The Bell Jar

The Bell Jar is the only novel written by the American writer and poet Sylvia Plath. Originally published under the pseudonym "Victoria Lucas" in 1963, the novel is semi-autobiographical, with the names of places and people changed. The book is often regarded as a roman à clef because the protagonist's descent into mental illness parallels Plath's own experiences with what may have been clinical depression or bipolar II disorder. Plath died by suicide a month after its first UK publication. The novel was published under Plath's name for the first time in 1967 and was not published in the United States until 1971, in accordance with the wishes of both Plath's husband, Ted Hughes, and her mother.[2] The novel has been translated into nearly a dozen languages.[3]

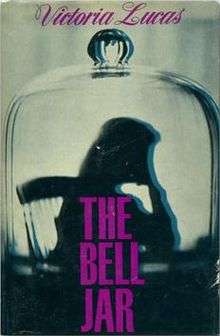

First edition cover, published under Sylvia Plath's pseudonym, "Victoria Lucas." | |

| Author | Sylvia Plath |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Roman à clef |

| Publisher | Heinemann |

Publication date | January 14, 1963[1] |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 244 |

Plot summary

In 1953, Esther Greenwood, a young woman from the suburbs of Boston, gains a summer internship at a prominent magazine in New York City, under editor Jay Cee; however, Esther is neither stimulated nor excited by the big city, nor by the glamorous culture and lifestyle that girls her age are expected to idolize and emulate. She instead finds her experience to be frightening and disorienting; appreciating the witty sarcasm and adventurousness of her friend Doreen, but also identifying with the piety of Betsy (dubbed "Pollyanna Cowgirl"), a "goody-goody" sorority girl who always does the right thing. She has a benefactress in Philomena Guinea, a formerly successful fiction writer (based on Olive Higgins Prouty).

Esther describes in detail several seriocomic incidents that occur during her internship, kicked off by an unfortunate but amusing experience at a banquet for the girls held by the staff of Ladies' Day magazine. She reminisces about her friend Buddy, whom she has dated more or less seriously, and who considers himself her de facto fiancé. She also muses about Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who are scheduled for execution. Soon before the internship ends, she attends a country club party with Doreen and is set up with a man who treats her roughly and nearly rapes her, before she breaks his nose and leaves. That night, after returning to the hotel, she throws all of her clothes off the roof.

The day after, she returns to her Massachusetts home in borrowed clothes from Betsy and still bloodied from the night before. She has been hoping for another scholarly opportunity once she is back in Massachusetts, a writing course taught by a world-famous author, but on her return she is immediately told by her mother that she was not accepted for the course and finds her plans derailed. She decides to spend the summer potentially writing a novel, although she feels she lacks enough life experience to write convincingly. All of her identity has been centered upon doing well academically; she is unsure of what to make of her life once she leaves school, and none of the choices presented to her (motherhood, as exemplified by the prolific child-bearer Dodo Conway, or stereotypical female careers such as stenography) appeal to her. Esther becomes increasingly depressed, and finds herself unable to sleep. Her mother encourages, or perhaps forces, her to see a psychiatrist, Dr. Gordon, whom Esther mistrusts because he is attractive and seems to be showing off a picture of his charming family rather than listening to her. He prescribes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); and afterward, she tells her mother that she will not go back.

Esther's mental state worsens. She makes several half-hearted attempts at suicide, including swimming far out to sea, before making a serious attempt. She leaves a note saying she is taking a long walk, then crawls into a hole in the cellar and swallows about 50 sleeping pills that had been prescribed for her insomnia. In a very dramatic episode, the newspapers presume her kidnapping and death, but she is discovered under her house after an indeterminate amount of time. She survives and is sent to several different mental hospitals until her college benefactress, Philomena Guinea, supports her stay at an elite treatment center where she meets Dr. Nolan, a female therapist. Along with regular psychotherapy sessions, Esther is given huge amounts of insulin to produce a "reaction," and again receives shock treatments, with Dr. Nolan ensuring that they are properly administered. While there, she describes her depression as a feeling of being trapped under a bell jar, struggling for breath. Eventually, Esther describes the ECT as beneficial in that it has a sort of antidepressant effect; it lifts the metaphorical bell jar in which she has felt trapped and stifled. While there, she also becomes reacquainted with Joan Gilling, who also used to date Buddy.

Esther tells Dr. Nolan how she envies the freedom that men have and how she, as a woman, worries about getting pregnant. Dr. Nolan refers her to a doctor who fits her for a diaphragm. Esther now feels free from her fears about the consequences of sex; free from previous pressures to get married, potentially to the wrong man. Under Dr. Nolan, Esther improves and various life-changing events, such as losing her virginity and Joan's suicide, help her to regain her sanity. The novel ends with her entering the room for an interview, which will decide whether she can leave the hospital and return to school.

It is suggested near the beginning of the novel that, in later years, Esther goes on to have a baby.

Characters

- Esther Greenwood is the protagonist of the story, who becomes mentally unstable during a summer spent interning at a magazine in New York City. Tormented by both the death of her father and the feeling that she simply does not fit into the culturally acceptable role of womanhood, she attempts suicide in the hopes of escape.

- Doreen is a rebel-of-the-times young woman and another intern at Ladies' Day, the magazine for which Esther won an internship for the summer, and Esther's best friend at the hotel in New York where all the interns stay. Esther finds Doreen's confident persona enticing but also troublesome, as she longs for the same level of freedom but knows such behavior is frowned upon.

- Joan is an old acquaintance of Esther, who joins her at the asylum and eventually dies by suicide.

- Doctor Nolan is Esther's doctor at the asylum. A beautiful and caring woman, her combination of societally praised femininity and professional ability allows her to be the first woman in Esther's life she feels she can fully connect with. Nolan administers shock therapy to Esther and does it correctly, which leads to positive results.

- Doctor Gordon is the first doctor Esther encounters. Self-obsessed and patronizing, he subjects her to traumatic shock treatments that haunt her for the rest of her time in medical care.

- Mrs. Greenwood, Esther's mother, loves her daughter but is constantly urging Esther to mold to society's ideal of white, middle-class womanhood, from which Esther feels a complete disconnection.

- Buddy Willard is Esther's former boyfriend from her hometown. Studying to become a doctor, Buddy wants a wife who mirrors his mother, and hopes Esther will be that for him. Esther adores him throughout high school, but upon learning he is not a virgin loses respect for him and names him a hypocrite. She struggles with ending the relationship after Buddy is diagnosed with tuberculosis. He eventually proposes to her, but Esther refuses due to the decision that she will never marry, to which Buddy responds that she is crazy.

- Mrs. Willard, Buddy Willard's mother, is a dedicated homemaker who is determined to have Buddy and Esther marry.

- Mr. Willard, Buddy Willard's father and Mrs. Willard's husband, is a good family friend.

- Constantin, a simultaneous interpreter with a foreign accent, takes Esther on a date while they are both in New York. They return to his apartment and Esther contemplates giving her virginity to him, but he is not attracted to her.

- Irwin is a tall but rather ugly young man, who gives Esther her first sexual experience, causing her to hemorrhage. He is a "very well-paid professor of mathematics" and invites Esther to have coffee, which leads to her having sex with him, and as a result, leads to Esther having to go to the hospital to get help to stop the bleeding.

- Jay Cee is Esther's strict boss, who is very intelligent, so "her plug-ugly looks didn't seem to matter".[4] She is responsible for editing Esther's work.

- Lenny Shepherd, a wealthy young man living in New York, invites Doreen and Esther for drinks while they are on their way to a party. Doreen and Lenny start dating, taking Doreen away from Esther more often.

- Philomena Guinea, a wealthy, elderly lady, was the person who donated the money for Esther's college scholarship. Esther's college requires each girl who is on scholarship to write a letter to her benefactor, thanking him or her. Philomena invites Esther to have a meal with her. At one point, she was also in an asylum herself, and pays for the "upscale" asylum that Esther stays in.

- Marco, a Peruvian man and friend of Lenny Shepherd, is set up to take Esther to a party and ends up attempting to rape her.

- Betsy, a wealthier girl from the magazine, is a "good" girl from Kansas whom Esther strives to be more like. She serves as the opposite to Doreen, and Esther finds herself torn between the two behavioral and personality extremes.

- Hilda is another girl from the magazine, who is generally disliked by Esther after making negative comments about the Rosenbergs.

Publication history

According to her husband, Plath began writing the novel in 1961, after publishing The Colossus, her first collection of poetry. Plath finished writing the novel in August 1961.[5] After she separated from Hughes, Plath moved to a smaller flat in London, "giving her time and place to work uninterruptedly. Then at top speed and with very little revision from start to finish she wrote The Bell Jar,"[3] he explained.

Plath was writing the novel under the sponsorship of the Eugene F. Saxton Fellowship, affiliated with publisher Harper & Row, but it was disappointed by the manuscript and withdrew, calling it "disappointing, juvenile and overwrought."[3] Early working titles of the novel included Diary of a Suicide and The Girl in the Mirror.[6]

Style and major themes

The novel is written using a series of flashbacks that show up parts of Esther's past. The flashbacks primarily deal with Esther's relationship with Buddy Willard. The reader also learns more about her early college years.

The Bell Jar addresses the question of socially acceptable identity. It examines Esther's "quest to forge her own identity, to be herself rather than what others expect her to be."[7] Esther is expected to become a housewife, and a self-sufficient woman, without the options to achieve independence.[6] Esther feels she is a prisoner to domestic duties and she fears the loss of her inner self. The Bell Jar sets out to highlight the problems with oppressive patriarchal society in mid-20th-century America.[8]

Mental health

Esther Greenwood, the main character in The Bell Jar, describes her life as being suffocated by a bell jar. Analysis of the phrase "bell jar" shows it represents "Esther's mental suffocation by the unavoidable settling of depression upon her psyche".[9] Throughout the novel, Esther talks of this bell jar suffocating her and recognizes moments of clarity when the bell jar is lifted. These moments correlate to her mental state and the effect of her depression. Scholars argue about the nature of Esther's "bell jar" and what it can stand for.[9] Some say it is a retaliation against suburban lifestyle,[10] others believe it represents the standards set for a woman's life.[8] However, when considering the nature of Sylvia Plath's own life and death and the parallels between The Bell Jar and her life, it is hard to ignore the theme of mental illness.[11]

Psychiatrist Aaron Beck studied Esther's mental illness and notes two causes of depression evident in her life.[12] The first is formed from early traumatic experiences, her father's death when she was 9 years old. It is evident how affected she is by this loss when she wonders, "I thought how strange it had never occurred to me before that I was only purely happy until I was nine years old."[13] The second cause of her depression is from her perfectionist ideologies. Esther is a woman of many achievements – college, internships and perfect grades. It is this success that puts the unattainable goals into her head, and when she doesn't achieve them, her mental health suffers. Esther laments, "The trouble was, I had been inadequate all along, I simply hadn't thought about it."[13]

Esther Greenwood has an obvious mental break – that being her suicide attempt which dictates the latter half of the novel.[13] However, Esther's entire life shows warning signs that cause this depressive downfall. The novel begins with her negative thoughts surrounding all her past and current life decisions. It is this mindset mixed with the childhood trauma and perfectionist attitude that causes her descent that leads her to attempt suicide.[14]

This novel gives an account of the treatment of mental health in the 1950s.[15] Plath speaks through Esther's narrative to describe her experience of her mental health treatment. Just as this novel gives way to feminist discourse and challenges the way of life for women in the 1950s, it also gives a case study of a woman struggling with mental health.[16]

Parallels between Plath's life and the novel

The book contains many references to real people and events in Plath's life. Plath's magazine scholarship was at Mademoiselle magazine beginning in 1953.[17] Philomena Guinea is based on author Olive Higgins Prouty, Plath's own patron, who funded Plath's scholarship to study at Smith College. Plath was rejected from a Harvard course taught by Frank O'Connor.[18] Dr. Nolan is thought to be based on Ruth Beuscher, Plath's therapist, whom she continued seeing after her release from the hospital. A good portion of this part of the novel closely resembles the experiences chronicled by Mary Jane Ward in her autobiographical novel The Snake Pit; Plath later stated that she had seen reviews of The Snake Pit and believed the public wanted to see "mental health stuff," so she deliberately based details of Esther's hospitalization on the procedures and methods outlined in Ward's book. Plath was a patient at McLean Hospital,[19] an upscale facility which resembled the "snake pit" much less than wards in the Metropolitan State Hospital, which may have been where Mary Jane Ward actually was hospitalized.

In a 2006 interview, Joanne Greenberg said that she had been interviewed in 1986 by one of the women who had worked on Mademoiselle with Plath in the college guest editors group. The woman claimed that Plath had put so many details of the students' lives into The Bell Jar that "they could never look at each other again," and that it had caused the breakup of her marriage and possibly others.[20][21]

Janet McCann links Plath's search for feminine independence with a self-described neurotic psychology.[22] Plath's husband has at one point insinuated that The Bell Jar might have been written as a response to many years of electroshock treatment and the scars it left.[23]

Reception

The Bell Jar received "warily positive reviews."[22] The short time span between the publication of the book and Plath's suicide resulted in "few innocent readings" of the novel.[6]

The majority of early readers focused primarily on autobiographical connections from Plath to the protagonist. In response to autobiographical criticism, critic Elizabeth Hardwick urged that readers distinguish between Plath as a writer and Plath as an "event."[6] Robert Scholes, writing for The New York Times, praised the novel's "sharp and uncanny descriptions."[6] Mason Harris of the West Coast Review complimented the novel as using "the 'distorted lens' of madness [to give] an authentic vision of a period which exalted the most oppressive ideal of reason and stability."[6] Howard Moss of The New Yorker gave a mixed review, praising the "black comedy" of the novel, but added that there was "something girlish in its manner [that] betrays the hand of the amateur novelist."[6]

On November 5, 2019, the BBC News listed The Bell Jar on its list of the 100 most inspiring novels.[24]

Legacy and adaptations

The Bell Jar has been referred to many times in popular media. Iris Jamahl Dunkle wrote of the novel that "often, when the novel appears in American films and television series, it stands as a symbol for teenage angst."[3]

Larry Peerce's The Bell Jar (1979) starred Marilyn Hassett as Esther Greenwood, and featured the tagline: "Sometimes just being a woman is an act of courage." In the film, Joan attempts to get Esther to agree to a suicide pact, which does not occur in the book.

In July 2016, it was announced that Kirsten Dunst would be making her directorial debut with an adaptation of The Bell Jar starring Dakota Fanning as Esther Greenwood.[25][26] In August 2019, it was announced Dunst was no longer attached and Bell Jar will become a limited TV series from Showtime.[27]

See also

References

- "Where It All Goes Down". Shmoop.

- McCullough, Frances (1996). "Foreword" to The Bell Jar. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. xii. ISBN 0-06-093018-7.

- Dunkle, Iris Jamahl (2011). "Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar: Understanding Cultural and Historical Context in an Iconic Text". In McCann, Janet (ed.). Critical Insights: The Bell Jar. Pasadena, California: Salem Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-58765-836-5.

- Plath, p. 6

- Steinberg, Peter K. (Summer 2012). "Textual Variations in The Bell Jar Publications". Plath Profiles: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Sylvia Plath Studies. Indiana University. 5: 134–139. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- Smith, Ellen (2011). "Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar: Critical Reception". In Janet McCann (ed.). Critical Insights: The Bell Jar. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. pp. 92–109. ISBN 978-1-58765-836-5.

- Perloff, Marjorie (Autumn 1972). "'A Ritual for Being Born Twice': Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar". Contemporary Literature. University of Wisconsin Press. 13 (4): 507–552. doi:10.2307/1207445. JSTOR 1207445.

- Bonds, Diane (October 1990). "The Separative Self in Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar" (PDF). Women's Studies. Routledge. 18 (1): 49–64. doi:10.1080/00497878.1990.9978819. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Tsank, Stephanie (Summer 2010). "The Bell Jar: A Psychological Case Study". Plath Profiles: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Sylvia Plath Studies. Indiana University. 3.

- MacPherson, Patrick (1990). Reflecting on the Bell Jar. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415043939.

- Butscher, Edward (2003). Sylvia Plath: Method and Madness. Tucson. AZ: Schaffner Press. ISBN 978-0971059825.

- Beck, Aaron (1974). "The Development of Depression: A Cognitive Model". The Psychology of Depression: Contemporary Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Winston-Wiley: 3–27.

- Plath, Sylvia (2005). The Bell Jar. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Tanner, Tony (1971). City of Words: American Fiction 1950-1970. Cambridge University. pp. 262–264. ISBN 978-0060142179.

- Drake, R.E.; Green, A.I.; Mueser, K.T. (2003). "The History of Community Mental Health Treatment and Rehabilitation for Persons with Severe Mental Illness". Community Mental Health Journal. 39. doi:10.1023/A:102586091 (inactive January 22, 2020).

- Budick, E. (December 1987). "The Feminist Discourse of Sylvia Plath's the Bell Jar". College English. 49 (8): 872–885. doi:10.2307/378115. JSTOR 378115.

- Wagner-Martin, Linda; Stevenson, Anne (1996). "Two Views on Sylvia Plath's Life and Career". The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry in English. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192800428.

- Correspondence with Frank O Connor & Seán Ó Faoláin Archived 2007-06-07 at the Wayback Machine, "O'Connor [traveled] to the States to give his famous course on Irish Literature at Harvard (Sylvia Plath was an aspiring student whom he refused a place on his course to)."

- Beam, Alex (2001). Gracefully Insane. New York: PublicAffairs. pp. 151–158. ISBN 978-1-58648-161-2..

- Greenberg, Joanne (April 5, 2006). "'Appearances' in a 'Rose Garden'? Author Joanne Greenberg on her writing, her life, and mental illness" (Radio broadcast). Interviewed by Claudia Cragg. Boulder, Colorado: KGNU. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

I'm gonna tell on her. I shouldn't but I will.

- Wagner-Martin, Linda (1988). Sylvia Plath, the Critical Heritage. New York: Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 0-415-00910-3.

- McCann, Janet (2011). "On the Bell Jar". In Janet McCann (ed.). Critical Insights: The Bell Jar. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-58765-836-5.

- Hughes, Ted (1994). "On Sylvia Plath". Raritan. Rutgers University. 14 (2): 1–10.

-

"100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- Nordine, Michael (July 20, 2016). "'The Bell Jar': Kirsten Dunst Directing, Dakota Fanning Starring". IndieWire. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- McGovern, Joe (July 20, 2016). "Kirsten Dunst to direct 'The Bell Jar' with Dakota Fanning to star". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- Nolfi, Joey (August 16, 2019). "Kirsten Dunst says she's no longer directing The Bell Jar movie adaptation". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

Further reading

- Dowbnia, R. (2014). Consuming Appetites: Food, Sex, and Freedom in Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar. Women's Studies, 43(5), 567–588.

- Susan, C. (2014). Images of Madness and Retrieval: An Exploration of Metaphor in The Bell Jar. (2), 161.

External links

- The Bell Jar at Faded Page (Canada)

- The Bell Jar at Curlie

- A page of Bell Jar book covers

- Faber profile

- The Bell Jar BBC profile

- "Sylvia Plath: The Bell Jar", Salon, October 5, 2000

- "The Bell Jar at 40", Emily Gould, Poetry Foundation

- The Bell Jar at the British Library