The Otterbury Incident

The Otterbury Incident is a novel for children by Cecil Day-Lewis first published in the UK in 1948 with illustrations by Edward Ardizzone, and in the USA in 1949. Day-Lewis's second and final children's book, the novel is an adaptation of a French screenplay, Nous les gosses (Us Kids), that was filmed in 1941.[1]

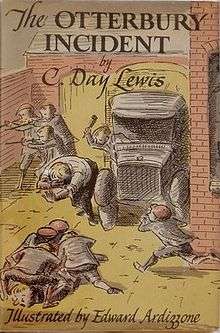

First edition | |

| Author | Cecil Day-Lewis |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Edward Ardizzone |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's novel |

| Publisher | Putnam & Company (UK) Viking Press (US) |

Publication date | 1948 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 148 pp |

Plot

The novel is set in the immediate post-World War II period in the fictional English small provincial town of Otterbury. The town was largely untouched by the war apart from one accidental hit from a mis-targeted bomb which destroyed a few buildings near the centre of the town; schoolboy Nick Yates was pulled from the ruins and his parents were killed. The bombsite is known locally as the "Incident" of the book's title, and is used as a site for war-games by two rival gangs of boys from the local King's School: Ted's Company, led by 13-year-old Edward Marshall, whose second-in-command is George, the narrator, and which includes Nick, Charlie Muswell and Young Wakeley, and the 'enemy' Toppy's Company, led by William Toppingham (also 13) and his sidekick Peter Butts, and including the ghastly Prune.

After a battle during the school lunch-hour ("dinner-interval") in which Ted's Company have been declared victorious, the boys are wildly kicking a football to each other on the way back to school when Nick accidentally kicks it through one of the school windows. After owning up, he is ordered by the headmaster – a character much feared by the boys – to pay for the damage out of his own pocket. The sum concerned amounts to nearly five pounds (a huge amount - a reasonable weekly wage for an employed adult at the time and is far beyond the means of a schoolboy). Compounding the problem, the orphaned Nick now lives with his aunt and uncle who have no children of their own; they resent the unlooked-for responsibility and do not treat him well, and he cannot face confessing to them for fear of their reaction (when he finally does, he is severely punished and his uncle decides to sell Nick's puppy).

Ted arouses a sense of collective responsibility for Nick's plight amongst the boys of both companies, in the spirit of 'One for all and all for one' from The Three Musketeers which their English teacher, Mr Richards ('Rickie' – "a decent chap, as schoolmasters go") is currently reading to them, because they were all involved in the irresponsible football-kicking. The boys resolve to raise the money between them to pay for the damage. To this end, Ted and Toppy sign the Peace of Otterbury temporarily ending hostilities between the gangs and they join together to launch Operation Glazier; over a bank holiday weekend they carry out a variety of money-making schemes such as busking (led by Charlie Muswell), shoe-shining (with some illicit spraying of dirty water via a flit gun to increase trade), window-cleaning (Kwik-Klean Co.), an acrobat troupe, and lightning sketches by Toppy's sister (Miss E Toppingham, R.A.) to raise the money.

Operation Glazier exceeds its target, but the money mysteriously disappears whilst in the charge of Ted and his grown-up sister, Rose, who looks after him. Toppy initially accuses Ted – who is ostracised by all but George and the ever-loyal Nick Yates – but then realises the real culprits are the deeply unpleasant local spiv Johnny Sharp and his seedy accomplice known as "The Wart". The boys turn detective to try to recover the money, stalking the Wart (who is much the weaker character of the two) and trying to extract a confession from him, but Johnny Sharp interrupts the proceedings, threatens the boys with a cut-throat razor, and locks them in the tower of the local church.

The boys escape and rethink their strategy to expose Sharp and the Wart; they have seen the men hanging out with a local merchant named Skinner and suspect that the missing money might be on Skinner's premises, just opposite the Incident (the boys are afraid of Skinner – "a whacking great bad-tempered thug of a man" – and avoid him as much as possible, though occasionally trespass into his yard as part of their war games). Ted and Toppy use the combat-planning skills they've developed during the games at the Incident to lead a well-planned raid on Skinner's warehouse where they uncover evidence of far more extensive criminal activities, including trading in black-market goods and production of counterfeit coinage. Skinner, Sharp, the Wart and a fourth accomplice (an 'unshaven type') return unexpectedly while Ted and Toppy are inside the warehouse. Toppy escapes but Ted is trapped and taken prisoner by Johnny Sharp.

The rest of the boys are still outside the yard, poised to attack: George is sent off to get the police while the other boys start a pitched battle to rescue Ted, in which The Wart and Skinner are overpowered and trussed up. Ted is saved thanks to Nick, who bravely attacks Sharp and is seriously injured in the process. Sharp escapes on foot, pursued by the boys, and by this time, also the police – his attempt to get away in a dinghy up the river is brought to a prompt end by Peter Butts who launches a firework at the dinghy and capsizes it.

The book ends at school assembly with the boys being simultaneously castigated for their illegal raid on Skinner's premises and their "disreputable" money-raising schemes, which are considered by the headmaster to be detrimental to the image of the school, and lauded as heroes for uncovering the criminals' operations by Inspector Brook. The headmaster relents in the light of Inspector Brook's praise and says that the school will pay for the broken window (the missing money not having been recovered). The boys promise to leave any future criminal detection to the police.

The book is written in the first person of George, a subordinate "officer" in one of the "armies" of the war games.

Reception

The novel has been commended for its style, which is a parody of serious historical writing. One critic commented that "George [the narrator] very much styles himself the official war historian, writing up the history of 'The Otterbury Incident' in the high serious language of an epoch changing event. It is the delightful first person voice of George that gives the novel its humour and charm. Sometimes poor George – who is a just a little bit on the geeky side – takes his writing responsibilities more seriously than the combatants."[2] The book was included in the UK Department of Education reading list for 1972.

References

- Benjamin Watson, English Schoolboy Stories: An Annotated Bibliography, Scarecrow Press 1992, ISBN 0-8108-2572-4

- Saliba, Chris (10 February 2011). "Review—The Otterbury Incident, by Cecil Day-Lewis". Suite.io. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

the book was added to the school reading list in 1965.