The Night Battles

The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries is a historical study of the benandanti folk custom of 16th and 17th century Friuli, Northeastern Italy. It was written by the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg, then of the University of Bologna, and first published by the company Giulio Einaudi in 1966 under the Italian title of I Benandanti: Stregoneria e culti agrari tra Cinquecento e Seicento. It was later translated into English by John and Anne Tedeschi and published by Routledge and Kegan Paul in 1983 with a new foreword written by the historian Eric Hobsbawm.

The first English-language edition of the book. | |

| Author | Carlo Ginzburg |

|---|---|

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian, English |

| Subject | Italian history History of religion |

| Publisher | Giulio Einaudi, Routledge and Kegan Paul |

Publication date | 1966 |

Published in English | 1983 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 209 |

In The Night Battles, Ginzburg examines the trial accounts of those benandante who were interrogated and tried by the Roman Inquisition, using such accounts to elicit evidence for the beliefs and practices of the benandanti. These revolved around their nocturnal visionary journeys, during which they believed that their spirits traveled out of their bodies and into the countryside, where they would do battle with malevolent witches who threatened the local crops. Ginzburg goes on to examine how the Inquisition came to believe the benandanti to be witches themselves, and ultimately persecute them out of existence.

Considering the benandanti to be "a fertility cult", Ginzburg draws parallels with similar visionary traditions found throughout the Alps and also from the Baltic, such as that of the Livonian werewolf, and also to the widespread folklore surrounding the Wild Hunt. He furthermore argues that these Late Medieval and Early Modern accounts represent surviving remnants of a pan-European, pre-Christian shamanistic belief concerning the fertility of the crops.

Academic reviews of The Night Battles were mixed. Many reviewers argued that there was insufficient evidence to indicate that the benandanti represented a pre-Christian survival. Despite such criticism, Ginzburg would later return to the theories about a shamanistic substratum for his 1989 book Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath, and it would also be adopted by historians like Éva Pócs, Gabór Klaniczay, Claude Lecouteux and Emma Wilby.

Background

In the Archepiscopal Archives of Udine, Ginzburg came across the 16th and 17th century trial records which documented the interrogation of several benandanti and other folk magicians.[1] Historian John Martin of Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas would later characterize this lucky find as the sort of "discovery most historians only dream of."[1]

Prior to Ginzburg's work, no scholars had investigated the benandanti, and those studies which had been made of Friulian folklore – by the likes of G. Marcotti, E. Fabris Bellavitis, V. Ostermann, A. Lazzarini and G. Vidossi – had all used the term "benandante" as if it had been synonymous with "witch". Ginzburg himself would note that this was not because of "neglect nor… faulty analysis", but because in the recent oral history of the region, the two terms had become essentially synonymous.[2]

English translation

The translation of The Night Battles into English was undertaken by John and Anne Tedeschi, a couple who had previously produced the English translation for Ginzburg's 1976 book The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller. In their Translator's Note to the English edition, they proclaimed that they were "very pleased" to have been given the opportunity to translate the book, opining that Ginzburg's two works "represent only a small part of the best of the new social, cultural and religious history being written today by a host of distinguished Italian scholars." The Tedeschis went on to note that in translating The Night Battles, they had decided to adopt the Italian terms benandante and benandanti (singular and plural respectively) rather than trying to translate such terms into English. As they noted, a "literal translation" of these words would have been "those who go well" or "good-doers", terms which they felt did not capture the original resonance of benandanti. They also noted that in their translation they had used the term "witch" in the broader sense to refer to both males and females, but that when the Italian text specifically mentioned strega and stregone they rendered them as "witch" and "warlock".[3]

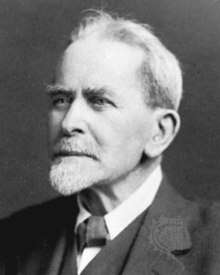

The English translation included a foreword by the prominent English historian Eric Hobsbawm (1917–2012), in which he argued that the "real interest in [Ginzburg's] extremely interesting book" lay not in its discussion of shamanistic visionary traditions, but in its study of how the Roman Catholic Church intervened in "traditional peasant practices" and warped them to fit their own ideas about witchcraft. He went on to note that The Night Battles should "fascinate and stimulate all historians of the popular mind."[4]

Synopsis

The Night Battles is divided into four chapters, preceded by a preface written by Ginzburg, in which he discusses the various scholarly approaches that have been taken to studying Early Modern witchcraft, including the rationalist interpretation that emerged in the 18th century and the Witch-cult hypothesis presented by Margaret Murray. He proceeds to offer an introduction to the benandanti, and then thanks those who have helped him in producing his study.[5]

Part I: The Night Battles

Montefalco's record of what Moduco informed him, 1580. Quoted by Ginzburg, 1983.[6]

The first part of The Night Battles deals primarily with the accounts of two benandante who were interrogated and sentenced for heresy by the Roman Inquisition between 1575 and 1582. These two figures, Paulo Gaspurotto of the village of Iassaco and Battista Moduco of the town of Cividale, first came under investigation from the priest Don Bartolomeo Sgabarizza in 1575. Although Sgabarizza later abandoned his investigations, in 1580 the case was re-opened by the Inquisitor Fra Felice da Montefalco, who interrogated both Gaspurotto and Moduco until they admitted that they had been deceived by the Devil into going on their nocturnal spirit journeys. In 1581 they were sentenced to six months imprisonment for heresy, a punishment that was later remitted.[7]

Ginzburg then looks at Gaspurotto and Moduco's claims in greater detail, noting that the benandanti constituted "a true and proper sect" who were united by having been born with a caul.[8] He proceeds to examine the trances that the benandanti went into in order to go on their nocturnal spirit journeys, debating whether these visions could have been induced by the use of special psychoactive ointments or by epilepsy, ultimately arguing that neither offer a plausible explanation in light of the historical evidence at hand.[9]

Ginzburg looks at the agricultural elements to the benandanti's battles with their satanic opponents, arguing that their clashes represent an "agricultural rite" that symbolized the forces of famine fighting the forces of plenty. He suspected that this was a survival from an "older fertility rite" that had originated in pre-Christian Europe but which had subsequently been Christianized.[10] He then goes on to examine the Early Modern accounts of aspects of popular belief across Europe that were similar to those of the benandanti. In particular he highlights the alleged cult of the goddess Diana that was recorded in late 15th century Modena and the case of the Livonian werewolf which occurred in 1692. Ginzburg ultimately argued that these scattered visionary traditions represented surviving elements of a pan-central European agrarian cult that had predated Christianization.[11]

Part II: The Processions of the Dead

In the second part of The Night Battles, Ginzburg turns his attention toward those Early Modern Alpine traditions dealing with nocturnal processions of the dead. He initially discusses the interrogation of Anna la Rossa, a self-confessed spirit medium who was brought before the Roman Inquisition in Friuli in 1582, before detailing two similar cases that took place later that year, that of Donna Aquilina and Caterina la Guercia. The latter of these women claimed that her deceased husband had been a benandante, and that he had gone on a "procession with the dead", but none of them described themselves as being benandante.[12]

Ginzburg then looks at the Canon Episcopi, a 9th-century document that denounced those women who believed that they went on nocturnal processions with the goddess Diana; the Canon's author had claimed that they were deceived by the Devil, but Ginzburg argues that it reflects a genuine folk belief of the period. He connects this account with the many other European myths surrounding the Wild Hunt or Furious Horde, noting that in those in central Europe, the name of Diana was supplanted by that of Holda or Perchta. Ginzburg then highlights the 11th-century account produced by French Bishop William of Auvergne, in which he had described a folk belief surrounding a female divinity named Abundia or Satia, who in William's opinion was a disguised devil. According to William's account, this creature travelled through houses and cellars at night, accompanied by her followers, where they would eat or drink whatever they found; Ginzburg noted parallels with the benandanti belief that witches would drink all of the water in a house.[13]

Ginzburg, 1966.[14]

Ginzburg highlights more evidence of the Wild Hunt folk motif in the Late Medieval accounts of the Dominican friar Johannes Nider. Nader related that certain women believed that they were transported to the conventicles of the goddess Herodias on the Ember Days, something which the monk attributed to the trickery of the Devil. Proceeding with his argument, Ginzburg describes an account by the chaplain Matthias von Kemnat, who recorded the persecution of a sect at Heidelberg circa 1475. According to Kemnat, this sect contained women who believed that they "travelled" during the Ember Days and cast non-fatal spells on men.[15] Ginzburg then turns his attention to a work of the early 16th century, Die Emeis, written by the Swiss preacher Johann Geiler von Kaisersberg. In this account, Geiler refers to those people who went on nocturnal visits to see Fraw Fenus (Venus), including those women who fell into a swoon on the Ember Days, and who described a visit to Heaven after they had awoken.[16]

In further search of references to processions of the dead in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Ginzburg then highlights a 1489 trial of the weaver Giuliano Verdana held in Mantua and the 1525 trial of a woman named Wyprat Musin in Burseberg, in both of which the defendant claimed to have seen a procession of dead spirits led by a female figure.[17] This is then followed by a discussion of the case of German herdsman Chonrad Stoecklin, who recounted visionary experiences in 1587 before being condemned as a witch.[18] Following on from this, Ginzburg discussed the existence of clerici vagantes who were recorded as travelling around the Swabian countryside in 1544, performing folk magic and claiming that they could conjure the Furious Horde.[19] Ginzburg then discusses the case of Diel Breull, a German sorcerer who was tried in Hesse in 1630; Breull had claimed that on a visionary journey he encountered Fraw Holt, who revealed that he was a member of her nocturnal band.[20]

Ginzburg then makes comparisons between the benandanti and the Perchtenlaufen, an Alpine ceremony in which two masked groups of peasants battled one another with sticks, one dressed to appear ugly and the other to appear beautiful.[21] Debating as to whether the traditions surrounding the processions of the dead originated in Germanic or Slavic Europe, Ginzburg then goes on to discuss the significance of the caul in benandanti belief.[22]

Part III: The Benandanti between Inquisitors and Witches

In Part III, Ginzburg comments on how uninterested the Inquisition were in the benandanti between 1575 and 1619, noting that "The benandanti were ignored as long as possible. Their 'fantasies' remained enclosed within a world of material and emotional needs which inquisitors neither understood, nor even tried to understand." He proceeds to discuss the few isolated incidents in which they did encounter and interact with the benandante during this period, opening with a discussion of the denunciation and arrest of self-professed benandanti Toffolo di Buri, a herdsman from the village of Pieris, that took place in 1583. This is followed by an exploration of the 1587 investigation into a midwife named Caterina Domenatta, who was accused of sorcery, and who admitted that both her father and dead husband had been benandante.[23] From there, Ginzburg outlines a number of depositions and records of benandanti that were produced from 1600 to 1629, arguing that towards the latter end of this period, benandanti were becoming more open in their denunciations of witches and that inquisitors were increasingly viewing them as a public nuisance rather than as witches themselves.[24]

Part IV: The Benandanti at the Sabbat

Arguments

The benandanti and the Inquisitors

In Ginzburg's analysis, the benandanti were a "fertility cult" whose members were "defenders of harvests and the fertility of fields."[25] He noted that by the time of the records of the benandanti that were produced in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the tradition was still an "actual living cult" rather than some "fossilized superstition" from preceding centuries.[26]

Ginzburg noted that with the notable exception of the cases brought against Gasparutto and Moduco by Montefalco in 1581, in the period between 1575 and 1619, no case against a benandante was brought to its conclusion. He noted that this was not down to the inefficiency of the Inquisitors, because they were effective in the repression of Lutheranism at the same time, but because they were essentially indifferent to the existence of benandanti beliefs, viewing them as little threat to orthodox Catholic belief.[27]

In his original Italian preface, Ginzburg noted that historians of Early Modern witchcraft had become "accustomed" to viewing the confessions of accused witches as being "the consequences of torture and of suggestive questioning by the judges".[28]

A pan-European fertility cult

Ginzburg argues that the benandanti fertility cult was connected to "a larger complex of traditions" that were spread "from Alsace to Hesse and from Bavaria to Switzerland", all of which revolved around "the myth of nocturnal gatherings" presided over by a goddess figure, varyingly known as Perchta, Holda, Abundia, Satia, Herodias, Venus or Diana. He also noted that "almost identical" beliefs could be found in Livonia (modern Latvia and Estonia), and that because of this geographic spread "it may not be too daring to suggest that in antiquity these beliefs may once have covered much of central Europe."[29]

Relationship to Margaret Murray's theories

In the first part of the 20th century, the English Egyptologist and anthropologist Margaret Murray (1863–1963) had published several papers and books propagating a variation of the Witch-cult hypothesis, through which she claimed that the Early Modern witch trials had been an attempt by the Christian authorities to wipe out a pre-existing, pre-Christian religion focused around the veneration of a horned god whom the Christians had demonised as the Devil. Although gaining some initial support from various historians, her theories were always controversial, coming under early criticism from experts in the Early Modern witch trials and pre-Christian religion. Eventually, her ideas came to be completely rejected within the academic historical community, although were adopted by occultists like Gerald Gardner (1884–1964) who used them as a historical basis in his creation of the contemporary Pagan religion of Wicca.[30]

Carlo Ginzburg, 1983 [1966].[31]

The definitive rejection of Murray's Witch-Cult theories among academia occurred during the 1970s, when her ideas were attacked by two British historians, Keith Thomas and Norman Cohn, who highlighted her methodological flaws.[32] At the same time, a variety of scholars across Europe and North America – such as Alan Macfarlane, Erik Midelfort, William Monter, Robert Muchembled, Gerhard Schormann, Bente Alver and Bengt Ankarloo – began to publish in-depth studies of the archival records from the witch trials, leaving no doubt that those tried for witchcraft were not practitioners of a surviving pre-Christian religion.[32]

In the original Italian preface to the book, published in 1966, Ginzburg discussed the work of Murray, claiming that although it contained "a kernel of truth", it had been "formulated in a wholly uncritical way", containing "serious defects".[31] With the complete academic rejection of Murray's theories in the 1970s, Ginzburg attempted to clarify his work's relationship to Murray's Witch-Cult theory in his "Preface to the English Edition", written in 1982. Here, he expressly stated that "Murray, in fact, asserted: (a) that witchcraft had its roots in an ancient fertility cult, and (b) that the sabbat described in the witchcraft trials referred to gatherings which had actually taken place. What my work really demonstrated, even if unintentionally, was simply the first point."[33] He proceeded to accept that although he ultimately rejected her ideas, he reiterated that there was a "kernel of truth" in Murray's thesis.[33]

Some historians have described Ginzburg's ideas as being connected to those of Murray. Hungarian historian Gábor Klaniczay asserted that "Ginzburg reformulated Murray's often fantastic and very inadequately documented thesis about the reality of the witches' Sabbath" and thus the publication of I Benandanti in 1966 "reopened the debate about the possible interconnections between witchcraft beliefs and the survival of pagan fertility cults".[34] Similarly, Romanian historian of religion Mircea Eliade asserted that while Ginzburg's presentation of the benandanti "does not substantiate Murray's entire thesis", it did represent a "well-documented case of the processus through which a popular and archaic secret cult of fertility is transformed into a merely magical, or even black-magical practice under the pressure of the Inquisition."[35] Conversely, other scholars sought to draw a clear divide between the ideas of Murray and Ginzburg. In 1975, Cohn asserted that Ginzburg's discovery had "nothing to do" with the theories put forward by Murray.[36] Echoing these views, in 1999 English historian Ronald Hutton asserted that Ginzburg's ideas regarding shamanistic fertility cults were actually "pretty much the opposite" of what Murray had posited. Hutton pointed out that Ginzburg's argument that "ancient dream-worlds, or operations on non-material planes of consciousness, helped to create a new set of fantasies at the end of the Middle Ages" differed strongly from Murray's argument that an organised religion of witches had survived from the pre-Christian era and that descriptions of witches' sabbaths were accounts of real events.[37]

Reception

Upon publication, Ginzburg's hypothesis in The Night Battles received mixed reviews.[38] Some scholars found his theories tantalizing, while others expressed far greater scepticism.[38] In ensuing decades, his work was a far greater influence on scholarship in continental Europe than in the United Kingdom or United States. This is likely because since 1970, the trend for interpreting elements of Early Modern witchcraft belief as having ancient origins proved popular among scholars operating in continental Europe, but far less so than in the Anglo-American sphere, where scholars were far more interested in understanding these witchcraft beliefs in their contemporary contexts, such as their connection to gender and class relations.[39]

Continental European scholarship

Ginzburg's interpretation of the benandanti tradition would be adopted by a variety of scholars based in continental Europe. It was supported by Eliade.[40] Although the book attracted the attention of many historians studying Early Modern witchcraft beliefs, it was largely ignored by scholars studying shamanism.[41]

Anglo-American scholarship

Most scholars in the English-speaking world could not read Italian, meaning that when I Benandanti was first published in 1966, the information which it contained remained out of the grasp of the majority of historians studying Early Modern witchcraft in the United States. In order to learn about the benandanti, these scholars therefore relied on the English-language book review produced by the witchcraft historian William Monter, who did read Italian.[42] A summary of Ginzburg's findings was subsequently published in English in the History of Religions journal by Mircea Eliade in 1975.[43] In his book, Europe's Inner Demons (1975), English historian Norman Cohn described I Benandanti as a "fascinating book". However, he proceeded to assert that there was "nothing whatsoever" in the source material to justify the idea that the benandanti were the "survival of an age-old fertility cult".[36]

In The Triumph of the Moon, his 1999 work examining the development of contemporary Pagan Witchcraft, English historian Ronald Hutton of the University of Bristol asserted that Ginzburg was "a world-class historian" and a "brilliant maverick".[44] Hutton opined that The Night Battles offered "an important and enduring contribution" to historical enquiry, but that Ginzburg's claim that the benandanti's visionary traditions were a survival from pre-Christian practices was an idea resting on "imperfect material and conceptual foundations."[45] Explaining his reasoning, Hutton remarked that "dreams do not self-evidently constitute rituals, and shared dream-imagery does not constitute a 'cult'," before noting that Ginzburg's "assumption" that "what was being dreamed about in the sixteenth century had in fact been acted out in religious ceremonies" dating to "pagan times", was entirely "an inference of his own". He thought that this approach was a "striking late application" of "the ritual theory of myth", a discredited anthropological idea associated particularly with Jane Ellen Harrison's 'Cambridge group' and Sir James Frazer.[46]

See also

- Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath

- Shaman of Oberstdorf: Chonrad Stoeckhlin and the Phantoms of the Night

- Dreamtime: Concerning the Boundary between Wilderness and Civilization

- Between the Living and the Dead: A Perspective on Witches and Seers in the Early Modern Age

- Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic

References

Footnotes

- Martin 1992, pp. 613–614.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. xxi.

- Tedeschi and Tedeschi 1983. pp. xi–xii.

- Hobsbawm 1983. pp. ix–x.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. xvii–xxii.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. 6.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 1–14.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. 15.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 16–20.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 22–26.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 27–32.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 33–39.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 40–41.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. 54.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 42–43.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 44–45.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 49–51.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 52–53.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. 55.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 56–57.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 57–58.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 58–61.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. 69–73.

- Ginzburg 1983, pp. 74–97.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. xx.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. 84.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. 71.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. xvii.

- Ginzburg 1983. pp. xx, 44.

- Simpson 1994; Sheppard 2013, pp. 166–169.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. xix .

- Hutton 1999, p. 362.

- Ginzburg 1983. p. xiii.

- Klaniczay 1990, p. 132.

- Eliade 1975, pp. 156–157.

- Cohn 1975, p. 223.

- Hutton 1999, p. 378.

- Martin 1992, p. 615.

- Hutton 2010, p. 248; Hutton 2011, p. 229.

- Eliade 1975, p. 157.

- Klaniczay 1990, p. 129.

- Hutton 1999, p. 276.

- Eliade 1975, pp. 153–158.

- Hutton 1999, p. 377.

- Hutton 1999, p. 278.

- Hutton 1999, p. 277.

Bibliography

- Cohn, Norman (1975). Europe's Inner Demons: An Enquiry Inspired by the Great Witch-Hunt. Sussex and London: Sussex University Press and Heinemann Educational Books. ISBN 978-0435821838.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eliade, Mircea (1975). "Some Observations on European Witchcraft". History of Religions. University of Chicago. 14 (3): 149–172. doi:10.1086/462721.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ginzburg, Carlo (1983) [1966]. The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. John and Anne Tedeschi (translators). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 978-0801843860.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ginzburg, Carlo (1990). Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath. Pantheon. ISBN 978-0394581637.

- Hutton, Ronald (1999). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192854490.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ronald (2010). "Writing the History of Witchcraft: A Personal View". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. London: Equinox Publishing. 12 (2): 239–262. doi:10.1558/pome.v12i2.239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ronald (2011). "Revisionism and Counter-Revisionism in Pagan History". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. London: Equinox Publishing. 13 (2): 225–256. doi:10.1558/pome.v12i2.239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klaniczay, Gábor (1990). The Uses of Supernatural Power: The Transformation of Popular Religion in Medieval and Early-Modern Europe. Susan Singerman (translator). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691073774.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, John (1992). "Journeys to the World of the Dead: The Work of Carlo Ginzburg". Journal of Social History. 25 (3): 613–626. doi:10.1353/jsh/25.3.613.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pócs, Éva (1999). Between the Living and the Dead: A Perspective on Witches and Seers in the Early Modern Age. Budapest: Central European Academic Press. ISBN 978-9639116184.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheppard, Kathleen L. (2013). The Life of Margaret Alice Murray: A Woman's Work in Archaeology. New York: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-7417-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Jacqueline (1994). "Margaret Murray: Who Believed Her and Why?". Folklore. 105: 89–96. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1994.9715877.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilby, Emma (2005). Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1845190798.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)