The authors claim that just about anything is debatable in the official version of the assassination. They claim that: "the expertise on which the official version is largely based on, is completely untenable, contrary to the laws of physics and the physical evidence and the testimony of witnesses. Many material proofs were not analysed."[8]

To discover the political background, authors returned to analysing Đinđić's political activities over a period of several months before his death.[8] They stated that: "he had become a threat to the Pax Americana in these areas"; that could be seen in his relationship with the Hague Tribunal whom he "didn't want to hand over war archives and generals", he mentioned the revision of the Dayton Agreement questioning the independence of Republika Srpska if the issue of Kosovo and Metohija is not discussed (via UN Resolution 1244).[8] In the last interview he gave on 6 March 2003, Đinđić expressed concern that his western allies "are not honest friends of Serbia and are not willing to discuss the Kosovo issue, but rather", he suspects: "under wraps working on its independence".[9] After his death, his "self-proclaimed successors" completely turned his policy in favour of western interests; and all the threats to the Pax Americana were gone.[8]

Authors of the book said that the only motive for the publication of the book is the truth about the 12 March, what led to the assassination of Đinđić, and what are the consequences of the assassination for Serbia.[8]

Content

In the book, authors are challenging the official version of the assassination of the Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić. Authors claim that indictment (and later trial verdict) is not based on the physical evidences nor eyewitness testimonies, but constructed on unsustainable expertise and carefully built network of confessions and testimonies of cooperative witnesses, of which neither of the two does not fit with undeniable facts. The authors also accused several Đinđić's then close associates in covering up the traces of their connections with the Zemun Clan, and involvement in the assassination, most notably Vladimir Beba Popović (served as Secretary of the Communications Bureau at the time), Čedomir Jovanović (served as a member of parliament and vice president of Democratic Party at the time) and other associates. The authors also indicate the motives for the political assassination in form of questions:

- What has remained of Zoran Đinđić policies after his death? Have the successors changed his policy? On whose behalf these changes were?

- Was Zoran Đinđić presented as traitor to help us believe that he was killed by patriots? The same way as he has been linked with organised crime only to be later believed that it is quite logical that criminals had killed him.

Part One of the book looks at the events which occurred on 12 March 2003 (on day of the assassination), and events which followed. Part Two examines the events which preceded and lead to the assassination in wider context. It also examines ubiquitous traces of involvement of foreign intelligence services, concretely Britain's MI6 and American Central Intelligence Agency. It has seven subparts:

- The 5 October 2000 Revolutionary Deals

- The 30 April 2001 Arrest of the Zemun Clan members in Paris

- The November 2001 Revolt of the JSO

- The Maka's Group

- The 21 February 2003 assassination attempt near Limes

- CIA in the Zemun Clan

- The political background

Critical and commercial reception

While the book gained popularity in Serbia and was published in several editions,[10] critics of the book were mixed.[11] Almost all the individuals (including officials) who gave negative critics about the book usually blatantly discredited the authors, also claiming that the Court already gave all the answers about the assassination.

Several media houses, including B92, Vreme and others reported pretty bold allegations, slandering the credibility of authors, also stating that the goal of their book was the "obstruction of judicial proceedings" and as extension of orchestrated media campaign directed against Đinđić's then close associates,[12] while protecting the political inspirators of Djindjic's assassination.[12]

Nikola Vrzić was dubbed as a spokesman of the leader of Democratic Party of Serbia Vojislav Koštunica, who had opposite policies compared to Đinđić's policies even though they were allies.[12] It is also said that the entire professional opus of Nikola Vrzić was dedicated to the propagation of the needs and interests of political and intelligence structures.[12] Milan Veruović was dubbed as a person with criminal record who, in order to avoid the criminal proceedings, sided with the Democratic Opposition of Serbia against Slobodan Milošević in late 1990s.[12]

Srđan Ćešić of the weekly news magazine Vreme accused authors of relaunching the "fiction" based conspiracy theories of the third bullet, refuted in court;[10] and other bold negative accusations on authors credibility, including the alleged changeable testimonies of Veruović he gave about the third bullet following the assassination.[10] The authors reacted to his writings in Vreme, saying that he is deceiving the readers by making many falsities based on unfounded accusations without reading the book; and called him to continue the debate with them based on arguments and facts, once he reads the book.[13]

Žarko Korać, then close associate of Đinđić, served as the Deputy Prime Minister of Serbia from 2001 until 2004 and acted as a Prime Minister from 17–18 March 2003, gave an interview in Peščanik in October 2014 about the book, stating that it is a "bad book" with the aim to challenge the official indictment, also blatantly discrediting both Vrzić and Veruović.[14] However, apart from the author's claim that there was a third bullet involved, he hasn't discuss any other claim the authors have given in the book. He had a task following the assassination to make a report about the eventual gaps in the security of Zoran Đinđić, which remained a state secret to this day.

Nata Mesarović, President of the Chamber in the trial, gave interview in Newsweek Serbia in June 2015, and answered whether she had read the book.[15] She said that she did and that she: "wondered how suddenly investigative journalist (Nikola Vrzić) appeared with all these ideas and suggestions".[15] She also added that she believes that Milan Veruović was just listed as the co-author of the book and that the verdict shows her analyses on why she hasn't believed to his testimonies, saying that: "it's not easy when you say that you did not believe those who were the first to the Prime Minister and cared about his life".[15]

See also

References

- "Serb police kill Djindjic suspects". bbc.co.uk. BBC. 28 March 2003. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Ubijen premijer Đinđić, vanredno stanje u Srbiji". blic.rs/ (in Serbian). Blic. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Police arrest suspected murderer of Serbian leader". unmikonline.org. AFP. 26 March 2003. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Twelve guilty of Djindjic murder". bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- "Sudski proces veka bez glavnog sudije". blic.rs (in Serbian). 1 September 2006. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- "Memoari Karle Del Ponte III". pescanik.net (in Serbian). 12 August 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Zoran Djindjic killed by second sniper Witness to the crime - an interview with the bodyguard". b92.net. 21 October 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Vasiljević, P. (5 October 2014). "Vrzić: Đinđić je ubijen iz Birčaninove". novosti.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Bilbija, Đ.; Ognjanović, R. (6 March 2003). "SRBIJA NIJE ŽETON ZA PLAĆANJE DUGOVA". novosti.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Ćešič, Srđan (11 September 2014). "Kako videti treći metak". vreme.com (in Serbian). Vreme. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Стевановић, Јелена (24 August 2013). Шта имају заједничко Срби и Американци (in Serbian). Политика Online. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Ćirić, Miloš; Čongradin, Snežana; Stojanović, Matja (18 March 2015). "Treći metak i politička pozadina atentata na Zorana Đinđića". b92.net (in Serbian). Antidot. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Veruović, Milan; Vrzić, Nikola (18 September 2014). "O Ćešićevom prikazu knjige koju nije pročitao". vreme.com (in Serbian). Vreme. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Nikčević, Tamara (5 October 2014). "Žarko Korać – intervju" (in Serbian). Peščanik. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Nata Mesarović: Prijatelji Đinđićevih ubica danas su uspešni ljudi". newsweek.rs (in Serbian). 24 June 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

External links

- Treći metak at goodreads.com

- Goli Zivot - Milan Veruovic, Nikola Vrzic on YouTube (in Serbian)

- INTERVJU: Milan Veruović - Treći metak otkriva pravu istinu o ubistvu Zorana Đinđića! on YouTube (in Serbian)