Word painting

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song's lyrics. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

Historical development

Tone painting of words goes at least as far back as Gregorian chant. Little musical patterns are musical words that express not only emotive ideas such as joy but theological meanings as well in the Gregorian. For instance, the pattern FA-MI-SOL-LA signifies the humiliation and death of Christ and His resurrection into glory. FA-MI signifies deprecation, while SOL is the note of the resurrection, and LA is above the resurrection, His heavenly glory ("surrexit Jesus"). Such musical words are placed on words from the Biblical Latin text; for instance when FA-MI-SOL-LA is placed on "et libera" (e.g., introit for Sexagesima Sunday) in the Christian faith it signifies that Christ liberates us from sin through His death and resurrection.

Word painting developed especially in the late 16th century among Italian and English composers of madrigals, to such an extent that word painting devices came to be called madrigalisms. While it originated in secular music, it made its way into other vocal music of the period. While this mannerism is a prominent feature of madrigals of the late 16th century, including both Italian and English, it encountered sharp criticism from some composers. Thomas Campion, writing in the preface to his first book of lute songs 1601, said of it: "... where the nature of everie word is precisely expresst in the Note … such childish observing of words is altogether ridiculous."[1]

Word painting flourished well into the Baroque music period. One famous, well-known example occurs in Handel's Messiah, where a tenor aria contains Handel's setting of the text:

- Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill made low; the crooked straight, and the rough places plain. (Isaiah 40:4)

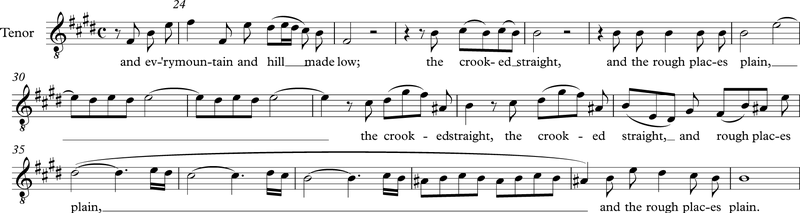

In Handel's melody, the word "valley" ends on a low note, "exalted" is a rising figure; "mountain" forms a peak in the melody, and "hill" a smaller one, while "low" is another low note. "Crooked" is sung to a rapid figure of four different notes, while "straight" is sung on a single note, and in "the rough places plain," "the rough places" is sung over short, separate notes whereas the final word "plain" is extended over several measures in a series of long notes. This can be seen in the following example:

In popular music

A modern example of word painting from the late 20th century occurs in the song "Friends in Low Places" by Garth Brooks. During the chorus, Brooks sings the word "low" on a low note. Similarly, on The Who's album Tommy, the song "Smash the Mirror" contains the line

- Can you hear me? Or do I surmise

- That you feel me? Can you feel my temper

- Rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise....

Each repetition of 'rise' is a semitone higher than the last, making this an especially overt example of word-painting.

"Hallelujah" by Leonard Cohen carries a significant example of the text painting, "It goes like this the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift, the baffled king composing hallelujah.", signifying the movement of the keys and the chord progression, a kind of ambiguous oscillation between moods.

Justin Timberlake's song "What Goes Around" is another popular example of text painting. The lyrics

- What goes around, goes around, goes around

- Comes all the way back around

descend an octave and then return to the upper octave, as though it was going in around in a circle.

In the chorus of "Up Where We Belong", the melody rises during the words "Love lift us up".

In Johnny Cash's "Ring of Fire", there is an inverse word painting where 'down, down, down' is sung to the notes rising, and 'higher' is sung dropping from a higher to a lower note.

In Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's "My Romance," the melody jumps to a higher note on the word "rising" in the line, "My romance doesn't need a castle rising in Spain."

In recordings of George and Ira Gershwin's "They Can't Take That Away from Me," Ella Fitzgerald and others intentionally sing the wrong note on the word "key" in the phrase, "The way you sing off-key."

Another inverse happens during the song "A Spoonful of Sugar" from Mary Poppins, as, during the line "Just a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down," the words "go down" leap from a lower to a higher note.

At the beginning of the first chorus in Luis Fonsi's "Despacito", the music is slowed down when the word "despacito" (slowly) is performed.

In Secret Garden's "You Raise Me Up", the words "you raise me up" are sung in a rising scale at the beginning of the chorus.

Queen use word painting in many of their songs (in particular those written by lead singer Freddie Mercury). In "Somebody to Love", each time the word 'Lord' occurs it is sung as the highest note at the end of an ascending passage. In the same piece, the lyrics 'I've got no rhythm; I just keep losing my beat' fall on off beats to create the impression that he is out of time.

In BTS's "Lie", the whole song is written in minor key to create tensity and dramatic irony. The only lyric that is written in major is "Caught in a lie" which represents the lie of the key signature.[2]

References

- Thomas Campion, First Booke of Ayres (1601), quoted in von Fischer, Grove online

- ReacttotheK (2018-04-12), Classical Musicians React: Jimin 'Lie', retrieved 2018-08-10

Sources

- M. Clement Morin and Robert M. Fowells, "Gregorian Musical Words", in Choral essays: A Tribute to Roger Wagner, edited by Williams Wells Belan, San Carlos (CA): Thomas House Publications, 1993

- Sadie, Stanley. Word Painting. Carter, Tim. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Second edition, vol. 27.

- How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, Part 1, Disc 6, Robert Greenberg, San Francisco Conservatory of Music