The Knickerbocker

The Knickerbocker, or New-York Monthly Magazine, was a literary magazine of New York City, founded by Charles Fenno Hoffman in 1833, and published until 1865. Its long-term editor and publisher was Lewis Gaylord Clark, whose "Editor's Table" column was a staple of the magazine.

| |

| Editor and publisher | Lewis Gaylord Clark |

|---|---|

| Staff writers | Washington Irving, Francis Parkman, James Russell Lowell |

| Categories | Literary magazine |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Founder | Charles Fenno Hoffman |

| Year founded | 1833 |

| Final issue | October 1865 |

| Country | The United States |

| Based in | New York City |

| Language | English |

The circle of writers who contributed to the magazine and populated its cultural milieu are often known as the "Knickerbocker writers" or the "Knickerbocker Group". The group included such authors as William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell and many others.[1]

The Knickerbocker was devoted to the fine arts in particular with occasional news, editorials and a few full-length biographical sketches.[2] The magazine was one of the earliest literary vehicles for communication about the United States' "vanishing wilderness." As such, The Knickerbocker may be considered one of the earliest proto-environmental magazines in the United States.[3]

History

Charles Fenno Hoffman was the founding editor of The Knickerbocker in 1833, though he helmed only three issues.[4] Hoffman turned the magazine over to Timothy Flint, who changed the original name The Knickerbacker to The Knickerbocker.[5] Flint then sold the magazine to Lewis Gaylord Clark, who bought it in April 1834 and served as editor until 1861.[6] By 1840, The Knickerbocker was the most influential literary publication of its time.[7] The year before, Washington Irving had reluctantly joined the staff at a salary of $2,000 a year and would stay on staff until 1841.[8] Irving disliked magazine work, specifically because of its monthly deadlines and space constraints. However, in his "Geoffrey Crayon" persona, he justified his choice in his debut issue: "I am tired... of writing volumes... there is too much preparation, arrangement, and parade... I have thought, therefore, of securing to myself a snug corner in some periodical work, where I might, as it were, loll at my ease in my elbow chair."[9]

The circle of writers who contributed to the magazine and populated its cultural milieu are often known as the "Knickerbocker writers" or the "Knickerbocker Group". The group included such authors as Washington Irving, William Cullen Bryant, James Kirke Paulding, Gulian Crommelin Verplanck, Fitz-Greene Halleck, Joseph Rodman Drake, Robert Charles Sands, Lydia M. Child, Nathaniel Parker Willis, and Epes Sargent.[10] Other writers associated with the group include Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell, Bayard Taylor, George William Curtis, Richard Henry Stoddard, Elizabeth Clementine Stedman, John Greenleaf Whittier, Horace Greeley, James Fenimore Cooper, Fitz Hugh Ludlow and Frederick Swartwout Cozzens. The Knickerbocker was one of the earliest publications of its type to pay its contributing writers.[1]

Morris Phillips (1834–1904), for a short period beginning in 1862, owned and edited the magazine. He later had been associated with the poet, Nathaniel Parker Willis (1806–1867), as associate editor of the New York Home Journal from September 1854, until Willis' death, then became chief editor and sole proprietor. In American, Phillips became known as "the father of society news."[11]

Name

The magazine was published under various titles, including:

- The Knickerbacker: or, New-York monthly magazine, from January through June 1833

- The Knickerbocker: or, New-York monthly magazine, from 1833 through 1862

- The Knickerbocker monthly: a national magazine, from 1863 through February 1864

- The American monthly knickerbocker, from March through December 1864

- The American monthly, from January through June 1865

- The Fœderal American monthly, from July through October 1865

At the time, "Knickerbocker" was a term for Manhattan's aristocracy.[12]

Knickerbocker was also an imaginary personage created by Washington Irving to promote his new book at the time, A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty. The work was a satire of both history books and the politics of the time. Irving published the work in 1809 under the pseudonym "Diedrich Knickerbocker." Prior to the release of his book though, Irving placed a series of missing person adverts in New York newspapers concerning Diedrich Knickerbocker, convincing the public that he was a legitimate historian. However, though people soon realized it was a hoax, Diedrich Knickerbocker became a much-loved character and legend for those of the city of New York.[13] He is also the namesake of the New York basketball team, The Knicks.[14]

Knickerbacker Magazine was started in January 1833 with its first issue containing a supposed conversation with Diedrich Knickerbocker. In the interview he “readily forgave the liberty taken with his name in consideration of our having restored it to its ancient spelling.” This refers to the change from Knickerbocker to Knickerbacker. However, the second issue was published with the title changed to Knickerbocker including another conversation with Diedrich Knickerbocker in which he says "I wish thee to restore my name to its original spelling as it stands in my celebrated History; so as fortune has given immortal glory to what some would consider a discreditable mistake I will even take it as it came and add the 'O' to the end of time."[15][16]

Content

The Knickerbocker was devoted to the fine arts in particular with occasional news and editorials. Full-length biographical sketches were also printed on such artists as Gilbert Stuart, Hiram Powers, Horatio Greenough, and Frederick Styles Agate.[2]

According to environmental historian, Roderick Nash, The Knickerbocker was one of the earliest literary vehicles for communication about the United States' "vanishing wilderness", including serialized articles by Thomas Cole and Francis Parkman, Jr.[3] As such, The Knickerbocker may be considered one of the earliest proto-environmental magazines in the United States. The Knickerbocker printed the earliest-known reference to the joke "Why did the chicken cross the road?"[17]

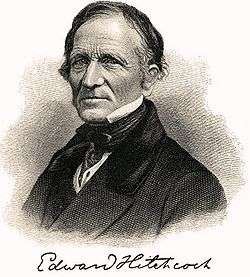

In the early 1800s, the Reverend Edward Hitchcock came across a set of what appeared to him to be giant bird tracks. These later turned out to be reptile tracks, however they nonetheless inspired him to write a poem entitled "The Sandstone Bird" involving the reanimation of a great sandstone bird by a female mystic. Later published in The Knickerbocker by Hitchcock, under the pseudonym Poetaster, this is widely believed to have been the first ichnological poem.[18]

Environmental impact

Eric Kaufman, a professor of politics commented in his paper on "American Naturalistic Nationalism" that the "naturalistic aesthetic first took root among writers in New England and New York. These intellectuals, connected by New York literary periodicals like Knickerbocker Magazine ... responded in several ways to the new naturalistic sensibility" the influence of which can be seen in many of their published works.[19]

Some famous works first published in The Knickerbocker that have influenced environmental thought include:

- The Oregon Trail, by Francis Parkman – An 1846 story of exploring the West published in 21 installments. It portrays heroic frontiersmen, struggling immigrants, and savage Native Americans. Though it is a romantic work, Parkman does not shy from the violence of the frontier, providing his audience a more realistic view of the frontier than some of his contemporaries. However, he does place emphasis on the beauty of the conquered nature over the wild.[20]

- "Scalp-Hunter," by Francis Parkman - A short story of 1845, chronicling the young Parkman's experiences in the American wilderness. The story contains frenzied hunting scenes, dangerous rock climbing and his daring ascent of a steep, crumbling ravine. The story romanticized nature, transforming harrowing experiences into wilderness adventures.[20]

- "Hints on Human Nature," by One of the People (anonymous) – December 1845 piece that compared humans with animals. It suggested that "man shares many of his intellectual and social capabilities with the lower animals. the beaver also laid up stores, the ants also established communities and governments. It was, furthermore the nature of all animals to love, hate, sorrow and rejoice. There were differences to be sure. If dogs and men alike stole, dogs did not pray to their Maker nor take his name in vain since man did both, it was fair to concede that he possessed a conscience...and the general anti-intellectualism of the piece was reflected in the remark that little could be learned about human nature from books or schools or even colleges." [21]

- Wolfert's Roost, by Washington Irving - A collection of short stories and essays, reprinted in a single volume in 1855, covering a variety of topics including: man's relationship with the land, man's relationship with man and the natural society. This work is the result of Irving's travels and research across the country and his portrayal of the beautiful nature he saw.[13] It has been said however, that this work is rather simplistic and fails to provide any true analysis of the environment.[13]

- "Prometheus," by James Russell Lowell, among the first American poets to rival the popularity of British poets.[22] This poem "proclaims the perfectibility of the human and the supremacy of Beauty" and thus reveals a Transcendentalist influence. The relative simplicity and fluidity of his writing style appealed to families as well as professionals.[23] The work provided readers with a contemporary view of nature through the lens of a classical text.

- "Sicilian Scenery and Antiquities," by Thomas Cole – A sketch of an Italian rural landscape where Cole vacationed. This article, published in 1844, presents the Sicilian landscape through a painter's eyes and is in a way an explanation of his painting on the same subject. It is a romantic portrayal of nature with hints of human influence that showed readers the beauty of the natural landscape, but also emphasizes the inextricably intertwined past and futures of man and nature.[24]

- "Mocha Dick: The White Whale of the Pacific," by Jeremiah Reynolds – The inspiration for Melville's most famous creation, Moby Dick which recounted the capture of a giant white sperm whale that had become infamous among whalers for its violent attacks on ships and their crews. The meaning of the name itself is quite simple: the whale was often sighted in the vicinity of the island of Mocha, and "Dick" was merely a generic name like "Jack" or "Tom." [25]

Further reading

- Meservey, Anne Farmer. 1978. "The Role of Art in American Life: Critics' Views on Native Art and Literature, 1830–1865," American Art Journal 10(1): 72–89.

- Mott, Frank Luther. 1930. A History of American Magazines, Volume 1 (1741–1850). Harvard University Press/ Belknap. ISBN 0-674-39550-6.

- Spivey, Herman Everette (1936). The Knickerbocker Magazine, 1833–1865: A Study of its History, Contents, and Significance (PhD thesis). University of North Carolina.

References

- Callow, James T. Kindred Spirits: Knickerbocker Writers and American Artists, 1807–1855. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1967: 104.

- Callow 1967, p. 102.

- Nash, Roderick F (2001). Wilderness and the American Mind (4th ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 97–99.

- Pattee, Fred Lewis (1966). The First Century of Literature: 1770–1870. New York: Cooper Square Publishers. p. 493.

- Barnes, Homer (1930). Charles Fenno Hoffman. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 44.

- Miller, Perry. The Raven and the Whale: The War of Words and Wits in the Era of Poe and Melville. New York: Harvest Book, 1956: 11–12.

- Miller 1956, p. 12.

- Miller 1956, p. 13.

- Jones, Brian Jay (2008). Washington Irving: An American Original. New York: Arcade. p. 333. ISBN 978-1-55970-836-4.

- Nelson, Randy F. The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981: 30. ISBN 0-86576-008-X

- "Morris Phillips" (obituary), Daily Standard Union (Brooklyn), August 31, 1904, p. 4, col. 5 of 7

- Riis, Jacob A. (2009). How the other half lives: studies among the tenements of New York. Lawrence, Kansas: Digireads.com Pub. ISBN 978-1-4209-2503-6.

- Jones, Brian Jay (2007). Washington Irving: an American original (1 ed.). New York: Arcade. ISBN 978-1-55970-836-4.

- Wolfert's Roost and Miscellanies by Washington Irving. Boston: MobileReference.com. 2008. ISBN 978-1-60501-996-3.

- Knickerbocker, Howard. "Knickerbocker History (Some Thoughts On The Origins Of The Name)". Knickerbocker Genealogy. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- The Knickerbocker, Volume 2 Volumes 349–360 of American periodical series, 1800–1850. New York, New York: Peabody, 1833. 1833. ASIN B002YD7K36. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- The Knickerbocker, or The New York Monthly. March 1847: 283.

- Pemberton, S. George (2010). "History of Ichnology: Early Ichnology Poems and Their Poets". Ichnos. 17 (4): 264–270. doi:10.1080/10420940.2010.535450.

- Bender, Thomas (1987). "New York Intellect: A History of Intellectual Life in New York City, 1750 to the Beginnings of Our Own Time". New York: Alfred A. Knopf: 141. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Cited in Kaufman, Eric (1998). "Naturalizing the Nation: The Rise of Naturalistic Nationalism in the United States and Canada". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 40 (4): 672. JSTOR 179306. - Jacobs, Wilbur R. (1992). "Francis Parkman: Naturalist-Environmental Savant". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (3): 341–356. doi:10.2307/3640591. JSTOR 3640591.

- Curti, Merle (1953). "Human Nature in American Thought". Political Science Quarterly. 68 (3): 354–375. doi:10.2307/2145605. JSTOR 2145605.

- "James Russell Lowell". Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Bertonneau, Thomas F. "James Russell Lowell". Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Hoffman, Charles Fenno (1844). The Knickerbocker: Or, New-York Monthly Magazine. 23. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Madden, J. "The Origin of the Name "Moby Dick"". Retrieved 27 November 2012.

External links

- The Knickerbocker at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- The Knickerbacker v. 1 at Google Book Search

- The Knickerbocker v. 2 at Google Book Search

- The Knickerbocker at Ron Unz's site

- The Knickerbocker at the HathiTrust