The Midwich Cuckoos

The Midwich Cuckoos is a 1957 science fiction novel written by the English author John Wyndham. It tells the tale of an English village in which the women become pregnant by brood parasitic aliens.

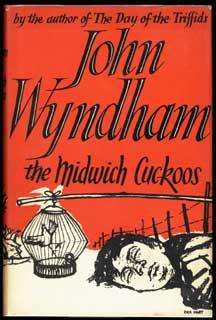

First edition | |

| Author | John Wyndham |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Dick Hart |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Michael Joseph |

Publication date | 1957 |

| Pages | 239 |

| OCLC | 20458143 |

| Preceded by | The Chrysalids |

| Followed by | The Outward Urge |

The book has been praised by many critics, including the dramatist Dan Rebellato, who called it a searching novel of moral ambiguities, and the novelist Margaret Atwood, who called the book Wyndham's chef d'oeuvre.

It has been filmed twice as Village of the Damned, with releases in 1960 and 1995. The book has been adapted for radio in 1982, 2003, and 2017.

Plot

Ambulances arrive at two traffic accidents blocking the only roads into the (fictional) British village of Midwich, Winshire. Attempting to approach the village, one ambulanceman becomes unconscious. Suspecting gas poisoning, the army is notified. They discover that a caged canary becomes unconscious upon entering the affected region, but regains consciousness when removed. Further experiments reveal the region to be a hemisphere with a diameter of 2 miles (3.2 km) around the village. Aerial photography shows an unidentifiable silvery object on the ground in the centre of the affected zone.

After one day the effect vanishes, along with the unidentified object, and the villagers wake with no apparent ill effects. Some months later they realise that every woman of child-bearing age is pregnant — even those who are single or not otherwise in relationships with men — with all indications that the pregnancies were caused by xenogenesis during the period of unconsciousness that has come to be referred to as the "Dayout".

When the 31 boys and 30 girls are born they appear normal, except for their unusual, golden eyes, light blonde hair and pale, silvery skin. These children have none of the genetic characteristics of their mothers. As they grow up, it becomes increasingly apparent that they are, at least in some respects, not human. They possess telepathic abilities, and can control others' actions. The Children (they are referred to with a capital C) have two distinct group minds — one for the boys and another for the girls. Their physical development is accelerated compared with that of humans; upon reaching the age of nine, they appear to be sixteen-year-olds.

The Children protect themselves as much as possible using a form of mind control. One young man who accidentally hits a Child in the hip while driving a car is made to drive into a wall and kill himself. A bull that chased the Children is forced into a pond to drown. The villagers form a mob and try to burn down the Midwich Grange where the Children are taught and live, but the Children make the villagers attack each other.

The Military Intelligence department learn that the same phenomenon has occurred in four other parts of the world, including an Inuit settlement in the Canadian Arctic, a small township in Australia's Northern Territory, a Mongolian village and the town of Gizhinsk in eastern Russia, northeast of Okhotsk. The Inuit killed the newborn Children, sensing they were not their own, and the Mongolians killed the Children and their mothers. The Australian babies had all died within a few weeks, suggesting that something may have gone wrong with the xenogenesis process. The Russian town was recently "accidentally" destroyed by the Soviet government, using an "atomic cannon" from a range of 50–60 miles.

The Children are aware of the threat against them, and use their power to prevent any aeroplanes from flying over the village. During an interview with a Military Intelligence officer the Children explain that to solve the problem they must be destroyed. They explain it is not possible to kill them unless the entire village is bombed, which results in civilian deaths. The Children present an ultimatum: They want to migrate to a secure location, where they can live unharmed. They demand aeroplanes from the government.

An elderly, educated Midwich resident (Gordon Zellaby) realises the Children must be killed as soon as possible. As he has only a few weeks left to live due to a heart condition, he feels an obligation to do something. He has acted as a teacher and mentor of the Children and they regard him with as much affection as they can have for any human, permitting him to approach them more closely than they allow others to. One evening, he — in effect, abusing their trust — hides a bomb in his projection equipment, while showing the Children a film about the Greek islands. Zellaby sets the timer on the bomb, killing himself and all of the Children.

Brood parasitism

The "cuckoo" in the novel's title alludes to a family of birds, of which nearly 60 species are brood parasites, laying their eggs in the nests of other birds.[1] These species are obligate brood parasites, only reproducing in this way, the best-known example being the Eurasian cuckoo. The cuckoo egg hatches earlier than the host's, and the cuckoo chick grows faster; in most cases the chick evicts the eggs or young of the host species, while encouraging the host to keep pace with its high growth rate.[2][3]

Reception

The Galaxy columnist Floyd C. Gale, reviewing the original issue in 1958, praised the novel as "a most off-trail and well-written invasion yarn."[4] Thomas M. Wagner of SFReviews.net concluded in 2004 that the novel "remains a cracking good read despite some obviously dated elements."[5] Damon Knight, however, wrote in 1967 that Wyndham's novelistic treatment "is deadly serious, and I'm sorry to say, deadly dull ... about page 90 the story begins to bog down under layers of polite restraint, sentimentality, lethargy and women's-magazine masochism, and it never lifts its head long again."[6] The writer Christina Hardyment, writing in The Times in 2008, commented that the book packed even more of a punch in an age of "genetic experimentation" than it had done in the 1950s.[7]

The dramatist Dan Rebellato, writing in The Guardian in 2010, called Wyndham probably the most successful British science fiction author since H. G. Wells, and his books so familiar that people do not study them closely. In Rebellato's view, The Midwich Cuckoos was, on rereading, "a searching novel of moral ambiguities where once I'd seen only an inventive but simple SF thriller",[8] a book that questioned the assumptions of its narrator character. It dealt, he argued, with the struggle between men and women at least as much as between people and aliens, touching on rape, abortion, childbirth and motherhood, with a subtext a great deal more subtle than the narrator's brusque story. Rebellato observed, too, that Wyndham was writing in the 1950s under the Lord Chamberlain's censorship for obscenity, so his use of "misdirection, subtext, irony and ambiguity"[8] were necessary to allow publication of his discussion of sexuality. Rebellato addresses, too, the New Wave science fiction writer Brian Aldiss's criticism of Wyndham's books as "cosy catastrophes";[9] in his view, the stories may look like that, but they are "surprisingly unheroic" and often open-ended, while underneath they are "very uncosy, persistently unsettling", asking profound questions about the limits of Western culture.[8]

The novelist Margaret Atwood, writing in Slate in 2015, commented that in her opinion, The Midwich Cuckoos was his chef d'oeuvre, selling very well, "cozy catastrophes" or not, though she observed that "one might as well call World War II—of which Wyndham was a veteran—a "cozy" war because not everyone died in it." She noted, too, that just like the children in The Chrysalids, the cuckoo children use their special abilities to help each other; and that Wyndham never made up his mind on the moral question of whether it would be a good thing to know exactly what other people were thinking.[10]

Cancelled sequel

Wyndham began work on a sequel novel, Midwich Main, which he abandoned after only a few chapters.[11]

Adaptations

Films

- The novel was filmed as Village of the Damned in 1960, with a script that was fairly faithful to the book. A sequel, Children of the Damned, followed soon afterwards.

- A Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer remake to have begun filming during 1981 was cancelled. Christopher Wood was writing the script for producer Lawrence P. Bachmann when the Writers Guild of America went on strike early that year for three months.[12][13]

- The 1994 Thai movie Kawao Thi Bang Phleng (Blackbirds at Bangpleng) is a localised version of the story. It was based on a 1989 novel by the Thai writer and politician, Kukrit Pramoj, that was clearly based on unattributed major borrowings from Wyndham's book.[14] The Thai version has differences due to the confrontation between the alien intelligences and Buddhist philosophy.[15]

- A remake of the 1960 movie was made in 1995 by John Carpenter and set in Midwich, California; it featured Christopher Reeve in his last movie role before he was paralysed, and included Kirstie Alley as a government official, a character not present in the original novel.

Radio

| Character | 1982 | 2003 |

|---|---|---|

| Bernard Westcott | Charles Kay | |

| Richard Gayford | William Gaunt | Bill Nighy |

| Janet Gayford | Rosalynd Adams | Sarah Parish |

| Gordon Zellaby | Manning Wilson | Clive Merrison |

| Angela Zellaby | Pauline Yates | Mariella Brown |

| Ferelleyn Zellaby | Jenny Quayle | Katherine Tozer |

| Alan Hughes | Gordon Dulieu | Nicholas R. Bailey |

| William | Casey O'Brien |

The novel was adapted by William Ingram in three 30-minute episodes for the BBC World Service, first broadcast between 9 and 23 December 1982. It was directed by Gordon House, with music by Roger Limb of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. It is regularly repeated on BBC Radio 4 Extra. An adaptation by Dan Rebellato in two 60-minute episodes for BBC Radio 4 was broadcast first between 30 November and 7 December 2003. It was directed by Polly Thomas, with music by Chris Madin. A CD version of this set was released by BBC Audiobooks in 2007. A new radio adaptation by Graeae Theatre Company was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 31 December 2017 and 7 January 2018.[16]

See also

- Children of the Damned, sequel to the 1960 film

References

- Payne R.B. (1997) "Family Cuculidae (Cuckoos)", pp. 508–545 in del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J (eds) (1997). Handbook of the Birds of the World Volume 4; Sandgrouse to Cuckoos Lynx Edicions: Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-22-9

- Adams, Stephen (4 January 2009). "Cuckoo chicks dupe foster parents from the moment they hatch". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

Cuckoo chicks start to mimic the cries that their foster parents' young make from the moment they hatch, a scientist has proved.

- Biology (4th edition) NA Campbell, p. 117 'Fixed Action Patterns' (Benjamin Cummings NY, 1996) ISBN 0-8053-1957-3

- Gale, Floyd C. (October 1958). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. p. 130.

- Wagner, Thomas M. (2004). "The Midwich Cuckoos". SF Reviews.net.

- Knight, Damon (1967). In Search of Wonder. Chicago: Advent. ISBN 0-911682-31-7.

- Hardyment, Christina (27 June 2008). "The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham and Nostromo by Joseph Conrad". The Times. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Rebellato, Dan (20 December 2010). "John Wyndham: The unread bestseller". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Aldiss, Brian W. (1973). Billion year spree: the history of science fiction. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-297-76555-4.

- Atwood, Margaret (8 September 2015). "Chocky, the Kindly Body Snatcher". Slate. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- "Vivisection": Schoolboy "John Wyndham's" FirstPublication? by David Ketterer, Science Fiction Studies #78, Volume 26, Part 2, July 1999. Retrieved February 26, 2015

- "Movie is Cuckoo". Windsor Star. 9 April 1981. p. 29.

- "Future Projects". Film Bulletin. Philadelphia: Wax Publications. 49: 20. July 1981.

- Movie review Archived December 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine at You Call Yourself a Scientist, retrieved on 2007-03-02.

- "Cuckoos at Bangpleng (1994)". And You Call Yourself a Scientist!. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Graeae's Midwich Cuckoos