The Spy Who Loved Me (novel)

The Spy Who Loved Me is the ninth novel (and tenth book) in Ian Fleming's James Bond series, first published by Jonathan Cape on 16 April 1962. It is the shortest and most sexually explicit of Fleming's novels, as well as a clear departure from previous Bond novels in that the story is told in the first person by a young Canadian woman, Vivienne Michel. Bond himself does not appear until two-thirds of the way through the book. Fleming wrote a prologue to the novel giving Michel credit as a co-author.

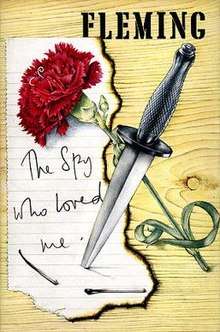

First edition cover, published by Jonathan Cape | |

| Author | Ian Fleming |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping (Jonathan Cape ed.) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 16 April 1962 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 198 |

| Preceded by | Thunderball |

| Followed by | On Her Majesty's Secret Service |

Due to the reactions by critics and fans, Fleming was not happy with the book and attempted to suppress elements of it where he could: he blocked a paperback edition in the United Kingdom and only gave permission for the title to be used when he sold the film rights to Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli, rather than any aspects of the plots. However, the character of Jaws is loosely based on one of the characters in the book and a British paperback edition was published after his death.

A heavily adapted version of The Spy Who Loved Me appeared in the Daily Express newspaper in daily comic strip format in 1967–1968. In 1977 the title was used for the tenth film in the Eon Productions series. It was the third to star Roger Moore as Bond and used no plot elements from the novel.

Plot summary

Ian Fleming, The Spy Who Loved Me, Prologue

Fleming structured the novel in three sections—"Me", "Them" and "Him" to describe the phases of the story.

- Me

Vivienne "Viv" Michel, a young Canadian woman narrates her own story, detailing her past love affairs, the first being with Derek Mallaby, who took her virginity in a field after being thrown out of a cinema in Windsor for indecent exposure. Their physical relationship ended that night, and Viv was subsequently rejected when Mallaby sent her a letter from Oxford University saying he was forcibly engaged to someone else by his parents. Viv's second love affair was with her German boss, Kurt Rainer, by whom she would eventually become pregnant. She informed Rainer and he paid for her to go to Switzerland to have an abortion, telling her that their affair was over. After the procedure, Viv returned to her native Canada and started her journey through North America, stopping to work at "The Dreamy Pines Motor Court" in the Adirondack Mountains for managers Jed and Mildred Phancey.

- Them

At the end of the vacation season, the Phanceys entrust Viv with looking after the motel for the night before the owner, Mr. Sanguinetti, can arrive to take inventory and close it up for the winter. Two mobsters, "Sluggsy" Morant and Sol "Horror" Horowitz, both of whom work for Sanguinetti, arrive and say they are there to look over the motel for insurance purposes. The two have been hired by Sanguinetti to burn down the motel so that Sanguinetti can make a profit on the insurance. The blame for the fire would fall on Viv, who was to perish in the incident. The mobsters are cruel to Viv and, when she says she does not want to dance with them, they attack her, holding her down and starting to remove her top. They are about to continue the attack with her rape when the door buzzer interrupts them.

- Him

British secret service agent James Bond appears at the door asking for a room, having had a flat tyre while passing. Bond quickly realises that Horror and Sluggsy are mobsters and that Viv is in danger. Pressuring the two men, he eventually gets the gangsters to agree to provide him a room. Bond tells Michel that he is in America in the wake of Operation Thunderball and was detailed to protect a Russian nuclear expert who defected to the West and who now lives in Toronto, as part of his quest to ferret out SPECTRE. That night Sluggsy and Horror set fire to the motel and attempt to kill Bond and Michel. A gun battle ensues and, during their escape, Horror and Sluggsy's car crashes into a lake. Bond and Michel retire to bed, but Sluggsy is still alive and makes a further attempt to kill them, before Bond shoots him.

Viv wakes to find Bond gone, leaving a note in which he promises to send her police assistance and which he concludes by telling her not to dwell too much on the ugly events through which she has just lived. As Viv finishes reading the note, a large police detachment arrives. After taking her statement, the officer in charge of the detail reiterates Bond's advice, but also warns Viv that all men involved in violent crime and espionage, regardless of which side they are on—including Bond himself—are dangerous and that Viv should avoid them. Viv reflects on this as she motors off at the end of the book, continuing her tour of America, but despite the officer's warning still devoted to the memory of the spy who loved her.

Characters and themes

Continuation Bond author Raymond Benson sees Vivienne Michel as the best realised female characterisation undertaken by Fleming, partly because the story is told in the first person narrative.[1] Academic Jeremy Black notes that Michel is the closest Fleming gets to kitchen sink realism in the Bond canon:[2] she has been a victim of life in the past,[1] but is wilful and tough, too.[3]

The other characters in the novel are given less attention and Vivienne's second lover, Kurt, is a caricature of a cruel German, who forces her to have an abortion before finishing their affair.[4] According to Black, the two thugs, Sluggsy and Horror, are "comic-book villains with comic-book names".[5] Their characters are not given the same status as other villains in Bond stories, but are second-rate professional killers, which makes them more believable in the story.[3]

As with Casino Royale, the question of morality between Bond and the villains is brought up, again by Bond, but also by the police officer involved.[1] Benson argues that this runs counter to another theme in the novel, which had also appeared in a number of other Bond books including Goldfinger: the concept of Bond as Saint George against the dragon.[1] In this Black agrees, who sees The Spy Who Loved Me as being "an account of the vulnerable under challenge, of the manipulative nature of individuals and of the possibility of being trapped by evil".[6]

Background

The Spy Who Loved Me was written in Jamaica at Fleming's Goldeneye estate in January and February 1961 and was the shortest manuscript Fleming had produced for a novel, being only 113 pages long.[7] Fleming found the book the easiest for him to write and apologised to his editor at Jonathan Cape for the ease.[8] The Spy Who Loved Me has been described by Fleming biographer Andrew Lycett as Fleming's "most sleazy and violent story ever", which may have been indicative of his state of mind at the time.[8]

Fleming borrowed from his surroundings, as he had done with all his writing up to that point, to include places he had seen. One such location was a motel in the Adirondacks in upstate New York, which Fleming would drive past on the way to Ivar Bryce's Black Hollow Farm; this became the Dreamy Pines Motel.[9] Similarly, he took incidents from his own life and used them in the novel: Vivienne Michel's seduction in a box in the Royalty Kinema,[10] Windsor, mirrors Fleming's loss of virginity in the same establishment.[11] A colleague at The Sunday Times, Robert Harling, gave his name to a printer in the story[12] while another minor character, Frank Donaldson, was named after Jack Donaldson, a friend of Fleming's wife.[13] One of Fleming's neighbours in Jamaica was Vivienne Stuart, whose first name Fleming purloined for the novel's heroine.[13]

Release and reception

... the experiment has obviously gone very much awry

— Ian Fleming, in letter to his editor[14]

The Spy Who Loved Me was published in the UK on 16 April 1962 as a hardcover edition by publishers Jonathan Cape; it was 221 pages long and cost 15 shillings.[15] Artist Richard Chopping once again undertook the cover art, and raised his fee from the 200 guineas he had charged for Thunderball, to 250 guineas.[16] The artwork included a commando knife which was borrowed from Fleming's editor, Michael Howard at Jonathan Cape.[17] The Spy Who Loved Me was published in the US by Viking Books on 11 April 1962[18] with 211 pages and costing $3.95.[19]

The reception to the novel was so bad that Fleming wrote to Michael Howard at Jonathan Cape, to explain why he wrote the book: "I had become increasingly surprised to find my thrillers, which were designed for an adult audience, being read in schools, and that young people were making a hero out of James Bond ... So it crossed my mind to write a cautionary tale about Bond, to put the record straight in the minds particularly of younger readers ... the experiment has obviously gone very much awry".[14]

Fleming subsequently requested that there should be no reprints or paperback version of the book,[20] and for the British market no paperback version appeared until after Fleming's death.[21] Because of the heightened sexual writing in the novel, it was banned in a number of countries.[22] In the US the story was also published in Stag magazine, with the title changed to Motel Nymph.[23]

Reviews

Broadly the critics did not welcome Fleming's experiment with the Bond formula. The academic Christoph Linder points out that The Spy Who Loved Me received the worst reception of all the Bond books.[6] The Daily Telegraph, for example, wrote "Oh Dear Oh Dear Oh Dear! And to think of the books Mr Fleming once wrote!"[14] while The Glasgow Herald thought Fleming was finished: "His ability to invent a plot has deserted him almost entirely and he has had to substitute for a fast-moving story the sorry misadventures of an upper-class tramp, told in dreary detail."[14] Writing in The Observer, Maurice Richardson described the tale as "a new and regrettable if not altogether unreadable variation",[24] going on to hope that "this doesn't spell the total eclipse of Bond in a blaze of cornography".[24] Richardson ended his piece by berating Fleming, asking: "why can't this cunning author write up a bit instead of down?"[24] The critic for The Times was not dismissive of Bond, who they describe as "less a person than a cult"[15] who is "ruthlessly, fashionably efficient in both love and war".[15] Rather, the critic dismisses the experiment, writing that "the novel lacks Mr. Fleming's usual careful construction and must be written off as a disappointment."[15] John Fletcher thought that it was "as if Mickey Spillane had tried to gatecrash his way into the Romantic Novelists' Association".[14]

Philip Stead, writing in The Times Literary Supplement considered the novel to be "a morbid version of that of Beauty and the Beast".[25] The review noted that once Bond arrives on the scene to find Michel threatened by the two thugs, he "solves [the problem] in his usual way. A great quantity of ammunition is expended, the zip-fastener is kept busy and the customary sexual consummation is associated with the kill."[25] Stead also considered that with the words of the police captain "Mr. Fleming seems to have summarized in this character's remarks some of the recent strictures on James Bond's activities."[25] Vernon Scannell, as critic for The Listener, considered The Spy Who Loved Me to be "as silly as it is unpleasant".[26] What aggrieved him most, however, was that "the worst thing about it is that it really is so unremittingly, so grindingly boring."[26]

The critic for Time lamented the fact that "unaccountably lacking in The Spy Who Loved Me are the High-Stake Gambling Scene, the Meal-Ordering Scene, the Torture Scene, the battleship-grey Bentley, and Blades Club."[19] The critic also bemoaned the fact that "among the shocks and disappointments 1962 still has in store ... is the discovery that the cruel, handsome, scarred face of James Bond does not turn up until more than halfway through Ian Fleming's latest book.[19] Anthony Boucher meanwhile wrote that the "author has reached an unprecedented low".[22]

Not all reviews were negative. Esther Howard wrote in The Spectator, "Surprisingly Ian Fleming's new book is a romantic one and, except for some early sex in England (rather well done, this) only just as nasty as is needed to show how absolutely thrilling it is for ... the narrator to be rescued from both death and worse – than by a he-man like James Bond. Myself, I like the Daphne du Maurier touch and prefer it this way but I doubt his real fans will."[27]

Adaptations

- Comic Strip (1967–1968)

Fleming's original novel was adapted as a daily comic strip which was published in the British Daily Express newspaper and syndicated around the world. The adaptation ran from 18 December 1967 to 3 October 1968. The adaptation was written by Jim Lawrence and illustrated by Yaroslav Horak.[28] It was the last Ian Fleming work to be adapted as a comic strip.[28] The strip was reprinted by Titan Books in The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2, published in 2011.[29]

- The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

In 1977 the title was used for the tenth film in the Eon Productions series. It was the third to star Roger Moore as British Secret Service agent Commander James Bond. Although Fleming had insisted that no film should contain anything of the plot of the novel, the steel-toothed character of Horror was included, although under the name Jaws.[30]

References

- Benson 1988, p. 129.

- Black 2005, p. 71.

- Benson 1988, p. 130.

- Black 2005, p. 73.

- Black 2005, p. 74.

- Black 2005, p. 72.

- Benson 1988, p. 21.

- Lycett 1996, p. 381.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 186.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 31.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 11.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 113.

- Lycett 1996, p. 382.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 187.

- "New Fiction". The Times. 19 April 1962. p. 15.

- Lycett 1996, p. 390.

- Lycett 1996, pp. 390–391.

- "Books – Authors". The New York Times. 29 March 1962. p. 30. (subscription required)

- "Books: Of Human Bondage". Time. 13 April 1962. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- Lycett 1996, p. 402.

- Lycett 1996, p. 446.

- Benson 1988, p. 23.

- Simpson 2002, p. 43.

- Richardson, Maurice (15 April 1962). "Crime Ration". The Observer. p. 28.

- Stead, Philip John (20 April 1962). "Bond's New Girl". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 261.

- Scannell, Vernon (3 May 1962). "New Novels". The Listener.

- Howard, Esther (1 June 1962). "The Spy Who Loved Me". The Spectator. London. p. 728.

- Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- McLusky et al. 2011, p. 285.

- Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 121.

Bibliography

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-233-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-85286-040-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-85799-783-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Paul (2002). The Rough Guide to James Bond. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-142-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Lawrence, Jim; Fleming, Ian; Horak, Yaroslav (2011). The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84856-432-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Ian Fleming Bibliography of James Bond 1st Editions

- The Spy Who Loved Me at Faded Page (Canada)