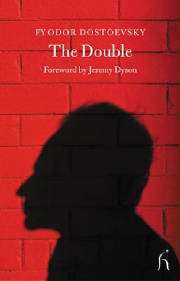

The Double (Dostoevsky novel)

The Double (Russian: Двойник, Dvoynik) is a novella written by Fyodor Dostoevsky. It was first published on January 30, 1846 in the Fatherland Notes.[1] It was subsequently revised and republished by Dostoevsky in 1866.[2]

Plot summary

In Saint Petersburg, Yakov Petrovich Golyadkin works as a titular councillor (rank 9 in the Table of Ranks established by Peter the Great.[3]), a low-level bureaucrat struggling to succeed.

Golyadkin has a formative discussion with his Doctor Rutenspitz, who fears for his sanity and tells him that his behaviour is dangerously antisocial. He prescribes "cheerful company" as the remedy. Golyadkin resolves to try this, and leaves the office. He proceeds to a birthday party for Klara Olsufyevna, the daughter of his office manager. He was uninvited, and a series of faux pas lead to his expulsion from the party. On his way home through a snowstorm, he encounters a man who looks exactly like him, his double. The following two thirds of the novel then deals with their evolving relationship.

At first, Golyadkin and his double are friends, but Golyadkin Jr. proceeds to attempt to take over Sr.'s life, and they become bitter enemies. Because Golyadkin Jr. has all the charm, unctuousness and social skills that Golyadkin Sr. lacks, he is very well-liked among the office colleagues. At the story's conclusion, Golyadkin Sr. begins to see many replicas of himself, has a psychotic break, and is dragged off to an asylum by Doctor Rutenspitz.

Influences

The Double is the most Gogolesque of Dostoevsky's works; its subtitle "A Petersburg Poem" echoes that of Gogol's Dead Souls. Vladimir Nabokov called it a parody of "The Overcoat". Many others have emphasised the relationship between The Double and other of Gogol's Petersburg Tales. One contemporary critic, Konstantin Aksakov, remarked that "Dostoevsky alters and wholly repeats Gogol’s phrases."[4] Most scholars, however, recognise The Double as Dostoevsky’s response to or innovation on Gogol’s work. For example, A.L. Bem called The Double "a unique literary rebuttal" to Gogol's story "The Nose".[5]

This immediate relationship is the obvious manifestation of Dostoevsky's entry into the deeper tradition of German Romanticism, particularly the writings of E. T. A. Hoffmann.

Critical reception

The Double has been interpreted in a number of ways. Looking backwards, it is viewed as Dostoevsky's innovation on Gogol. Looking forwards, it is often read as a psychosocial version of his later ethical-psychological works.[6] These two readings, together, position The Double at a critical juncture in Dostoevsky's writing at which he was still synthesizing what preceded him but also adding in elements of his own. One such element was that Dostoevsky switched the focus from Gogol's social perspective in which the main characters are viewed and interpreted socially to a psychological context that gives the characters more emotional depth and internal motivation.[7]

As to the interpretation of the work itself, there are three major trends in scholarship. First, many have said that Golyadkin simply goes insane, probably with schizophrenia.[8] This view is supported by much of the text, particularly Golyadkin's innumerable hallucinations.

Second, many have focused on Golyadkin's search for identity. One critic wrote that The Double's main idea is that "'the human will in its search for total freedom of expression becomes a self-destructive impulse.’"[9]

This individualistic focus is often contextualized by scholars, such as Joseph Frank, who emphasize that Golyadkin's identity is crushed by the bureaucracy and stifling society he lives in.[10]

The final context of understanding for The Double that transcends all three categories is the ongoing debate about its literary quality. While the majority of scholars have regarded it as somewhere from "too fragile to bear its significance"[11] to utterly unreadable, there have been two notable exceptions. Dostoevsky wrote in A Writer's Diary that "Most decidedly, I did not succeed with that novel; however, its idea was rather lucid, and I have never expressed in my writings anything more serious. Still, as far as form was concerned, I failed utterly."[12] Vladimir Nabokov, who generally regarded Dostoevsky as a "rather mediocre" writer called The Double "the best thing he ever wrote," saying that it is "a perfect work of art."[13]

Adaptations

The story was adapted into a British movie (The Double (2013 film), starring Jesse Eisenberg.[14]

A one-hour radio adaptation by Jonathan Holloway and directed by Gemma Jenkins, changing the time period from Tsarist Russia to "a steampunk version of 19th Century St Petersburg",[15] was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 as part of their Dangerous Visions series on 10 June 2018. The cast included Joseph Millson as Golyadkin/The Double and Elizabeth Counsell as Dr. Rutenspitz.

The 2004 psychological thriller film The Machinist was heavily influenced by Dostoevsky's story.

References

![]()

- Mochulsky, Konstantin (1973) [First published 1967]. Dostoevsky: His Life and Work. Trans. Minihan, Michael A. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-691-01299-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor (1984). "Translator's Introduction". The double : two versions. Translated by Harden, Evelyn J. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis. pp. ix–xxxvi. ISBN 0882337572.

- Gogol, Nikolaĭ Vasilʹevich (1998). "Introduction". Plays and Petersburg tales : Petersburg tales, marriage, the government inspector. Translated by English, Christopher. Introduction by Richard Peace. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks. pp. vii–xxx. ISBN 9780199555062.

- Konstantin Aksakov, qtd. in Mochulsky, Dostoevsky: zhizn I tvorchestvo (Paris, 1947): 59, qtd in. Fanger, Donald. Dostoevsky and Romantic Realism: A Study of Dostoevsky in Relation to Balzac, Dickens, and Gogol. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965, 159.

- Bem, A. L. (1979). "The Double and The Nose". In Meyer, Priscilla; Rudy, Stephen (eds.). Dostoevsky & Gogol : texts and criticism. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis. p. 248. ISBN 0882333151.

- Chizhevsky, Dmitri (1965). "The theme of the dougle in Dostoevsky". In Wellek, René (ed.). Dostoevsky : a collection of critical essays. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. pp. 112–29.

- Valerian Maykov in Terras, Victor. "The Young Dostoevsky: An Assessment in the Light of Recent Scholarship." In New Essays on Dostoevsky, edited by Malcolm V. Jones and Garth M. Terry, 21-40. Bristol, Great Britain: Cambridge University Press, 1983, 36.

- Rosenthal, Richard J. "Dostoevsky's Experiment with Projective Mechanisms and the Theft of Identity in The Double." In Russian Literature and Psychoanalysis, 59-88. Vol. 31. Linguistic & Literary Studies in Eastern Europe. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1989, 87.

- W. J. Leatherbarrow "The Rag with Ambition: The Problem of Self-Will in Dostoevsky's "Bednyye Lyudi" and "Dvoynik""

- Frank, Joseph. "The Double." In The Seeds of Revolt: 1821-1849., 295-312. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979, 300.

- Frank, The Seeds of Revolt, 295.

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. "The History of the Verb "Stushevatsia"" In Diary of a Writer, translated by Boris Brasol, 882-85. Vol. II. New York, N.Y.: Octagon Books, 1973, 883.

- Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich. "Fyodor Dostoevski." In Lectures on Russian Literature, compiled by Fredson Bowers, 97-136. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich/Bruccoli Clark, 1981, 68.

- "Jesse Eisenberg, Mia Wasikowska Join 'The Double' Cast". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0b5s5t6

External links

- Full text of The Double in the original Russian