The Sick Child (Munch)

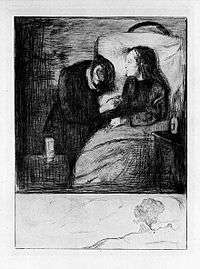

The Sick Child (Norwegian: Det syke barn) is the title given to a group of six paintings and a number of lithographs, drypoints and etchings completed by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch between 1885 and 1926. All record a moment before the death of his older sister Johanne Sophie (1862–1877) from tuberculosis at 15. Munch returned to this deeply traumatic event repeatedly in his art, over six completed oil paintings and many studies in various media, over a period of more than 40 years. In the works, Sophie is typically shown on her deathbed accompanied by a dark-haired, grieving woman assumed to be her aunt Karen; the studies often show her in a cropped head shot. In all the painted versions Sophie is sitting in a chair, obviously suffering from pain, propped by a large white pillow, looking towards an ominous curtain likely intended as a symbol of death. She is shown with a haunted expression, clutching hands with a grief-stricken older woman who seems to want to comfort her but whose head is bowed as if she cannot bear to look the younger girl in the eye.

Throughout his career, Munch often returned to and created several variants of his paintings. The Sick Child became for Munch—who nearly died from tuberculosis himself as a child—a means to record both his feelings of despair and guilt that he had been the one to survive and to confront his feelings of loss for his late sister. He became obsessive with the image, and during the decades that followed he created numerous versions in a variety of formats. The six painted works were executed over a period of more than 40 years, using a number of different models.[1]

The series has been described as "a vivid study of the ravages of a degenerative disease."[2] All of the paintings and many of the ancillary works are considered significant to Munch's oeuvre. An 1896 lithograph in black, yellow and red was sold in 2001 at Sotheby's for $250,000.[3]

The paintings

Each painting shows Sophie in profile, lying on her deathbed, and obviously having difficulty breathing, a symptom of advanced, severe tuberculosis.[4] She is propped from her waist up by a large thick white pillow which partially hides a large circular mirror hung on the wall behind her. She is covered by a heavy dark blanket. She has red hair and is shown as frail and with a sickly pallor and vacant stare.[1] She looks towards a dark and portentous full-length curtain to her left, which many art historians interpret as a symbol of death.

A dark-haired and older woman in a black dress sits by the child's bedside, holding her hand. The bond between the two is established through the joining of their hands, which are positioned at the exact center of each work. Their shared grip is typically rendered with such pathos and intensity that art historians believe that not only did the two figures share a deep emotional bond, but that they were most likely blood relations. In probability the woman is Sophie's aunt[1] Karen. Some critics have observed that the older woman is more distressed than the child; in the words of critic Patricia Donahue, "It is almost as though the child, knowing that nothing more can be done, is comforting a person who has reached the end of her endurance".[6]

The woman's head is bowed in anguish to the extent that she seems unable to look directly at Sophie. Because of this, her face is obscured and the viewer can only see the top of her head. A bottle is placed on a dressing table or locker to the left. A glass can be seen to the right on a vaguely described table.

The paintings vary in their colourisation. White especially figures in the first in the series, a representation of oblivion. Later, green and yellow figure as expressive representations of sickness, while in most works the reds represent the most dramatic and physical feature of late stage tuberculosis: coughing up blood.[1]

Style

Every piece in the series is strongly influenced by the conventions of German Expressionism, while many are heavily impressionistic in technique. The painted versions are built up from thick layers of impasto paint, and typically show strong broad vertical brush strokes. The emphasis on verticals gives the works a hazy feel and adds to their emotive power, an effect the art critic Michelle Facos described as presenting the viewer with "a scene experienced at close range but hazily, as if viewed through tears or the veil of memory".[1]

Versions

Munch was only 26 when he completed the 1885–86 painting and uncertain enough of his ability, he gave it the tentative title Study. Munch completed six paintings titled The Sick Child. Three are now in Oslo (1885–86, 1925, 1927), the others in Gothenburg (1896), Stockholm (1907), and London (1907). He created eight studies in drypoints and etching after his breakthrough in 1892 when demand for his work grew.[5]

The first version took over a year to complete. Munch found it an unhappy and frustrating experience, and the canvas was worked and reworked almost obsessively. Between 1885 and 1886 Munch painted, scrubbed out and repainted the image,[1] before finally arriving at an image he was satisfied with. He often mentioned the works in his journals and publications, and it features heavily in his "The Origin of the Frieze of Life" (Live Friesens tilblivelse). He later wrote that the 1885–86 painting was such a difficult struggle that its completion marked a major "breakthrough" in his art.[7] Munch explained: "I started as an Impressionist, but during the violent mental and vital convulsions of the Bohême period Impressionism gave me insufficient expression—I had to find an expression for what stirred my mind ... The first break with Impressionism was the Sick Child—I was looking for expression (Expressionism)."[8]

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1896. The 2nd in the series was completed while the artist was living in Paris, Konstmuseet, Gothenburg.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1896. The 2nd in the series was completed while the artist was living in Paris, Konstmuseet, Gothenburg. Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1907. 3rd in the series [9] Oil on canvas, 118 x 120 cm Thiel Gallery, Stockholm

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1907. 3rd in the series [9] Oil on canvas, 118 x 120 cm Thiel Gallery, Stockholm_-_Tate_Modern.jpg)

- Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1925. 5th in the series. Oil on canvas, 117 × 118 cm. Munch Museum, Oslo

Edvard Munch, 1927. 6th in the series

Edvard Munch, 1927. 6th in the series

The six painted versions are:[10]

- 1885–1886, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Impressionistic and dominated by strong vertical brush strokes, composed mostly from whites, greys and greens. Small areas were later over-painted.

- 1896, Konstmuseet, Gothenburg. Completed while Munch was living in Paris. Mostly greens and a richer palette, though thinner brush strokes.

- 1907, Thiel Galley, Stockholm. A commission from the Swedish financier and art collector Ernest Thiel. Thiel also commissioned from the much in demand Munch, a portrait of the banker's idol Friedrich Nietzsche,[11] whose work he later translated into Swedish.

- 1907 Tate, London. Evidence that this work was also commissioned by Thiel. For a time this painting was believed to have been executed in 1916. The work had been in the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden until 1928.

- 1925 or earlier. Munch Museum, Oslo. The painting's dating is uncertain; some art historians have proposed a completion date as early as 1916. The later date of 1925 is based on the year of its first surviving record; photograph taken in Munch's studio.[10]

- 1927 or earlier. Munch Museum, Oslo.

Painting materials

British and Norwegian scientists have investigated the painting in the Nasjonalmuseet Oslo.[12] The pigment analysis revealed an extensive palette consisting of pigments such as lead white, zinc white, artificial ultramarine, vermilion, red lake, red ochre, emerald green, chrome yellow, zinc yellow, and cobalt blue.[13]

Themes

In 1930, Munch wrote to the director of Oslo's National Gallery admitting that "As for the sick child, it was the period I think of as the Age of the Pillow. A great many painters did pictures of sick children on their pillows."[14] Munch was referring to the prevalence of tuberculosis at the time; contemporary depictions of the disease can be seen in the works of Hans Heyerdahl and Christian Krohg.

Reception

When the 1885–86 original version was first exhibited at the 1886 Autumn Exhibition in Christiania, it was jeered by spectators and drew "a veritable storm of protest and indignation" from critics dismayed at his use of impressionistic techniques, his seeming abandonment of line,[15] and the fact that the painting seemed to be unfinished. Many found it unsatisfactory that the key passage in the painting - the women's joined hands - was not well detailed, there are no lines to describe their fingers and the centerpiece essentially comprises blobs of paint. In defence Munch said, "I don't paint what I see but what I saw."[16]

The exhibition was reviewed by the critic Andreas Aubert, who wrote: "There is genius in Munch. But there is also the danger that it will go to the dogs ... For this reason, for Munch's own sake, I would wish that his Sick Child had been refused ... In its present form this 'study'(!) is merely a discarded half-rubbed-out sketch."[8]

Over 40 years later, the Nazis deemed Munch's paintings "degenerate art" and removed them from German museums. The works, which included the 1907 version of The Sick Child from the Dresden Gallery, were taken to Berlin to be auctioned. Norwegian art dealer Harald Holst Halvorsen acquired several, including The Sick Child, with the goal of returning them to Oslo. The 1907 painting was purchased by Thomas Olsen in 1939 and donated to the Tate Gallery.[7]

Legacy

On 15 February 2013, four Norwegian postage stamps were published by Posten Norge, reproducing images from Munch's art to recognise the 150th anniversary of his birth. A close-up of the child's head from one of the lithographic versions was used for the design of the 15 krone stamp.[17]

References

Notes

- Facos, 361

- Eisenman, Stephen; Crow, Thomas; Lukacher, Brian. "Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History". London: Thames & Hudson, 2007. 422. ISBN 0-5002-8650-7

- Lot 338: The Sick Child (Das Kranke Kind I). artvalue.com. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Cordulack, 23

- "Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, a drypoint". British Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Donahue, Patricia. "Nursing, the Finest Art: An Illustrated History". St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1996. 433.

- "The Sick Child, 1907". Tate Gallery, London. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Eggum, 46

- The Sick Child, 1907, Thiel Gallery. Retrieved 30 January 2020

- "The Sick Child 1907: Catalogue entry". Tate, London. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Prideaux, Sue. "Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream". Yale University Press, 2007. 231. ISBN 0-3001-2401-5

- Brian Singer, Trond Aslaksby, Biljana Topalova-Casadiego and Eva Storevik Tveit, Investigation of Materials Used by Edvard Munch, Studies in Conservation 55, 2010, pp. 274-292.

- Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, Nasjonalmuseet Oslo, ColourLex

- Bischoff, 10

- Eggum, 45

- Byatt, AS. "Edvard Munch: the ghosts of vampires and victims". The Guardian, 22 June 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Munch’s “The Scream” on a Postage Stamp

Sources

- Bischoff Ulrich. Edvard Munch: 1863–1944. Berlin: Taschen, 2000. ISBN 3-8228-5971-0

- Cordulack, Shelley Wood. Edvard Munch and the Physiology of Symbolism. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8386-3891-0

- Eggum, Arne. Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies. New York: C.N. Potter, 1984. ISBN 0-517-55617-0.

- Facos, Michelle. An Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art. Routledge, 2011. ISBN 0-4157-8072-1

External links

- The Sick Child at the Tate: Display caption; Catalogue entry; Illustrated companion

- ""Humbug" "Infantilt" "Uappetittlig"" ["Humbug" "Infantile" "Unappetizing"]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 2013-09-03.

- Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, Nasjonalmuseet Oslo, at ColourLex