The Blood of Others

The Blood of Others (French: Le Sang des autres) is a novel by the French existentialist Simone de Beauvoir first published in 1945 and depicting the lives of several characters in Paris leading up to and during the Second World War. The novel explores themes of freedom and responsibility.

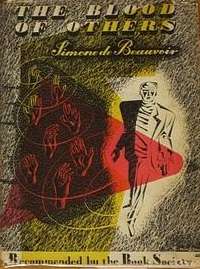

First UK edition | |

| Author | Simone de Beauvoir |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le Sang des autres |

| Cover artist | Victor Reinganum |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Philosophical novels |

| Publisher | Gallimard |

Publication date | 1945 (1st edition) |

Published in English | 1948 Knopf (US) Secker & Warburg (UK) |

Plot summary

In German-occupied France, Jean Blomart sits by a bed in which his lover Hélène lies dying. Through a series of flashbacks, we learn about both characters and their relationship to each other. As a young man filled with guilt about his privileged middle-class life, Jean joins the Communist Party and breaks from his family, determined to make his own way in life. After the death of a friend in a political protest, for which he feels guilty, Jean leaves the Party and concentrates on trade union activities. Hélène is a young designer who works in her family's confectionery shop and is dissatisfied with her conventional romance with her fiancé Paul. She contrives to meet Jean and, though he initially rejects her, they form a relationship after she has had an abortion following a reckless liaison with another man. Caring for her happiness, Jean tells Hélène he loves her even though he believes that he does not. He proposes and she accepts.

When France enter the Second World War, Jean, conceding the need for violent conflict to effect change, becomes a soldier. Hélène intervenes against his will to arrange a safe posting for him. Angry with her, Jean breaks their relationship. As the German forces advance towards Paris, Hélène flees and witnesses the suffering of other refugees. Returning to Paris, she briefly takes up with a German who could advance her career, but soon sees what her countrymen are suffering. She also witnesses the roundup of Jews. Securing the safety of her Jewish friend Yvonne leads Hélène back to Jean who has become a leader in a Résistance group. She is moved to join the group. Jean has reconnected with his father with the common goal to liberate France from Germany. His mother however is less impressed by the lives lost to the Resistance. Hélène is shot in a resistance activity and during Jean's night vigil at her side, he examines his love for Hélène and the wider consequences of his actions. As morning dawns, Hélène dies and Jean decides to continue with acts of resistance.

Major themes

The major theme of The Blood of Others is the relation between the free individual and 'the historically unfolding world of brute facts and other men and women.'[1] Or as one of Beauvoir's biographers puts it, her 'intention was to express the paradox of freedom experienced by an individual and the ways in which others, perceived by the individual as objects, were affected by his actions and decisions.' [2]

Another theme of the novel, though not unrelated to the first, is 'the issue of resistance versus collaboration'. Beauvoir seems to be saying that to not actively resist the German occupation is in effect to accept it. This, argues David E. Cooper, is an illustration of an existentialist view of the nature of freedom, according to which an individual is just as responsible for not refusing something as for choosing it. Any distinction between choosing and not refusing is elided.[3]

Creative process

Beauvoir began writing The Blood of Others in 1941,[4] and it was 'essentially finished' by May 1943.[5] Beauvoir wrote it in the Café de Flore in Paris, arriving at 8am each morning, because the café was heated while the hotel in which she lived was not.[6] Beauvoir used some of her own experiences for the novel.:[7] Hélène's fleeing from Paris as the Germans advanced is based on Beauvoir's own actions - in June 1940 she travelled with friends by car to Laval and then by coach to Angers. Blomart's reaction to the death of the baby son of his family's maid (chapter 1) is based on Beauvoir's own experience of the same as a young woman. The story of Madeleine volunteering to help in the Spanish civil War and injuring her foot by spilling hot water over it is based on a similar event that occurred to writer Simone Weil. According to another source, much of Hélène's behaviour is based on that of Nathalie Sorokine, a pupil and friend of Beauvoir's and to whom The Blood of Others is dedicated.[8]

Critical reception

According to biographer Deirdre Bair, the novel received a 'barrage of praise that was showered upon it.' [2] One reviewer wrote that Beauvoir had written 'in an economical, sometimes flat style which conceals a remarkably sustained note of suspense and mounting excitement due to the sheer vitality and force of her ideas. This is perhaps the way a novel of ideas should be presented.' [9] Fifteen years later in 1960, Beauvoir herself was critical of the book, saying that the characters were too thin and the novel too didactic.[10]

Publication history

Le Sang des Autres (the novel's title in French) was first published in 1945 by Gallimard. The English translation by Yvonne Moyse and Roger Senhouse was first published by Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd and Lindsay Drummond in 1948. The same translation was published by Penguin Books in 1964, has been republished in paperback several times and is probably the most widely available edition of the novel in English. ISBN 0-14-018333-7 [11]

Film

- The Blood of Others (1984) directed by Claude Chabrol, starring Jodie Foster.

References

- Stella Sanford, How to Read Beauvoir (Granta Books, London, 2006) p. 11.

- Deirdre Bair, Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography (Jonathan Cape, London, 1990) p. 305.

- David E. Cooper, Existentialism (Second edition, Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA, 1990) p. 161-162.

- Margaret Crosland, Simone de Beauvoir: The Woman and Her Work (Heinemann, London, 1992) p. 327.

- Deirdre Bair, Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography (Jonathan Cape, London, 1990) p. 277.

- Deirdre Bair, Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography (Jonathan Cape, London, 1990) p. 273.

- The following information is from Margaret Crosland, Simone de Beauvoir: The Woman and Her Work (Heinemann, London, 1992) p. 267, 328.

- Deirdre Bair, Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography (Jonathan Cape, London, 1990) p. 237.

- Richard McLaughlin, 'Mouthing Basic Existentialism,' Saturday Review of Literature, July 17, 1948, p. 13, quoted in Deirdre Bair, Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography (Jonathan Cape, London, 1990) p. 306-307.

- Margaret Crosland, Simone de Beauvoir: The Woman and Her Work (Heinemann, London, 1992) p. 328.

- All information in this section is from the publication details in the Penguin paperback edition of The Blood of Others.