The Gentlewoman

The Gentlewoman was a weekly illustrated paper for women founded in 1890 and published in London.

For its first thirty-six years its full title was The Gentlewoman: An Illustrated Weekly Journal for Gentlewomen.[1] In 1926 it was briefly renamed Gentlewoman and Modern Life, and ceased publication later the same year, to be merged with Eve: The Lady's Pictorial.

History

Publishing its first issue on 12 July 1890,[1] The Gentlewoman soon established a reputation for good writing. On 15 December 1891 The Times reported that its Christmas number had

...stories, all illustrated in colours, by Mr Farjeon, Mr Grant Allen, Mr Doyle, Lord Brabourne, Miss Florence Warden, Mrs Campbell Praed, Mr Henry Herman, and Mr A. J. Pask, and the beginning of a novel, produced under exceptional conditions, "The Fate of Fenella".[2]

This unusual "consecutive novel", in which each chapter was written by a different author, was serialized between December 1891 and April 1892.[3][4] The Gentlewoman's editor, Joseph Snell Wood, devised the idea and arranged for male and female writers to alternate in developing the narrative. Those he secured for the project included Bram Stoker, Frances Eleanor Trollope, Florence Marryat, Mrs Hungerford, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Mrs Edward Kennard. Stoker's chapter, called "Lord Castleton Explains", appeared in January 1892.[5] The Times commented at the outset that "The result of so peculiar an experiment will be awaited with some curiosity."[2] The complete work was published as a three volume novel by Hutchinson of London in May 1892,[3] and a review of it noted the absence of a controlling mind.[4]

In 1892 The Gentlewoman employed E. W. Hornung, later famous as the creator of A. J. Raffles, as an assistant editor.[6]

In 1893 the paper launched a campaign against "tight-lacing", the fad for ever-smaller waists created by very tight corsets, which it described as "this modern madness" and "this pernicious habit".[7]

In 1894 the editor, J. S. Wood, founded the Society of Women Journalists.[8] In May of the same year, the paper published The Gentlewoman Handbook of Education: What a Parent Should Know, by "Dominie".[9]

In 1895 Margaret Wolfe Hungerford's novel A Point of Conscience first appeared as a serial in The Gentlewoman.[10] In November of that year, Mary Anne Keeley addressed a ninetieth birthday message to her fellow-actresses by way of a letter to The Gentlewoman which was reported in The Times.[11]

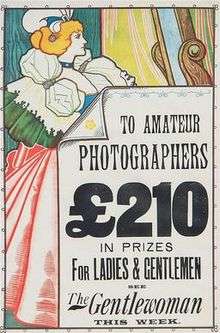

In 1896 J. S. Wood and A. J. Warden were reported to be the proprietors of The Gentlewoman,[12] and in 1898 preference shares in the paper were listed on the London Stock Exchange.[13] Also in 1898, the Grafton Galleries hosted an exhibition of the winning images from the paper's photographic competition, open to amateur photographers only. The Gentlewoman had offered two hundred guineas in prizes, and the judges were H. P. Robinson, Viscount Maitland, and the Rev. F. C. Lambert.[14]

In July 1897 Arthur Mulliner took two of the paper's women journalists from Northampton to London in a Daimler, and they asked why he called the car "she". When he replied that it was because "it took a man to manage her", they proved him wrong by both taking a turn at the wheel. They later reported the journey to have been like "tobogganing or riding on a switchback railway".[15]

The Gentlewoman celebrated the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria with The Gentlewoman's Record of the Glorious Reign of Victoria the Good, by the paper's editor, J. S. Wood.[16] The next year, 1898, the London periodical Truth reported that

"The Gentlewoman has gained for itself a reputation and position of stability which is without parallel in the history of any similar Journal, having regard to the number of years it has been established. Its high tone and artistic and literary excellence have made it a popular weekly newspaper."[17]

In 1900 the paper published the first instalment of Marie Bashkirtseff's journals and letters to Guy de Maupassant,[18] and Lord Alfred Douglas's friend T. W. H. Crosland was a regular contributor.[19]

In 1902 the popular novelist Marie Corelli wrote to the editor of The Gentlewoman to complain that her name had been left out of a list of the guests in the Royal Enclosure at the Braemar Highland Gathering, and she suspected that this had been done intentionally. Wood replied from his office in the Strand that her name had indeed been left out intentionally, because of her own stated contempt for the press and for the snobbery of those wishing to appear in the "news puffs" of society events. Both letters were published in full in the next issue of the paper.[20]

In 1906 the composer Marian Arkwright received a prize from The Gentlewoman for her orchestral work called The Winds of the World.[21]

In June 1918, it was through The Gentlewoman that Princess Mary announced she was to train as a nurse at the Great Ormond Street Hospital.[22]

In 1919 the paper gave its name to "The Gentlewoman Tournament", the first Girls Amateur Championship, which was won by Audrey Croft.[23] In 1925 it was organized from the offices of the paper, then based at 69–77 Long Acre, London WC2.[24]

At the beginning of 1926 the publication was renamed Gentlewoman and Modern Life, but only seven months later it was merged with a women's magazine called Eve: The Lady's Pictorial and ceased publication. The last issue was dated 7 August 1926.[25][26] In April 1927 The Gentlewoman Illustrated Limited went into voluntary liquidation and was wound up.[27]

Notes

- Nos. 1 to 1,853 dated between 12 July 1890 and 2 January 1926; see Victorian Illustrated Newspapers and Journals: Select list at bl.uk, web site of the British Library, accessed 21 February 2014

- 'Christmas Numbers' in The Times, issue 33508 dated 15 December 1891, p. 6

- The Fate of Fenella at bramstoker.org, accessed 21 February 2012

- The Fate of Fenella from The Spectator dated May 1892, at spectator.co.uk, accessed 21 February 2014

- "Lord Castleton Explains", Chapter 10 of The Fate of Fenella, in The Gentlewoman dated 30 January 1892

- Gyles Brandreth, Oscar Wilde and a Game Called Murder: A Mystery (2008), p. 317

- 'The sin and scandal of tight-lacing' in The West Australian dated Tuesday 17 January 1893

- Peter Gordon, David Doughan, Dictionary of British Women's Organisations: 1825–1960 (Routledge, 2001, ISBN 978-0-7130-4045-6), p. 135

- 'Publications To-Day' in The Times, issue 34267 dated 18 May 1894, p. 6

- British Books, vol. 10 (1895), p. 102: "The Gentlewoman contains the first chapters of a new story by Mrs Hungerford, entitled 'A Point of Conscience'."

- 'Court Circular' in The Times, issue 34740 dated 21 November 1895, p. 5

- 'The Sala Memorial Fund' in The Times, issue 34990 dated 8 September 1896, p. 6

- 'Stocks and Shares' in The Times, issue 35680 dated 22 November 1898, p. 11

- Henry Snowden Ward, Process: The Photomechanics of Printed Illustration (1898), p. 266

- Lord Montagu, David Burgess-Wise, Daimler Century (Stephens, 1995, ISBN 1-85260-494-8), p. 47

- The National Union Catalog, vol. 672 (Mansell, 1980), p. 269

- Truth, vol. 44 (1898), p. 261

- The Academy, vol. 59 (1900), p. 572

- Henry Robert Addison et al., eds., 'Crosland, Thomas William Hodgson' in Who's Who, vol. 59 (1907), p. 418

- Teresa Ransom, The Mysterious Miss Marie Corelli: Queen of Victorian Bestsellers (2013), p. 100

- The Monthly Musical Record, vol. 36 (1906), p. 89

- 'Court Circular' in The Times, issue 41826 dated 26 June 1918, p. 9

- 'The Girls' Championship: A Great Match' (from a Special Correspondent) in The Times, issue 42209 dated 19 September 1919, p. 5

- 'Golf' (by our Golf correspondent) in The Times, issue 44040 dated 14 August 1925, p. 5

- "Britannia and Eve". British Newspaper Archive. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Nos. 1,854 to 1,883, 9 January to 7 August 1926

- The London Gazette dated 15 April 1927, p. 2,504