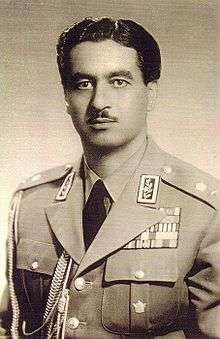

Teymur Bakhtiar

Teymur Bakhtiar (Persian: تیمور بختیار; 1914 – 12 August 1970) was an Iranian general and the founder and head of SAVAK from 1956 to 1961, when he was dismissed by the Shah. In 1970, SAVAK agents assassinated him in Iraq.

Teymur Bakhtiar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1914 Iran |

| Died | July 12, 1970 (aged 55–56) Baghdad, Iraq |

| Buried | Imam Ali Mosque, Najaf, Iraq |

| Service/ | Ground Forces |

| Years of service | 1933–1960 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Commands held | SAVAK |

| Battles/wars | Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran Azerbaijan revolt 1953 Iranian coup d'état |

| Alma mater | Saint-Cyr |

He was an asset in the British military network in Iran.[1][2]

Early life

Bakhtiar was born in 1914 to Sardar Moazzam Bakhtiari, a chieftain of the eminent Bakhtiari tribe. He studied at a French school in Beirut (many Iranians were Francophiles at the time: e. g. Amir Abbas Hoveyda and General Hassan Pakravan) from 1928 to 1933, whereupon he was accepted to the renowned Saint-Cyr military academy.[3] After returning to Iran, he graduated from Tehran's Military Academy.[3] His cousin, Shapour Bakhtiar, and he went together to both Beirut and Paris for higher education.[3]

Then he was made a first lieutenant and dispatched to Zahedan. Bakhtiar's first wife was Iran Khanom, the daughter of the powerful Bakhtiari chieftain Sardar-e Zafar. At that time, the Bakhtiaris were extremely influential; Muhammad Reza Shah's second wife, Soraya Esfandiary Bakhtiari, and the Shah's last prime minister, Shapour Bakhtiar, were both related to Teymour Bakhtiar.

Military career

After the Second World War, when the USSR refused to withdraw its troops from Iran, the separatist movement intensified in a number of regions of the country. In 1946, having received the relevant order of the Shah’s government, Teymur took part in pacifying the Khamseh region. Teymur Bakhtiar organized a kind of guerrilla struggle against soldiers of the Red Army and the separatist movement, as a result of which many separatist fighters were killed in clashes with pro-Shah forces. Suppressing the armed resistance of the nomadic Khamseh tribes, the government sent him as governor to Zahedan (an Iranian city, the administrative center of the Sistan and Baluchestan Province).[4]

Bakhtiar rose rapidly in Iran's military after the fall of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq in 1953. A close associate of Prime Minister Fazlollah Zahedi, he was promoted to military governor of Tehran.[5] One of his first major successes was the capture and trial of Mossadeq's minister of foreign affairs, Hossein Fatemi, who had actively fought the military government that succeeded Mossadegh's period in office.

Bakhtiar waged an extensive campaign against the communist Tudeh party; he arrested and had 24 Tudeh leaders summarily tried and executed, including Khalil Tahmasebi, the assassin of former Prime Minister Ali Razmara. For these accomplishments, he was appointed modern Iran's youngest three-star general in 1954.

From August 1953 to autumn 1954, about 660 of the most ardent supporters of the ousted prime minister were arrested. Of these, 130 were former employees of the oil enterprises in Abadan. A significant part of the arrested officers were members of the Tudeh party. All those who escaped execution were sentenced to various years in prison.[6] On October 19, 1954, the death sentence of the first group of officers from Tudeh was carried out. On October 30, was shot the second group of Tudeh officers consisting of 6 people, on November 8, the third group of 5 people. And on November 10, by the verdict of a military tribunal, Hossein Fatemi was executed. Before being executed, he was brutally tortured.[7] [8] [9]

With the full support of the Shah’s court and the West, the new government brought down brutal repressions against members of the pro-Mossadegh and leftist organizations, figures known for their anti-monarchist views. The government managed to break almost all the military and political resistance of the opposition.[10] Throughout 1953, minor scattered armed protests by opposition representatives against the military government continued. In the spring of 1954, ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani, publicist Seyyed Hossein Makki and other leaders of right-wing nationalists made an attempt to organize mass protests against the Zahedi government. However, the demonstrations that began at their call did not lead to a change in the existing situation.[11] By that time, the court and the government had become masters of the situation, having established full control over the army, police and gendarmerie, strengthening the Shah’s imperial guard.

General Bakhtiar at the head of SAVAK (October 1957 – June 1961)

Bakhtiar was made head of the newly formed intelligence and security service SAVAK in February 1956. He ruthlessly crushed any opposition to the regime, including communists, Islamic fundamentalists, and any other anti-monarchists.

Under the General Bakhtiyar, SAVAK turned into an effective secret agency of internal security to combat the enemies of the monarchical regime of the Pahlavi dynasty.[12]

After Prime Minister Jafar Sharif-Emami was forced to resign in May 1961 due to ongoing demonstrations against large-scale rigging in the parliamentary elections, Teymur Bakhtiar hoped to become the new Prime Minister. Shah made a bet on Ali Amini. General Bakhtiar then contacted the US Embassy in order to enlist their support for a “coup” against Amini. A surprised American ambassador informed the Shah about Bakhtiar’s plans. Soon Bakhtiar was removed from his post as head of SAVAK and was sent abroad.[13]

Fall

With the appointment of Ali Amini as prime minister in 1961, the Shah began to distrust Bakhtiar. Amini warned the Shah of Bakhtiar's contacts with John F. Kennedy, and Bakhtiar was dismissed in 1961. Amini was a Kennedy supporter and was dismissed in 1962 partly because of the Shah's growing distrust of Kennedy.

Initially from his self chosen exile in Geneva, Bakhtiar retaliated by establishing contacts with Iranian dissidents in Europe, Iraq, and Lebanon, using the contacts he had built during his time at SAVAK.

Bakhtiar arrived in Lebanon on April 12, 1968, and was arrested in May for "arms smuggling".[14] Lebanese officials then informed the Iranian embassy in Beirut. As Iranian courts harassed Bakhtiar on charges of high treason, the Iranian government asked the Lebanese government on May 13 to transfer Bakhtiar to Iranian judicial authorities. The Iranian request was based on the principle of cooperation between the judiciary and the Lebanese criminal code regarding extradition of criminals.[15] But Bakhtiar managed to get out of prison and emigrate to Iraq. In 1969, the Iranian parliament passed a law under which Teymur Bakhtiar was deprived of all military ranks, and all his movable and immovable property were confiscated.[16]

He met not only Ayatollah Khomeini but also Reza Radmanesh, the General Secretary of the Tudeh Party, and Mahmud Panahian, the "War Minister" of autonomy-seeking state Azerbaijan People's Government, that had emerged briefly after the Soviet forces withdrew from Iran, following World War II. The Shah issued a warrant for Bakhtiar's arrest, but the general sought refuge in Iraq.

On 12 August 1970, during a hunting party, he was shot and killed by an Iranian Savak agent, feigning to be a sympathizer. As a cover for the plot, the assassin and a colleague had hijacked an Iranian passenger plane, forcing it to land in Baghdad. Disguised as dissidents of the Iranian government, the two assassins duped the Iraqi regime and gained access to Teymur Bakhtiar and his entourage. The truth behind these circumstances emerged only years later. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi himself has been quoted as claiming the assassination a personal success. In an Interview with the acclaimed French author and biographer, Gerard de Villiers, the Shah publicly made a statement to this effect.

After being expelled from the ranks of Tudeh party, Mahmoud Panahian, in May 1970, came to Baghdad, Iraq, by the invitation of former Iraqi government officials. Upon arrival in Baghdad, Mahmoud Panahian had very fruitful discussions with a number of Iranian dissidents, as well as Iranian opposition leaders, namely Morad Aziz Razmavar, as well as Teymur Bakhtiar. Within the next few months, Mahmoud Panahian started recruiting people, organizing anti-Shah radio broadcasts and publishing his lifetime work started in Baku, Azerbaijan: “The Geographical Dictionary of Iranian Nationalities”.

Shortly before Bakhtiar’s assassination, Mahmoud Panahian, received a personal invitation from Bakhtiar to attend the same hunting party, but respectfully declined. Gen. Bahktiar’s would be assassin was a trusted person, living on the premises of Bakhtiar mansion in Baghdad and could have had the General assassinated at a much earlier time. However, the chances for escape were slim, as Teymur Bakhtiar was a VIP guest of the Iraqi government and was both watched and protected by Iraqi bodyguards.

Bakhtiar’s murder was investigated at the highest level. There was only one assassin. Once out hunting in the field, the assassin fired a shot at him from a pistol, hitting him in the shoulder, thus making Bakhtiar drop his rifle. Immediately, Bakhtiar’s Iraqi bodyguard attempted to shoot the assassin with an AK-47, but was shot in the forehead first. The general reached for his revolver with his left hand, but was shot 5 times in the torso and left hand by the assassin. Bakhtiar was taken to a hospital and underwent surgery, but died shortly thereafter from massive internal bleeding.

The assassin quickly left the scene, heading towards the Iranian border. He passed out several kilometers before reaching the border crossing, due to the heat. He was captured by Iraqi border patrol and taken to Baghdad alive. His fate remains unknown. It is also not known where he obtained his small arms training as well as the pistol used.

References

- Abrahamian, Ervand (2013), The Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the roots of modern U.S.–Iranian relations, New York: New Press, The, pp. 151–152, ISBN 978-1-59558-826-5

- Gasiorowski, Mark J. (November 1993), "The Qarani Affair and Iranian Politics", International Journal of Middle East Studies, 25 (4): 625–644, doi:10.1017/S0020743800059298, JSTOR 164538

- "Bakhtiar, Teymour". Bakhtiari Family. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- Milani, Abbas. "Eminent Persians: The Men and Women who Made Modern Iran, 1941-1979", in Two Volumes. (2008), p. 431.

- Gerard de Villiers. "The Imperial Shah: An Informal Biography", Paris, (1974), pp. 308/316.

- Alavi, Nasrin. "We Are Iran". Soft Skull Press. (2005), p. 65. ISBN 1-933368-05-5.

- The New York Times (November 11, 1954); "Ex-Foreign Chief of Iran Executed".

- Ocala Star-Banner (November 10, 1954); "Former foreign executed by firing squad".

- Ehsan Naraghi. "From Palace to Prison: Inside the Iranian Revolution", .I.B. Tauris, (1994), p. 176.

- The Middle East Journal. Middle East Institute., (1954), p. 192.

- Ehsan Naraghi. "From Palace to Prison: Inside the Iranian Revolution", .I.B. Tauris, (1994), p. 176.

- Milani, Abbas. "Eminent Persians: The Men and Women who Made Modern Iran, 1941-1979", in Two Volumes. (2008), p. 433.

- Daily Report, Foreign Radio Broadcasts, Issues 91-95. United States. Central intelligence agency (May 8, 1968).

- United States Central intelligence agency. Daily Report, Foreign Radio Broadcasts, Issues 62-70. (April 1, 1969), N. 62.

- Milani, Abbas. "Eminent Persians: The Men and Women who Made Modern Iran, 1941-1979", in Two Volumes. (2008), p. 434.

Sources

- Gerard de Villiers, "THE IMPERIAL SHAH", Paris, 1974.

- Zabih, S. "Bakhtiar, Teymur." Ed. Ehsan Yarshater. Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation, 1989.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title | Director of the National Organization for Security and Intelligence 1957−1961 |

Succeeded by Hassan Pakravan |