John Lyly

John Lyly (Lilly or Lylie; /ˈlɪli/; c. 1553 or 1554 – November 1606) was an English writer, poet, dramatist, and courtier, best known during his lifetime for his books Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578) and Euphues and His England (1580), and perhaps best remembered now for his plays. Lyly's mannered literary style, originating in his first books, is known as euphuism.

John Lyly | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1553 Kent, England |

| Died | 1606 (aged 52–53) |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, dramatist, and courtier |

| Nationality | English |

| Notable works | Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit |

| Relatives | Peter Lyly and Jane Burgh |

Biography

John Lyly was born in Kent, England, in 1553/1554, to Peter Lyly (d. 1569) and his wife, Jane Burgh (or Brough), of Burgh Hall in the North Riding of Yorkshire. The first of eight children, he was probably born in Canterbury, where his father was the Registrar for the Archbishop Matthew Parker and where the births of his siblings are recorded between 1562 and 1568. His grandfather was William Lily, the grammarian.[1]

According to Anthony Wood, at the age of 16 Lyly became a student at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he earned his bachelor's degree in 1573 and his master's two years later. In 1574 he applied to Lord Burghley for the Queen's letters to admit him as fellow at Magdalen College, but the fellowship was not granted, and Lyly subsequently left the university. He complains about a sentence of rustication apparently passed on him at some time, in his address to the gentlemen scholars of Oxford affixed to the second edition of the first part of Euphues, but nothing more is known about either its date or its cause. Wood said that Lyly never took kindly to the proper studies of the university. "For so it was that his genius being naturally bent to the pleasant paths of poetry (as if Apollo had given to him a wreath of his own bays without snatching or struggling) did in a manner neglect academical studies, yet not so much but that he took the degrees in arts, that of master being compleated 1575."[2]

After he left Oxford, where he had the reputation of "a noted wit", Lyly seems to have attached himself to Lord Burghley. "This noble man", he writes in the Glasse for Europe, in the second part of Euphues (1580), "I found so ready being but a straunger to do me good, that neyther I ought to forget him, neyther cease to pray for him, that as he hath the wisdom of Nestor, so he may have the age, that having the policies of Ulysses he may have his honor, worthy to lyve long, by whom so many lyve in quiet, and not unworthy to be advaunced by whose care so many have been preferred." Lyly became the private secretary of Burghley's son-in-law Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, himself a playwright to whom the second part of Euphues is dedicated, and who seems to have acted as patron to most of Lyly's literary associates when they left Oxford for London.[3] Starting in 1580, Lyly received control over the Blackfriars Theatre having his plays performed by the Children of Paul’s in the presence of the Queen.

Two years later a letter from Lyly to the treasurer, dated July 1582, protests against an accusation of dishonesty which had brought him into trouble with his friend and patron, Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, and demands a personal interview in order to clear his name. However, neither from Burghley nor from Queen Elizabeth I did Lyly ever receive any substantial patronage. He began his literary career by the composition of Euphues, or the Anatomy of Wit, which was licensed to Gabriel Cawood in December 1578 and published in the spring of 1579. In the same year he was incorporated M.A. at the University of Cambridge,[4] and possibly saw his hopes of court advancement dashed by the appointment in July of Edmund Tylney to the office of Master of the Revels, a post at which he had been aiming. Euphues and his England appeared in 1580, and, like the first part of the book, won immediate popularity.

For a time Lyly was the most successful and fashionable of English writers, hailed as the author of "a new English", as a "raffineur de l'Anglois"; and, as Edward Blount, the editor of his plays, wrote in 1632, "that beautie in court which could not parley Euphuism was as little regarded as she which nowe there speakes not French". After the publication of Euphues Lyly seems to have entirely deserted the novel form, which was much imitated (e.g., by Barnabe Rich in his Second Tome of the Travels and Adventures of Don Simonides, 1584), and to have thrown himself almost exclusively into play-writing, probably still with a view to the mastership of revels. His Campaspe and Sapho were produced at Court in 1582,[5] perhaps through the earl of Oxford's station as Lord High Chamberlain. In total, probably eight Lyly plays were acted before the queen by the Children of the Chapel and especially by the Children of Paul's between the years 1584 and 1591, one or two of them being repeated before a popular audience at the Blackfriars Theatre. Their brisk lively dialogue, classical colour and frequent allusions to persons and events of the day maintained that popularity with the court which Euphues had won.

Lyly sat in parliament as a member for Hindon in Wiltshire in 1580, for Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire in 1593, for Appleby in Westmorland in 1597 and for Aylesbury a second time in 1601. In 1589 Lyly published a tract in the Martin Marprelate controversy, called Pappe with an hatchet, alias a figge for my Godsonne; Or Crack me this nut; Or a Countrie Cuffe, etc. Though published anonymously, the evidence for his authorship of the tract may be found in Gabriel Harvey's Pierce's Supererogation (written November 1589, published 1593), in Nashe's Have with You to Saffron-Walden (1596), and in various allusions in Lyly's own plays.[6]

About the same time he probably made his first petition to Queen Elizabeth. The two petitions, transcripts of which are extant among the Harleian manuscripts, are undated, but in the first of them he speaks of having been ten years hanging about the court in hope of preferment, and in the second he extends the period to thirteen years. It may be conjectured with great probability that the ten years date from 1579, when Tylney was appointed Master of the Revels with a tacit understanding that Lyly was to have the next reversion of the post. "I was entertained your Majestie's servaunt by your own gratious favor", he says, "strengthened with condicions that I should ayme all my courses at the Revells (I dare not say with a promise, but with a hopeful Item to the Revercion) for which these ten yeres I have attended with an unwearyed patience". But in 1589 or 1590 the mastership of the revels was as far off as ever—Tylney in fact held the post for thirty-one years.

In the second petition of 1593, Lyly wrote "Thirteen yeres your highnes servant but yet nothing. Twenty friends that though they saye they will be sure, I finde them sure to be slowe. A thousand hopes, but all nothing; a hundred promises but yet nothing. Thus casting up the inventory of my friends, hopes, promises and tymes, the summa totalis amounteth to just nothing". What may have been Lyly's subsequent fortunes at court are unknown. Blount says vaguely that Elizabeth "graced and rewarded" him, but of this there is no other evidence. After 1590 his works steadily declined in influence and reputation; he died poor and neglected in the early part of the reign of James I. At the end of his life, he became a Parliament member for Queen Elizabeth’s court, serving on a committee about the wine abuse reformation in 1598. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It are seen to have drawn influence from Lyly’s work. In November 1606, Lyly died from disease. He was buried in London at St Bartholomew-the-Less on 20 November 1606. He was married, and he had two sons and a daughter.

Although Euphues was Lyly's most popular and influential work in the Elizabethan period, his plays are now admired for their flexible use of dramatic prose and the elegant patterning of their construction.[7]

The proverb "All is fair in love and war" has been attributed to Lyly's Euphues.[8][9]

Comedies

In 1632 Blount published Six Court Comedies, the first printed collection of Lyly's plays. They appear in the text in the following order; the parenthetical date indicates the year they appeared separately in quarto form:

- Endymion (1591)

- Campaspe (1584)

- Sapho and Phao (1584)

- Gallathea (1592)

- Midas (1592)

- Mother Bombie (1594)

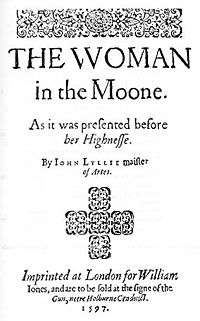

Lyly's other plays include Love's Metamorphosis (though printed in 1601, possibly Lyly's earliest play—the surviving version is likely a revision of the original), and The Woman in the Moon, first printed in 1597. Of these, all but the last are in prose. A Warning for Faire Women (1599) and The Maid's Metamorphosis (1600) have been attributed to Lyly, but on altogether insufficient grounds.

The first editions of all these plays were issued between 1584 and 1601, and the majority of them between 1584 and 1592, in what were Lyly's most successful and popular years. His importance as a dramatist has been very differently estimated. Lyly's dialogue is still a long way removed from the dialogue of Shakespeare. But at the same time it is a great advance in rapidity and resource upon anything which had gone before it; it represents an important step in English dramatic art. His nimbleness, and the wit which struggles with his pedantry, found their full development in the dialogue of Twelfth Night and Much Ado about Nothing, just as "Marlowe's mighty line" led up to and was eclipsed by the majesty and music of Shakespearean passion.

One or two of the songs introduced into his plays are justly famous and show a real lyrical gift. Nor in estimating his dramatic position and his effect upon his time must it be forgotten that his classical and mythological plots, flavourless and dull as they would be to a modern audience, were charged with interest to those courtly hearers who saw in Midas Philip II, Elizabeth in Cynthia and perhaps Leicester's unwelcome marriage with Lady Sheffield in the love affair between Endymion and Tellus which brings the former under Cynthia's displeasure. As a matter of fact his reputation and popularity as a playwright were considerable. Harvey dreaded lest Lyly should make a play upon their quarrel; Francis Meres, as is well known, places him among "the best for comedy"; and Ben Jonson names him among those foremost rivals who were "outshone" and outsung by Shakespeare.

Lyly must also be considered and remembered as a primary influence on the plays of William Shakespeare, and in particular the romantic comedies. Love's Metamorphosis is a large influence on Love's Labour's Lost, and Gallathea is a major source for A Midsummer Night's Dream. In 2007, Primavera Productions in London staged a reading of Gallathea, directed by Tom Littler, consciously linking it to Shakespeare's plays. They also claim an influence on Twelfth Night and As You Like It.

In addition to the plays, Lyly also composed at least one "entertainment" (a show that combined elements of masque and drama) for Queen Elizabeth; The Entertainment at Chiswick was staged on 28 and 29 July 1602. Lyly has been suggested as the author of several other royal entertainments of the 1590s, most notably The Entertainment at Mitcham performed on 13 September 1598.[10]

See Lyly's Complete Works, ed. R. Warwick Bond (3 vols., 1902); Euphues, from early editions, by Edward Arber (1868); AW Ward, English Dramatic Literature, i. 151; JP Collier, History of Dramatic Poetry, iii. 172; "John Lilly and Shakespeare", by C. C. Hense in the Jahrbuch der deutschen Shakesp. Gesellschaft, vols. vii and viii (1872, 1873); F. W. Fairholt, Dramatic Works of John Lilly (2 vols.) More recently, all of the comedies have been edited in individual volumes as a part of the Revels Plays series.

References

- Hunter, G. K. (2004). "Lyly, John (1554–1606)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- Wood, Anthony. Athenae Oxonienses:An exact history of all the writers and bishops who have had their education in the University of Oxford. To which are added the Fasti, or Annals of the said University. London (1813) 1:676.

- Dover Wilson, John. John Lyly, Macmillan and Bowes, Cambridge, 1905.

- "Lilly, John (LLY579J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- The Complete Works of John Lyly. R. W. Bond, 3 Vols. Clarendon Press. ii. p. 230.

- See Frederick William Fairholt's Dramatic Works of John Lilly, i. 20.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6th Edition. Edited by Margaret Drabble, Oxford University Press, 2000 p. 618

- Manser, M, and George Latimer Apperson. Wordsworth Dictionary of Proverbs. p. 355. 2006.

- Richard Alan Krieger. Civilization's Quotations: Life's Ideal. p. 49. 2002.

- Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The Predecessors of Shakespeare: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1973; pp. 137-8.

Sources

- Hunter, G. K. (1962). John Lyly: The Humanist as Courtier (376 pp). Harvard University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Lyly. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Lyly |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: John Lyly |