The Maid's Metamorphosis

The Maid's Metamorphosis is a late Elizabethan stage play, a pastoral first published in 1600. The play, "a comedy of considerable merit,"[1] was published anonymously, and its authorship has been a long-standing point of dispute among scholars.

Date, performance, publication

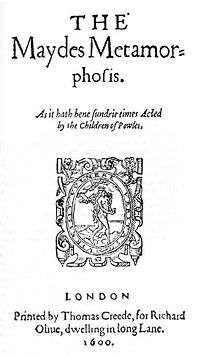

The Maid's Metamorphosis was entered into the Stationers' Register on 24 July 1600, and published later that year in a quarto printed by Thomas Creede for the bookseller Richard Olive. The title page of the first edition states that the play was acted by the Children of Paul's, one of the companies of boy actors popular at the time.[2] That company resumed dramatic performances in 1599, and the play itself refers to a leap year and a year of drought, which was true only of 1600 in the relevant period — indicating that the play was performed in that year.

Authorship

The earliest attribution of authorship was on Edward Archer's play list of 1656, which assigned the play to John Lyly. The play is written in rhymed couplets, a rather dated style for 1600; and it bears obvious resemblances to Lyly's type of drama. Yet 1600 is very late, perhaps too late, for a play by Lyly; modern critics have suggested that Archer may have confused this play with Lyly's Love's Metamorphosis. Individual scholars have discussed Lyly, John Day, Samuel Daniel, and George Peele as possible authors, though no conclusive argument has been made and no consensus has evolved in favor of any single candidate.[3] "Anonymous imitator of Lyly" may be the most accurate assignment of authorship that can be made, based on the available evidence.

Sources and influences

The author of The Maid's Metamorphosis "borrowed incidents, characters, speeches, words, phrases and rhymes" from Arthur Golding's 1567 English translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses.[4] The play also shows the influence of Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene (1590, 1596).

The play has been noted for its abundant music[5] and its use of fairies, and for a possible influence on John Fletcher's pastoral tragicomedy The Faithful Shepherdess (c. 1608).

An occasional play?

Several commentators (William J. Lawrence, Harold N. Hillebrand, Peter Saccio)[6] have argued that The Maid's Metamorphosis was an "occasional play," meaning that it was composed for a specific occasion — in this case a noble wedding, most likely the wedding of Henry Somerset, Lord Herbert (later Earl and Marquess of Worcester) and Anne Russell, which occurred on 16 June 1600.

Synopsis

The play's opening scene immediately places the audience in the realm of legend and fairy tale. The heroine, Eurymine, is accompanied into the forest by two courtiers. Their conversation reveals that the courtiers have been ordered to murder her. The local Duke, Telemachus, is incensed at his son Ascanio's devotion to the low-born Eurymine and his refusal of all the advantageous matches the father has tried to arrange. Telemachus had decided on the radical solution to the problem. The courtiers, however, take pity on Eurymine's youth, beauty, and innocence; they allow her to escape into the forest, if she agrees never to return to Telemachus's domain. They plan to fool their lord with the heart of a young goat and Eurymine's bloodstained veil.

In the forest, Eurymine meets a shepherd, Gemulo, and a forester, Silvio, both of whom are smitten with her and compete for her favors. Eurymine occupies a cottage supplied by Silvio, and maintains herself by herding some of Gemulo's sheep. Ascanio, accompanied by his fool Joculo, is meanwhile searching for Eurymine; tired and frustrated, Ascanio pauses to nap beneath a tree. As he sleeps, the goddesses Juno and Iris appear. Juno is irritated with Venus's popularity among the gods, and is determined to frustrate Venus by confounding lovers — like the handy Ascanio and Eurymine. Iris summons Somnus from his cave; Somnus and his son Morpheus provide Acanio with a deceptive dream, which sends him searching for Eurymine in the wrong direction. A comedy scene that follows provides for an appearance of singing and dancing fairies, and for the type of bawdy humor typical of Elizabethan drama.

Apollo, accompanied by the Charites (Graces), is mourning the death of Hyacinth — but he is distracted when he sees Eurymine and falls in love with her. Apollo pursues her, though Eurymine, loyal to Ascanio, spurns his advances. Questioning his claimed status as a god, she challenges him to prove his deity by transforming her into a boy — and Apollo obliges.

Joculo and other comic characters have an encounter with Aramanthus, a wise hermit (a figure common in pastorals) who can foretell the future and reveal hidden things. Ascanio and Joculo have an echo scene, in which the echo seems to supply commentary and guidance on their situation. (This is another common feature of the pastoral form, and seen in other plays of the era, like John Day's Law Tricks, Jonson's Cynthia's Revels, Peele's The Old Wives' Tale, and Webster's The Duchess of Malfi.) Ascanio meets Aramanthus, and learns that Eurymine has been transformed into a boy. Eurymine, meanwhile, is dealing with Silvio and Gemulo, trying to convince them that she is her own brother. Ascanio and the transformed Eurymine finally meet, and have a long conversation about their predicament. Aramanthus advises the couple to appeal to Apollo for mercy. With the aid of the Graces, the appeal is successful, and Eurymine is restored to her natural gender. Aramanthus, once prince of Lesbos, turns out to be Eurymine's father, making her of royal blood and a suitable match for Ascanio. News arrives that Telemachus has repented of his rash action in ordering Eurymine's death; happy ending.

Notes

- Schelling, Vol. 1, p. 151.

- Chambers, Vol. 2, p. 20, Vol. 4, p. 29.

- Logan and Smith, pp. 305–6.

- Logan and Smith, p. 307.

- Logan and Smith, pp. 307–8.

- Logan and Smith, p. 306.

References

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Golding, S. R. "The Authorship of The Maid's Metamorphosis," Review of English Studies Vol. 2 No. 7 (July 1926), pp. 270–9.

- Hillebrand, Harold Newcomb. The Child Actors: A Chapter in Elizabethan Stage History. 1926; reprinted New York, Russell & Russell, 1964.

- Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The New Intellectuals: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1977.

- Schelling, Felix Emmanuel. Elizabethan Drama 1558–1642. 2 Volumes, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1908.

- Tilley, M. P. "The Maid's Metamorphosis and Ovid's Metamorphoses," Modern Language Notes Vol. 46 No. 3 (March 1931), pp. 139–43.