The Fox Hunt (painting)

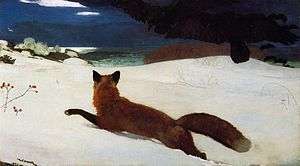

The Fox Hunt is an 1893 oil on canvas painting by Winslow Homer. It depicts a fox running in deep snow, menaced by hungry crows. His largest single work, it has been described as "Homer's greatest Darwinian painting, arguably his greatest painting of any kind."[1]

The Fox Hunt was painted in Homer's studio at Prouts Neck, Maine during the winter of 1893. The painting depicts a fox foraging for food, who is in turn being hunted by crows driven to predation by hunger.[2][3] At left several sprigs of red berries breach the snow, and in the distance may be seen the coastline and ocean beneath a deep blue sky.

Painting

According to Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., the artist used a fox's pelt draped over a barrel in the snow to accurately record color harmonies.[2] Homer's biographer Philip C. Beam wrote that prior to the painting Homer was supplied a dead fox by one hunter, and several crows by another named Roswell Googins.[4] Homer placed the crows in the snow outside his studio, and with the aid of string and sticks posed the fox in a running position. Homer experienced some difficulty, as the painting was begun late in winter, and warming temperatures caused the stiffened crows to thaw and grow limp.[4] Homer asked Elbridge Oliver, the Scarborough, Maine stationmaster for his opinion of the painting, and he responded "Hell, Win, them ain't crows".[4] After painting the birds out, Homer joined Oliver at the station, where they spent three days scattering corn on the ground to attract crows, Homer sketching the birds on telegraph blanks.[4] Using the sketches as reference he repainted the crows, then summoned Oliver for his opinion and approval.[4]

Interpretation

When exhibited in 1893, the Darwinian aspect of the painting was immediately recognized by critics: "A fox makes his way through the snow, looking sharply at his enemies— two huge crows which are swooping down to devour him, in which their hunger, made savage by the snowstorm which has covered their usual hunting-ground. Other crows hover restlessly in the distance. A twig or two of last summer's wild-rose bush is the grace note of the picture, redeeming sufficiently the sombre character of the scene".[5]

Several writers on Homer's work have seen evidence of the artist's self-disclosure in The Fox Hunt. Seeing the picture in Freudian terms, Thomas B. Hess believed the fox, "dapper, small, inquisitive, shrewd", was a self-portrait.[6][7] Cikovsky noted that the artist's signature is "sinking like the fox into the deep snow and exactly mimicking its form and action", and adds that the fox's tail, repeated by the 'R' in the signature, is called a brush.[6] It is possible that Homer identified with slyness and social aloofness, qualities attributed to the fox.[6] As well, the crows have been seen as omens of death,[6] and for Hess, basing his interpretation on Freud's study of Leonardo da Vinci's work, they represent "the nightmare of the flying 'penis'".[7]

The influence of Japanese design on Homer's work has been noted generally, and particularly in The Fox Hunt, with the observation that the painting can be divided into three vertical panels, thereby creating "a perfect Japanese screen".[8] The Fox Hunt was purchased from the artist in 1894 by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, after it was exhibited in the academy's annual show.[9]

Notes

- Cikovsky, 253

- Cikovsky, 236

- William Howe Downes (1911). The life and works of Winslow Homer. Houghton Mifflin company. p. 168.

- Little, 46

- Cikovsky, 381

- Cikovsky, 254

- Cikovsky, 379

- Gardner, 112, 206

- Gardner, 202

References

- Beam, Philip. Winslow Homer at Prout's Neck. 1966

- Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr; Franklin Kelly; Winslow Homer (1995). Winslow Homer. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-217-9.

- Gardner, Albert Ten Eyck. Winslow Homer, American Artist: his World and his Work. Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., New York: 1961

- Little, Carl. Winslow Homer and The Sea. Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995.

Further reading

- William Howe Downes (1911). The life and works of Winslow Homer. Houghton Mifflin company. p. 168.

External links

- The Fox Hunt's entry at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts